Discretionary Access Control

Motivations

Let's define the authorization problem:

We have a process $P$ making a request $r$ for a protected resource $R$. Authentication tells us the source of the request $r$, a UID is associated with the process $P$ to help determine the source of $R$.

Authorization addresses the question of how to decide if a request $r$ with user id UID should be granted or not.

The Authorization Problem

Security Policies

A security policy should tell us who can access what resources. The security policy can be either discretionary or mandatory. If the creator of a resource defines the security policy for accessing the resource it is called a discretionary access control. In mandatory access control the creator of the policy is not the creator of the resource, it might be the company you work for. This module focuses on discretionary access control.

The TCB has an internal state that helps it make decisions about granting or denying requests.

Access Control Matrix (ACM)

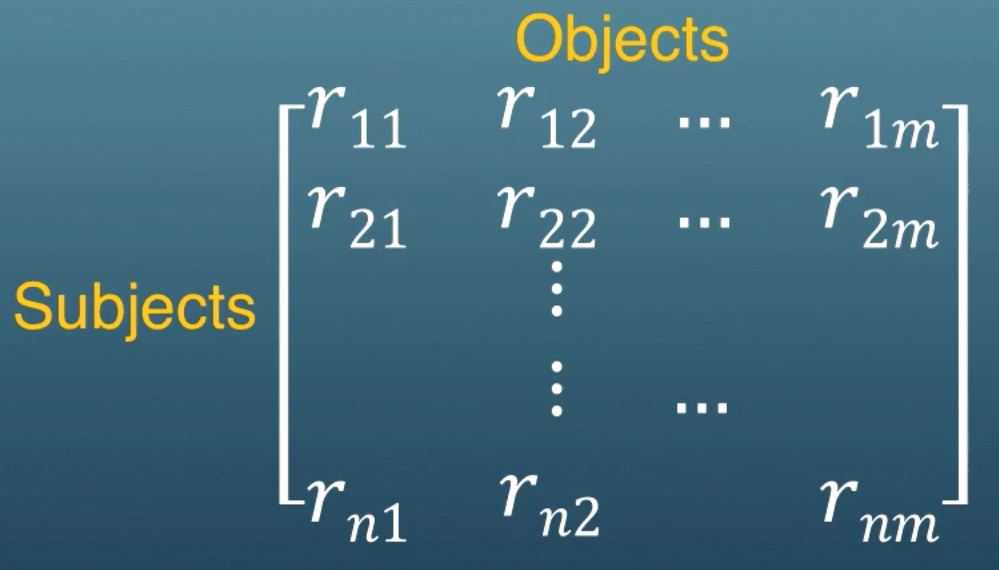

The ACM defines user permissions for resources. In the rows are the subjects/principals. These can be users/groups/roles and are the source of the request. In the columns are objects. These can be files, processes, etc., and are the resources you want to access.

The possible rights that can be granted to a user are the generic access rights. Within each entry of the matrix $r_{ij}$ some subset of these generic access rights is granted to a user $i$ for a resource $j$.

These rights might be read, write, execute for a file. More examples are create, delete, and ownership. There are meta-rights like being able to revoke other user's rights to the object, or being able to give rights (propagation).

The ACM is dynamic. We can have new users coming in, new processes being created. The number of rows and columns changes. The entries in the matrix can change as well.

ACM Operations

To change the ACM you perform operations. Here are some examples.

create(s, f) is where a subject s creates a file f. This will create a new column in the matrix, and set the permission for the entry in the ACM. ACM[s, f] = {own, read, write}.

grant(s, f, read) grants read access for file f to subject s. The owner makes this request (the owner is not s). If the owner runs this command then s will get read permissions, ACM[s, f] = { read }.

Access Right Propagation and The HRU Result

Let r be an access right

r* is the access right when its holder can propagate it

if r* $\in$ ACM[s, o] then r or r* can be granted by s to another subject s'. This means s can grant permissions for s* to either have the role or be able to propagate the role.

r+ is the access right when its holder can revoke it

if r+ $\in$ ACM[s, o] then r or r+ can be deleted by s for a user s' from ACM[s', o]. This means s can revoke permissions for s* to either have the role or be able to revoke the role.

HRU Result

HRU is the initials of the authors. For a given initial state and HRU commands (these are more formal and general than the revoke and grant commands just discussed), does there exist a sequence of commands that results in access right r appearing in a cell of the ACM in which it does not appear in the initial state.

The ability to compute potential future security states in this manner is known as the safety property. The problem of if a given initial state has the safety property is then given.

It turns out that this problem is undecidable. Undecidability is a concept relating to if an algorithm can be constructed to always provide a correct yes/no answer. An example of an undecidable problem is the halting problem, which is worth knowing if you haven't read about it. The authors reduced the problem of computing the safety property to the halting problem, showing that this is undecidable and we cannot construct an algorithm.

ACM Representation and Use

The ACM captures the state that the reference monitor needs to make decisions related to access control.

Many elements of the access control matrix are empty. Least privilege implies most users have access to only a small fraction of the total resources. Only in cells with permissions are non-empty. Matrices where most of the cells are empty are called sparse matrices.

Because the matrix is sparse we don't store the empty entries of the matrix. There are two ways to represent the ACM. Access control lists (ACLs) and capability lists (C-lists).

Access control lists

The ACL belongs to an object and is a list of all users and permissions associated with this object.

This is the non-null entries of the columns of the access control matrix.

When a user references an object the permission is checked by seeing if the user is in the ACL. This is like going to a club and having your name on the list.

Capability lists

The C-list belongs to a user and is a list of all the objects they have permissions for along with what permissions they have.

This is the non-null entries of the user's row in the access control matrix.

A user's reference for the object is allowed if the the user's C-list allows it. This is like having a ticket to the movie theater.

The ACL is stored as metadata for the object and the C-list is stored with the user.

ACL vs. C-lists, Confused Deputy Problem

Overhead of checking permissions: It takes more time to check permissions for the ACL because the TCB has to check if a user is in a list for the object. This means the TCB iterates through a list. With a C-list the user simply has permissions which is more efficient from a time-complexity perspective.

Revocation: To revoke from an ACL we just find the entry in the ACL and delete/modify it. To revoke permissions from a C-list it is more complicated, you have to deal with the user. Discussed in more depth later.

Accountability: Finding all the people that have permissions for an object is east with an ACL, look at the list. With C-lists we need to go through every user to find all the users with permissions for a particular object.

Confused Deputy Problem

Suppose we have a pay-per-user service where we compile files for customers. We have a "billing" file that is updated after each time the service is used. What happens if the customer tries to compile a file and output the compiled file as "billing"?

With ACLs there is not way to stop the corruption of the billing file. With C-lists it is possible.

ACLs

The compile service must have access to the billing file so it can update the information.

The malicious client has to correctly guess the billing file name so it knows where to write to.

When the billing file is accessed the system doesn't know if this is due to the compile service updating the billing file appropriately or if it is due to the compile service's malicious request sent by the user.

C-lists

The client does not have capability for billing.

Case Studies Overview

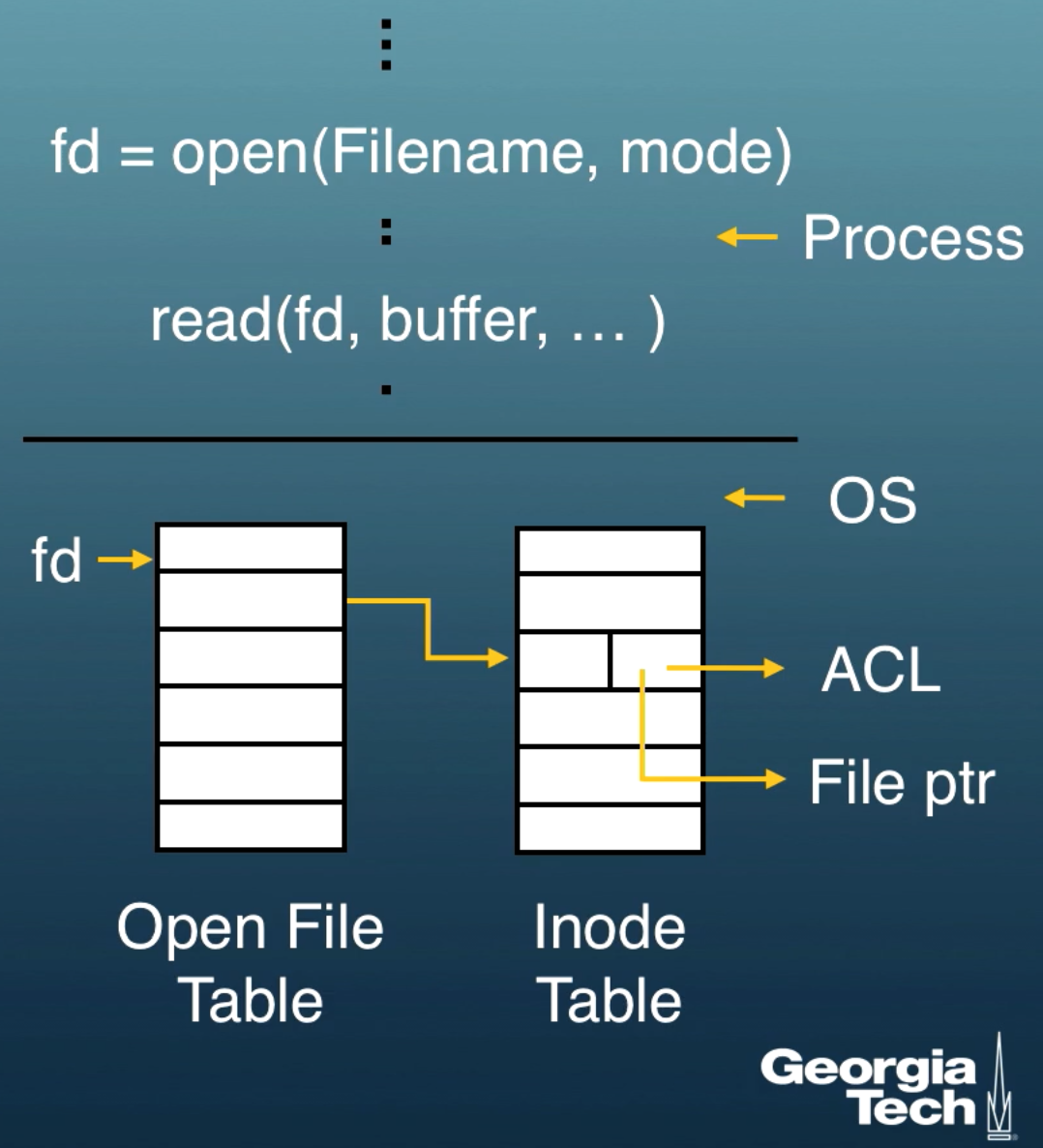

Unix: Has ACLs but for fast access it doesn't check for every read and write.

Windows: Has ACLs with negative access rights.

Java: Protection is finer grain than a process. Based on the code source.

Hydra: Finer grain than processes. Everything is an object and objects are accessed with capabilities.

Unix

Very compact, having a total of 9 bits. Owner, group, and others could have r, w, and x corresponding to read, write, and execute. Using chmod you can set these bits. We don't need a long list of access control entries in the ACL, we just use the 9 bits.

We must open a file before we use it. After the call we get a file descriptor fd. This file descriptor points to the inode table which has a pointer to the file as well as the access control list.

Extending ACLs

Only having 9 bits for access control prevents you from having fine grain access control. There is not enough space for multiple groups and users to have different access control types.

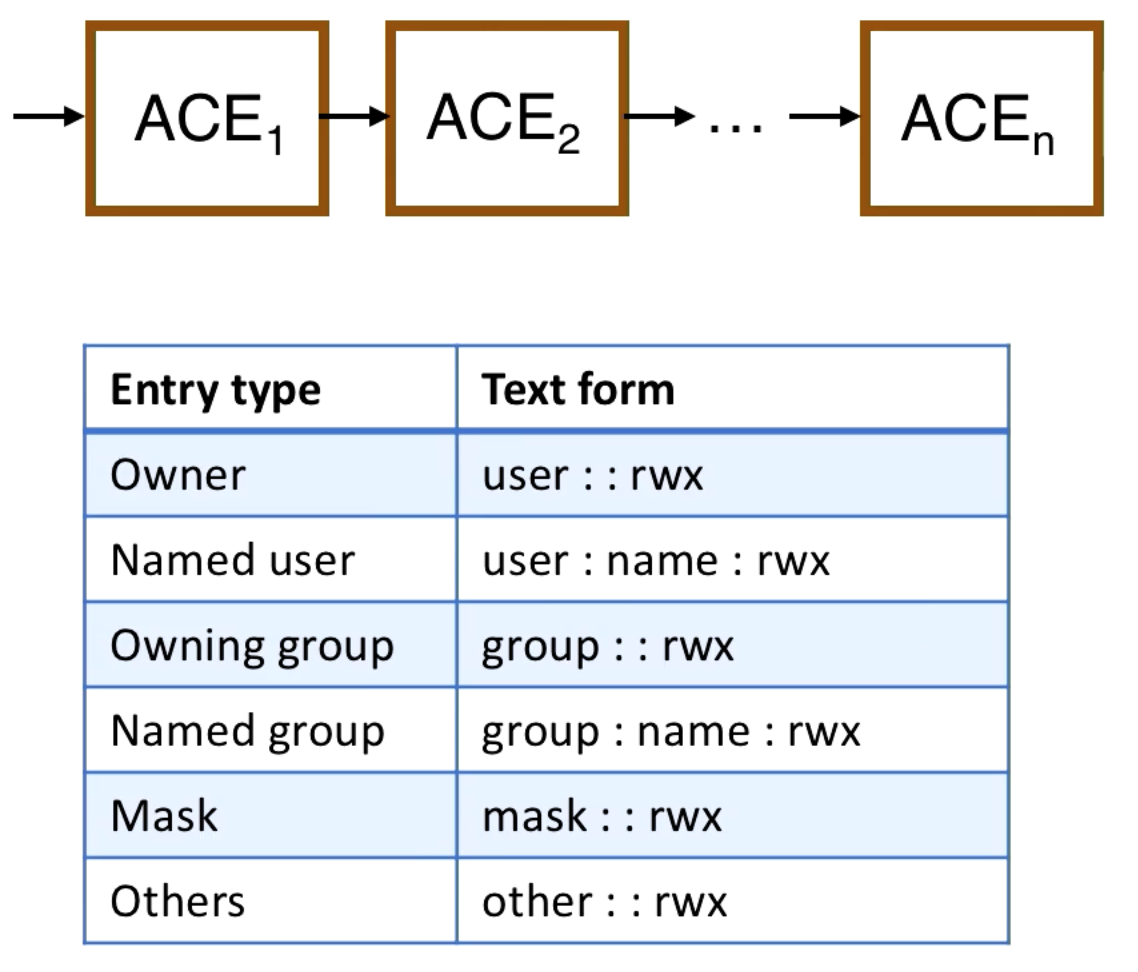

This changes in some UNIX descendents to implement an access control list as a linked list as shown below.

There are different types of access control entries (ACEs) in the ACL. There are entries for the owner and non-owner named users.

You can simplify the ACL by grouping users. There is the owning group and named groups.

There are other users which are not explicitly given in a user or group. We also have masks which let us modify the permissions for all users.

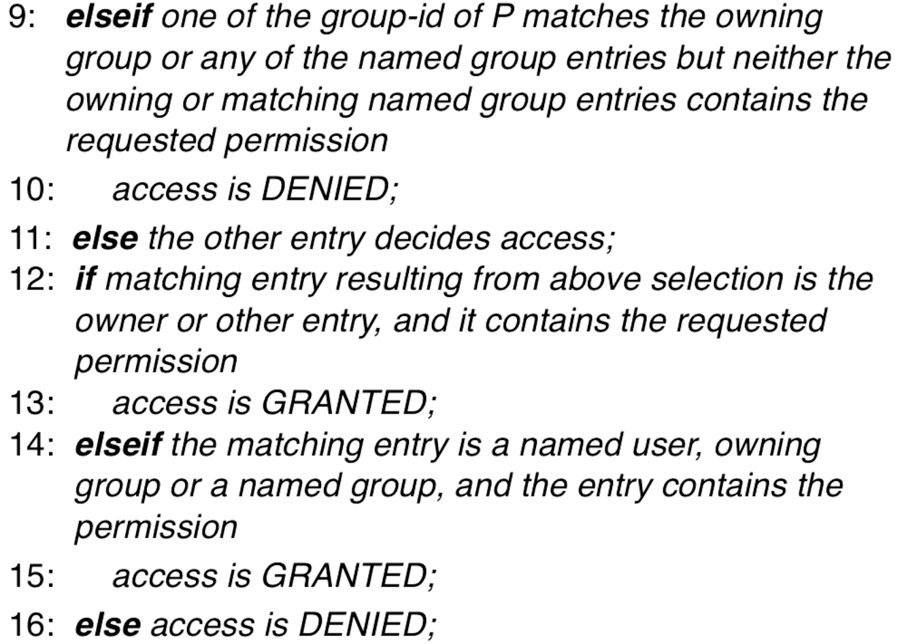

Access Control with Extended ACLs

Setuid() and Access Control

A user U's processes will run with their user-id. If a user wants to update their password, the executable that updates their password in /etc/passwd cannot be run with their user-id, because their user-id doesn't have the right permissions to modify the /etc/passwd file. Executable files can have a setuid bit that lets the user-id change to the owner of the executable file, escalating the priveleges. There is an explicit call setuid() that can be used to modify privileges. There is a setgid bit to set the group ID.

There are different types of user-ids for a process.

Real UID

The owner of the process that is running

Effective UID

UID that is used in access control decisions. If we use setuid() then this will be root.

Saved UID

If we increase privilege but want to go back to lower privilege we can go back to the saved UID.

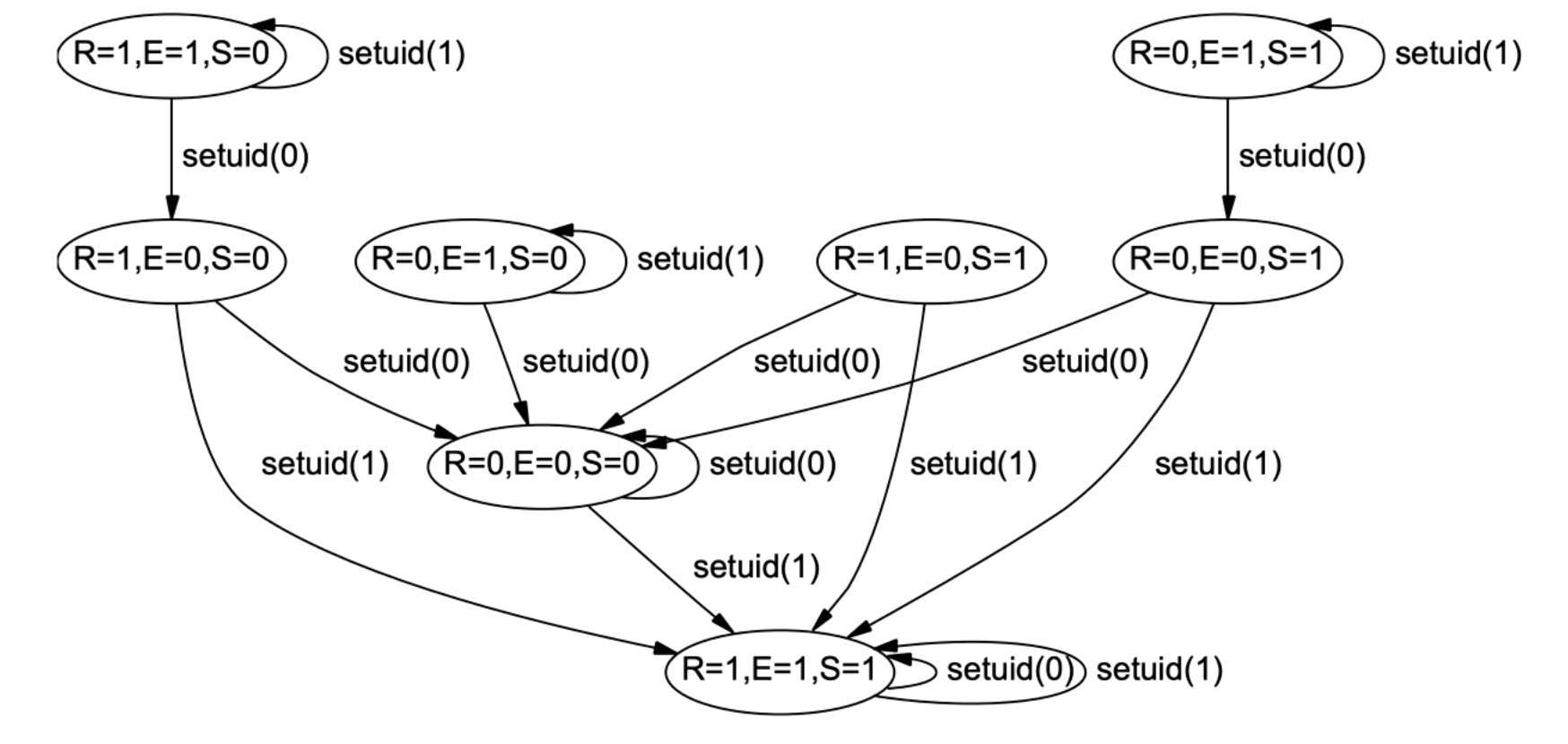

setuid(uid) requires that the UID be equal to the real UID or saved UID when the effective UID is not zero/root.

fork() and exec() calls allow you to create new processes, it will carry over the real UID and effective ID from the forking or executing process.

You can ponder this diagram to understand the behavior of setuid.

Negative Access Rights in Windows

Windows has ACLs similar to the UNIX based systems, but there are ALLOW (positive) and DENY (negative) access control rights.

Access is granted when there is a positive right and there is no negative right. A user can have a positive access right (maybe from a group) and a negative access right (maybe as an individual) at the same time and they will be denied access. We can check negative rights before positive access rights and stop immediately on seeing a negative access right.

Access Control in Java

Java has classes, which instantiate objects, which have methods and byte code run by the JVM. This code can come from anywhere, you might download code and run it on your phone.

Code that is local to your machine vs. code that comes from somewhere else should have different access rights. Untrusted code might have its ability to access the filesystem or internet limited.

Deciding Access in Java

Here is what a policy file looks like in Java. The OS might not see the details of this, but these fine grain permissions are applied by the JVM.

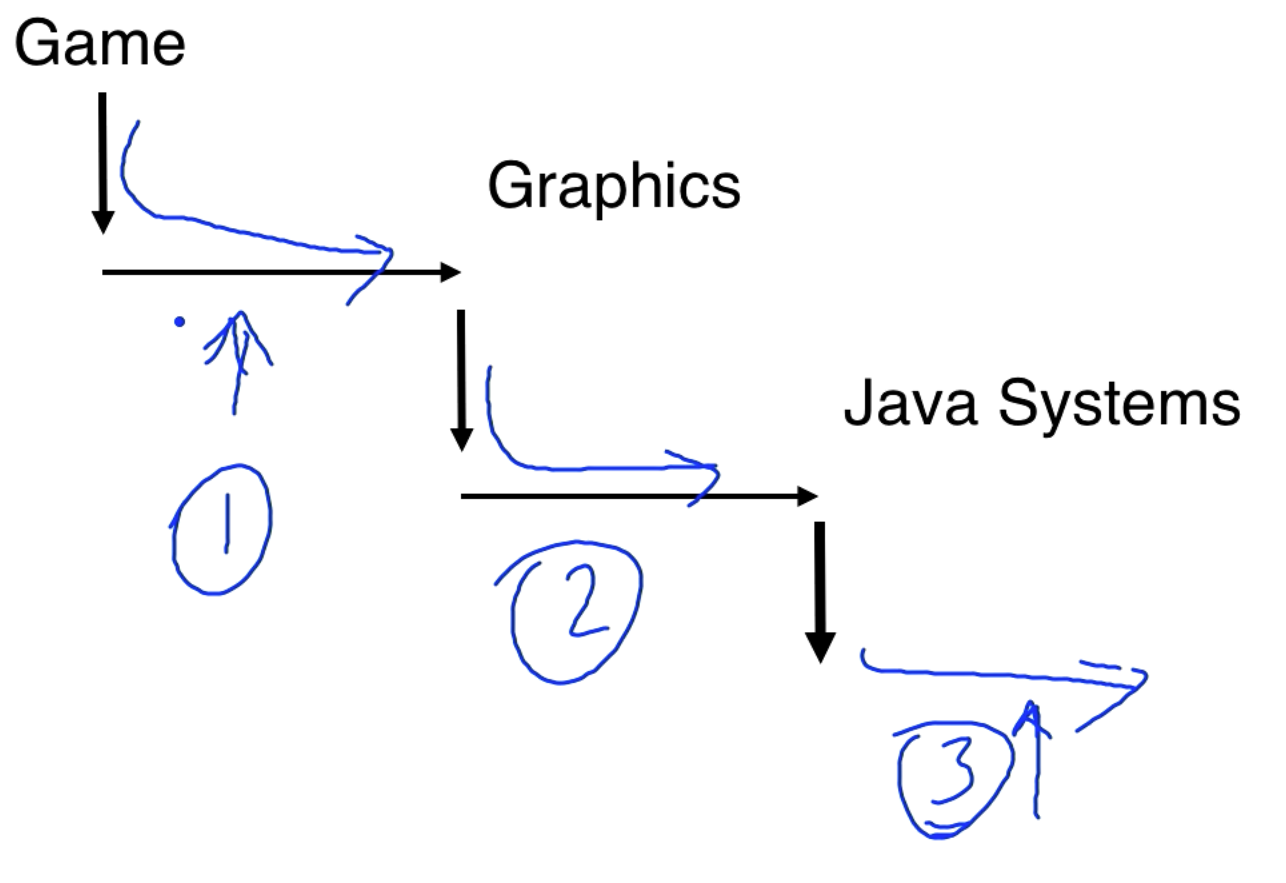

If you have multiple objects in the stack all of the objects in the stack must have access to perform whatever action you are performing. This is called stack introspection. So in the case that our stack has game->graphics->java systems all on the stack, each one of them must give permissions for the actions being performed.

So our access rights are determined by the path we take as well as the policy file.

You can put code inside a doPrivileged block to limit stack introspection. With this we only go back to the doPrivileged in our introspection, as opposed to checking all domains on the stack.

Hydra and C-lists

Hydra is a system that uses C-lists for security.

A capability is an element of a C-list. It is unique, unforgeable, and sharable handle for object O. There was a 64 bit object id + 16 bits of generic rights + 8 bits of auxilliary rights.

The capability for O has associated access rights that define how holder of a capability can access O. The hydra kernel was based on capabilities.

Each call to an object presents a capability to the object which is validated by the kernel.

In Hydra every object has a capability list. While you are in the object you have access to its C-list.

When we go into an object we get new permissions.

Addressing Protection Problems with Capabilities

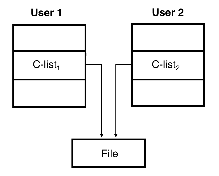

We have two users that want to share a file. When we make a file we got a capability. So both C-lists must have the capability for the file.

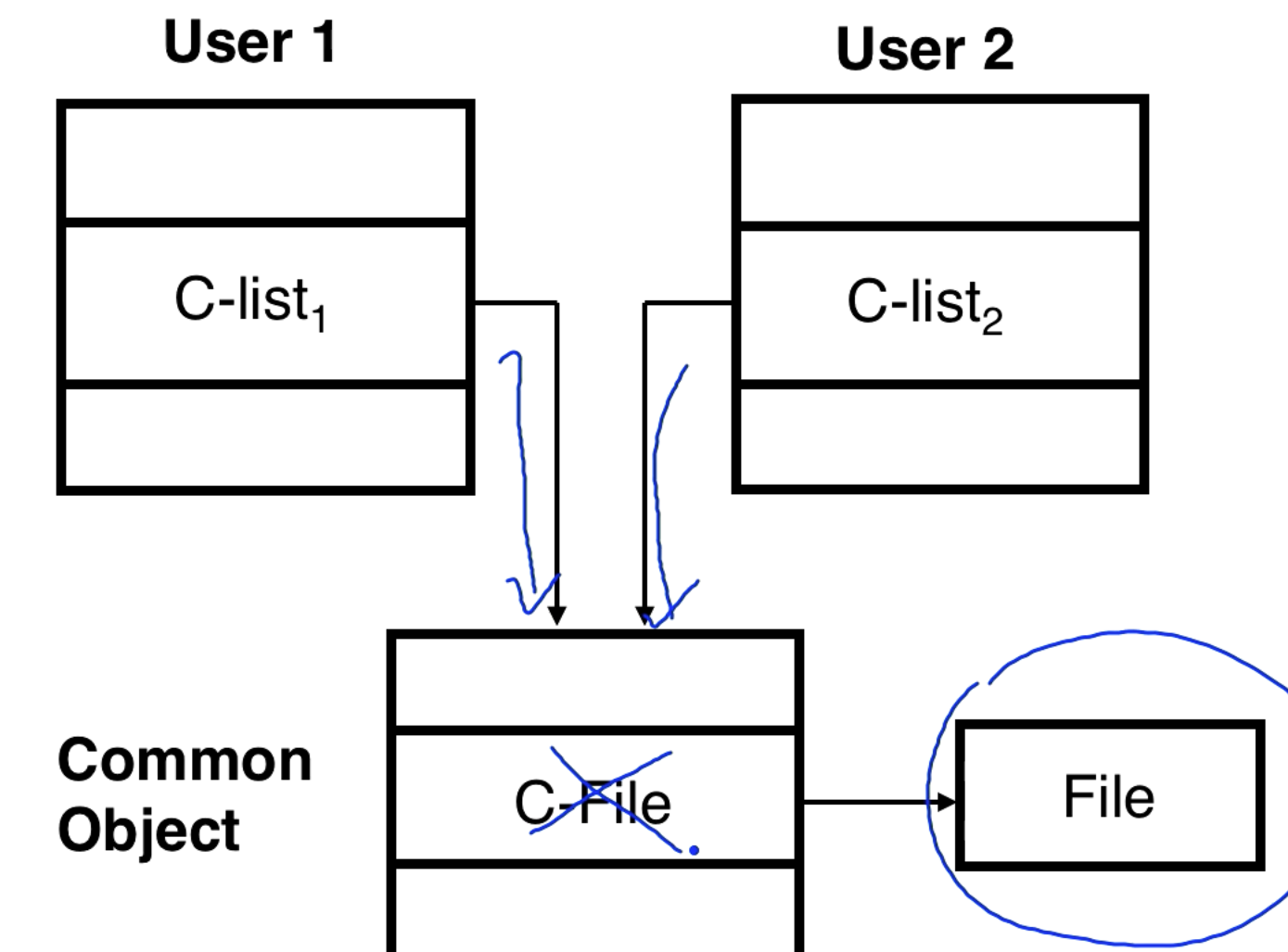

If you want to revoke permissions for users you can't directly remove permissions from the user's C-lists. You can add a layer of indirection and give the users access to a common object which gives them access to the file. To revoke access to the file you revoke access to the common object.

Also, you cannot take a capability from the common object and bring it into your own C-list. There are environment rights which say that a capability can't escape the container it lives in.

Mutual Suspicion Problem

Sometimes two processes need to only share a subset of their capabilities because they don't fully trust each other. This is possible with C-lists and is a solution to the mutual suspicion problem.

Attacks Against Access Control

Linux does access checks when you open a file, and lets you keep the permission until the file is closed or the process is terminated. If someone revokes privileges while the file is open then we do not lose access until the file is closed. Revocation might not be effective for some time. This is the Time of Check, Time of Use (TOCTOU) vulnerability.

Another vulnerability is privilege escalation, a user gets elevated privileges. The national vulnerability database has lots of vulnerabilities related to access controls.

Last updated