Design Principles for Secure Computer Systems

Why Design Principles?

There is an asymmetry in security, the attackers only need to find a single error but you need to prevent many. There are security best practices and design principles to help developers build secure systems.

Security Economics

Security exists outside the digital world. We have assets (i.e. jewelry) we need to protect from threats (i.e. burglars) using defenses (i.e. locks). The asset being secured might be the autonomy of people in a geographic region, in which case there is a military.

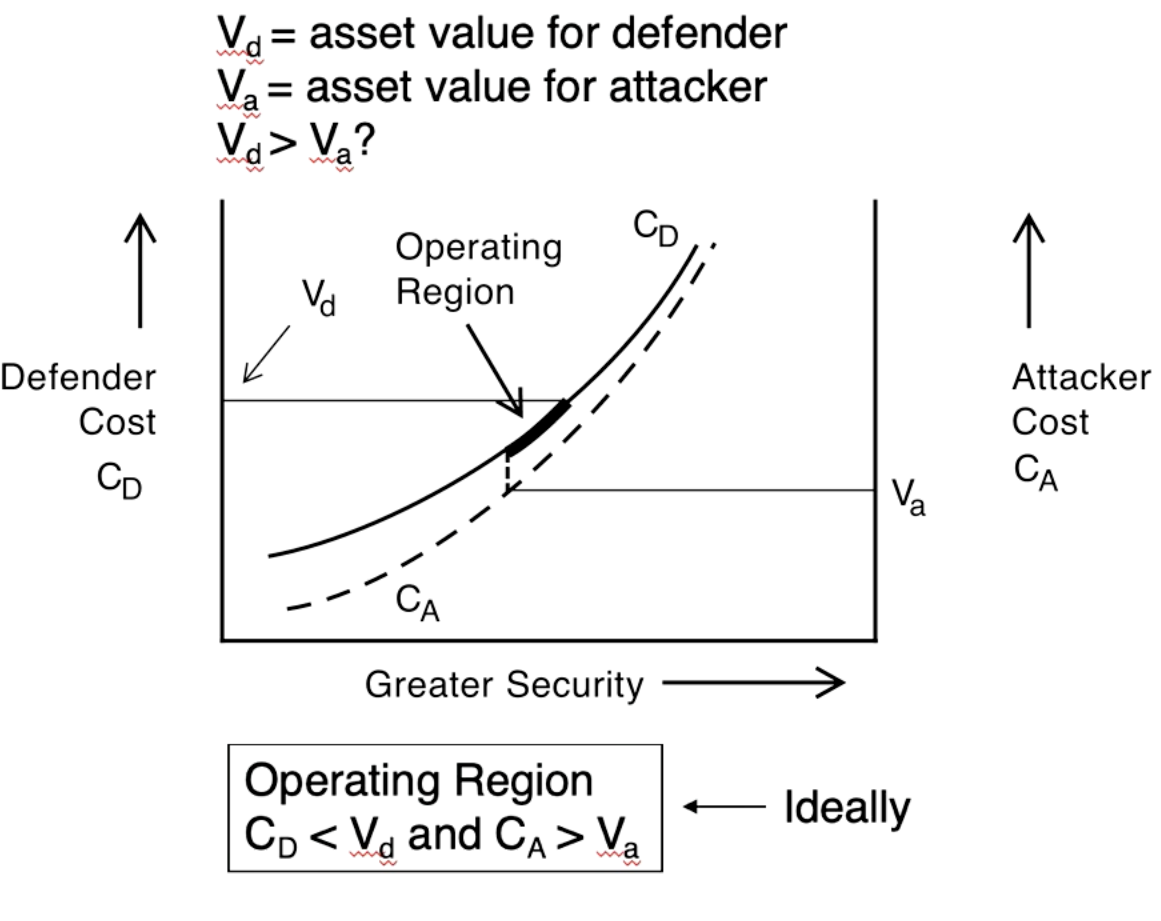

A military is more expensive than a lock and key that keeps jewelry safe. This gets us to the economics of security. We look at what you are securing and how its value relates to your (and your attacker's) budget. This is summarized in the diagram below.

The operating region is where the security makes economic sense for the defender. Too much security (CD > $\text{V}_d$) and we are spending more on security than the secured item is worth. Too little security and ($\text{V}_a$ > CA ), the attacker can make a profit on stealing the thing. The operating region is then when neither of these inequalities hold, as shown in the diagram above.

Cost Benefit Analysis

Cyber risk is defined as $\text{attack likelihood} \times \text{attack impact}$. This is the expected value of the damage done by an attack. We reduce this value to one that we can live with, but this quantity is hard to calculate. There are differing opinions on the likelihood of an attack.

Both defenders and attackers must weigh their costs with what they have to gain by defending/attacking the protected asset.

User Acceptability

Isn't it annoying to do 2-FA all the time now? It is easy to use the same password for all of your accounts, but it really isn't secure. Do you enjoy being forced to update your password from Password101! to Password102!? Security often gets in the way.

People are often the weakest link in a system and a system is only as good as its weakest link. Requiring people to cycle between a series of related passwords might not actually be a good idea from a usability or security perspective. Design systems that users can accept and that have reasonable expectations about user behavior.

Economy of Mechanism

There are tradeoffs between added features and security. With more features there are more ways to attack the system. If you have zero features then there is no product, but perfect security. There is a balance that can be achieved between useful features and security assurances that we can achieve.

Windows 10 is an operating system with about 50 million lines of code. How could that possibly be secure? Later in the course there is discussion of a hypervisor as a TCB instead of the OS itself. A hypervisor is less feature rich and can be implemented in mere hundreds of thousands of lines of code.

Concepts

Economy of mechanism: Have simpler code and features to increase security.

Open design: The attacker should be able to know how the system works and still be unable to execute an attack. The opposite of security by obscurity.

Least Privilege

Background

Users are authenticated (their identity is verified) and are only allowed to perform certain actions. A user doesn't have to be a person, applications are also considered users in the sense that they have their own privileges/permissions.

Think about how you have to give applications permissions to do things like look at your pictures on your phone. What would happen if applications had access to all of your photos by default? That sounds like a privacy/security problem.

Concepts

Least privilege is only giving applications what they need to function.

Separation of Privileges is about having more granular ways of controlling access. It makes sense that an application on your phone can separately request access to your camera and to your microphone.

Fail-safe defaults are about denying access by default. The user has no permissions that are not explicitly granted.

Layered Defense or Defense in Depth

Defense in depth is having multiple diverse protection layers to protect against hackers.

For an example we return to Ken Thompson's Turing Award lecture and discuss a way of protecting ourself from the tricky bug he described.

Obtain two independently developed compilers $A$ and $B$. Assume that at most one has the bug. Let $SA$ and $EA$ be the source and executable for $A$. $SB$ and $EB$ are the source and executable for $B$.

Compile $SA$ with $EA$ to create $X$.

Compile $SA$ with $EB$ to create $Y$.

Compile $SA$ with $X$ to produce $X'$ as well as with $Y$ to produce $Y'$.

If not $X' = Y'$ there is a bug in one of the compilers.

The bug Ken Thompson described turns good source code into a bad executable. We have compiled SA into two different executables using our compilers and check if the executables produce the same output. If they do not produce the same output then one of the compilers made a bad executable from SA.

The defense mechanism described provides an additional layer of security on top of the compiler. You can imagine adding more independent layers for other potential vulnerabilities.

More Thoughts

Do we actually do this?

Do people actually follow these practices? Here are some cautionary tales from people that didn't follow best practices.

The USPS launched a service that let anyone view anyone elses user data, no access control and certainly not least privilege.

Mirai botnet. A botnet that exploits IOT devices with common default username/passwords. Used to DDOS.

The morris worm exploited several different vulnerabilities.

Often design principles are followed. Many enterprises have a firewall as well as an intrusion detection/prevention system. This is defense in layers.

Prevention vs. Cure

In addition to prevention we need detection and response. There are analogous design principles for things like detection.

Don't spam your users with false positive security alerts, else they don't respond to the true positives. This is an example of user acceptability.

Don't just think about prevention. Think about the design principles in the context of detection and response as well.

Last updated