Market Mechanics

What Is in an Order

The way that we build a portfolio or, more specifically, buy stocks that we hold in our portfolio, is by issuing orders. We usually send these orders to a stockbroker, and they take care of executing them for us.

There are several components of a well-formed order. First, we need to indicate whether we are looking to buy or sell shares. Second, we need to specify the symbol of the equity that we are interested in - for instance, IBM or SPLV.

Next, we need to indicate how many shares we are interested in transacting. Equities sell in units of shares, not dollars. In other words, we wouldn't tell our broker that we want $100,000 of Apple, but rather 100,000 shares of Apple.

Next, we need to tell the broker whether the order is a market order or a limit order. A market order means that we are willing to accept whatever price the market is currently bearing.

A limit order means that we don't want to do any worse than a specific price. If we are selling stock, a limit order describes the lowest price we would accept for that stock. If we are buying stock, a limit order describes the highest price we are willing to pay for the stock.

If we are issuing a limit order, we must specify the corresponding limit price. If we are issuing a market order, we don't specify a price, as the market determines the price for us.

An order to buy 100 shares of IBM for no more than $99.95 a share might look like this.

An order to sell 150 shares of GOOG at market price might look like this.

The Order Book

Each stock exchange maintains a public order book for each stock that they buy or sell. Investors view the order book to determine how other investors are interested in transacting this stock.

Let's suppose that we issue the very first order of the day: an order to buy 100 shares of IBM at a limit price of $99.95. Since the exchange does not have any shares of IBM for sale at this price, they cannot fulfill our order. Instead, they add it to the order book.

At this point, the order book looks like this:

Let's suppose an order comes in to sell 1000 shares of IBM at a limit price of $100. Since there is no one willing to buy IBM at $100 per share, the exchange has to add this order to its order book as well.

Throughout the day, more and more orders come in, and the order book might look like this.

Suppose the exchange receives a market order to buy 100 shares of IBM. The exchange looks at its order book and determines that, since it has 1600 shares for sale, it can fulfill the order. The exchange must give the client the lowest price, so it sells 100 shares from the pool of 1000 for sale at $100.

As a result, the number of shares for sale at $100 drops, and the order book now looks like this.

Up or Down Quiz

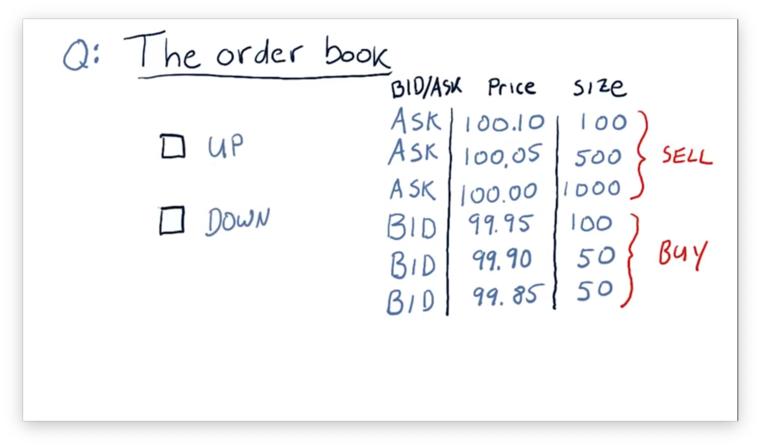

Consider the following order book. Do you think the price of this equity is likely to go up or down in the near future?

Up or Down Quiz Solution

The price is likely to drop in the near future because there is more selling pressure than buying pressure.

Consider what would happen if we put in a market order to sell 200 shares. We would get 100 shares at $99.95, 50 shares at $99.90, and 50 shares at $99.85. Our single order would cause the price of the equity to drop by $0.10.

On the other hand, suppose we issue a market order to buy 200 shares. We would receive 200 of the 1000 shares available for sale at $100. The next market buy order would start with the remaining 800 shares for sale at $100. In other words, our buy order wouldn't affect the sale price at all.

How Orders Affect the Order Book

Consider the following order book for IBM.

What happens if we receive a market order to buy 100 shares of IBM? We have 1000 shares for sale at $100 and, since we have to give the client the best price, we sell them 100 shares at that price. Now we have the following order book.

Let's now consider a limit order for 100 shares of IBM at $100.02. Looking at the order book, we can satisfy that order. Since the client doesn't want to pay more than $100.02 for the shares, we can sell them 100 shares from the pool for sale at $100. Now, our order book looks like this.

Let's look now at a market order to sell 175 shares of IBM. We have 100 shares available at $99.95, so we sell those, but we have to go deeper into the book to fulfill the rest of the order. We sell the block of 50 shares for $99.90, and we sell the remaining 25 shares from the pool of 50 shares priced at $99.85.

Notice that we had to drop the sale price twice in the process of fulfilling the order, which is indicative that our book is experiencing more sell pressure than buy pressure.

After this order, our book looks like this.

Here is a screenshot of a real-life order book.

On the right-hand side, we can see different sell and buy orders and the corresponding execution prices. On the left-hand side, we see a chart depicting the price movement over time as the exchange fulfills these orders.

How Orders Get to the Exchange

We've talked about what orders are and what happens to them when they arrive at the exchange. Let's focus now on the path an order takes from our laptop to an exchange.

Suppose that we have just issued an order from our laptop to buy some stock. The buy order goes over the Internet to the broker, who is, in turn, connected to several exchanges - NYSE, NASDAQ, and BATS, for example.

Our broker has a computer located at each exchange and queries each computer to read the prices from the corresponding order book. The broker gathers all of that information and then routes our order to the exchange that offers the best price: NYSE, in this case.

At any given time, there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions of orders entering exchanges. If the prices differed significantly between exchanges, investors would move their orders to the exchanges that offered more favorable prices.

This act of shifting orders en masse, however, would have the effect of reducing the favorability of the prices on that exchange. As a result, the prices tend not to be very different between exchanges.

Now, let's assume our brokerage has another client, Joe. Joe wants to sell some stock. The brokerage can "match" clients that want to buy with clients who want to sell and fulfill the orders without even going to the exchanges.

Fulfilling the order in-house can be advantageous for the broker since they can avoid paying fees to the exchange to facilitate the order. This process is also safe for the buyer and seller since, according to the law, the brokerage must fulfill their orders with prices that are at least as good as those offered by the exchange.

At the end of the trading day, the brokerage has to register the transaction with one of the exchanges. As a rule of thumb, the brokerage usually records the transaction at the exchange where the particular stock is homed.

Let's consider another example. In this case, Lisa also wants to sell some stock, but she uses a different brokerage firm than us.

Entities called dark pools sit between brokerages and exchanges and pay brokers for the privilege of looking at their orders before they go to the exchanges.

Dark pools are often making predictions about which direction stocks are going to go, so if they see a profitable trade coming from a broker, they will take it.

In this example, Lisa's sell order might be routed from her broker through the dark pool to our broker and connect with our buy order without ever making it to the exchanges.

These days, 80-90% of retail traders' orders never make it to the exchanges; instead, they are either executed internally within a brokerage or filled using a dark pool.

How Hedge Funds Exploit Market Mechanics

Let's suppose that Joe is an investor living in Seattle, and he is currently looking at stock prices on his computer. He thinks that prices are going to go up, so he issues a buy order.

His order travels across the country and, since he is using Etrade as his broker, stops in Atlanta before being routed to the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in New York City.

For each stock, NYSE maintains an order book, which is visible to investors like Joe as well as trading computers colocated in the exchange.

Suppose our hedge fund owns one of these colocated computers. This computer might sit 100 meters from the central exchange computer that holds the order book. Information about the order book travels from the exchange computer to our computer in about 0.3 microseconds.

The distance between the exchange and Joe, on the other hand, is about 2500 miles. As a result, changes in the order book take at least 12 milliseconds to reach Joe, and Joe's subsequent order takes at least 12 milliseconds to reach the exchange.

Our hedge fund is continually observing the order book, and, based on what it sees, it thinks that the price is going to rise. As a result, we buy some stock.

Back in Seattle, Joe is thinking the same thing, so he enters a buy order, which starts making its way across the country. As his order travels, the price begins to rise as a result of the buy orders we submitted.

Eventually, his order reaches the NYSE. By this time, we have already bought the stock and watched the price rise. We then effectively sell the stock at a higher price to "lagging" investors like Joe. We might only hold this stock for a few milliseconds, but we can use this strategy to generate small profits consistently.

Let's look at another type of exploit, which takes advantage of small price differences between exchanges.

Consider two exchanges: one located in New York City and another located in London. Our hedge fund might place a server at each exchange and connect them with an ultra high speed, dedicated connection. The servers continuously monitor the order books at each exchange and compare prices.

Because of the distance between the two exchanges, the prices for a given security might drift slightly. Suppose a difference emerges such that the price in NYC is a little bit lower, and the price in London is a little bit higher.

Our hedge fund will immediately buy shares in New York and sell shares in London. Note that the bought shares and the sold shares don't have to be the same set of shares; instead, we might buy one set and sell another set. The point is that we exploit the difference in prices, a strategy known as arbitrage, to net a small profit.

Because hedge funds monitor the price differences across exchanges all over the world, these sorts of differences are rarely greater than a fraction of a cent. But, such differences do occasionally arise, because there are inefficiencies in the market, and there are hedge funds ready to pick those pennies up off the ground.

Additional Order Types

The exchanges only execute orders across two primary dimensions: buy/sell, and market/limit. There are other types of orders, however, that a broker might implement.

If we want to sell a stock once it dips below a specific price, we might issue a stop-loss order. Similarly, if we want to sell a stock once it surpasses a specific price, we might issue a stop gain order.

A trailing stop order is similar to a stop-loss order, except the threshold price moves. For instance, we might issue a trailing stop at $0.10 behind the price. As the price rises, the value at which we want to sell the stock rises as well. When the price drops more than $0.10, the broker issues a sell order.

These three orders rely on our broker watching the market until the conditions we specify are met and then issuing a simple buy or sell order to an exchange.

Perhaps the most important, impactful kind of order that brokers implement is selling short. Selling short allows us to take a negative position on a stock; in other words, we can borrow stock from a broker and immediately sell it if we believe its price is going to go down.

Mechanics of Short Selling: Entry

Suppose that we want to take a short position in IBM, which is currently selling at $100 per share.

Joe holds 100 shares of IBM, and he likes IBM, so he wants to hold onto the shares long-term. However, he is willing to lend us his 100 shares in the short-term.

Lisa thinks IBM is going to go up in price, so she wants to buy IBM now. We borrow the 100 shares from Joe and sell them to Lisa, who pays us $10,000.

After everything settles, we have $10,000 in our brokerage account, but we also owe Joe 100 shares of IBM. If Joe decides that he wants his shares back, we have to purchase them from the market and return them to him.

Short Selling Quiz

Suppose we've been watching IBM, and we decide to short it when it reaches $100 because we think that it is going to go down. If we short 100 shares at $100 per share and submit an order to buy back the shares at $90 per share to close out our position, what is our net return?

Short Selling Quiz Solution

Each time IBM drops $1 in price, we make $100 because we are shorting 100 shares. Altogether, the stock dropped $10, so we made $1000.

Mechanics of Short Selling: Exit

We now have $10,000 in our account from selling Joe's 100 shares to Lisa at $100 per share, and we owe Joe 100 shares of IBM.

Let's suppose that, since that transaction, IBM has dropped in price and is now selling at $90 per share. We can make a profit from that price differential, so we decide to close our position. To do so, we need to buy 100 shares from someone who wants to sell them, like Nate.

We buy 100 shares from Nate and return them to Joe, thus fulfilling our obligation to Joe. Since IBM was selling at $90 a share, and we owed Joe 100 shares, we had to buy $9000 worth of stock. However, we had $10,000 in our account from our initial sale to Lisa, so we have netted $1000.

In reality, we don't make any agreements with individual investors like Joe, Lisa, or Nate. We make agreements with our broker, who facilitates these types of trades for us.

What Can Go Wrong

Let's suppose we haven't yet closed our short position. We owe 100 shares of IBM, and we need to buy those shares at a price of under $100 per share to make a profit.

If the price of IBM goes up to, say, $150 a share, instead of down to $90 a share, our short becomes unprofitable. When we go to exit our position, it costs us $15,000 to buy back the shares we sold for $10,000, leaving us with a $5,000 loss.

Generally, if we short a stock and the price of that stock goes up instead of down, we lose money. Since the price of a stock can rise without bound, we can potentially lose significant amounts of money.

Last updated