Architecture and Principles

A Brief History of the Internet

ARPANet Late 1960s

ARPANet 1974

Other networks included:

SAT Networks (Satellite)

Packet radio networks

Ethernet local area networks (LANs)

Internet Host Growth

Growth markers include:

DNS (1982)

TCP congestion control (1988)

BGP inter-domain routing (1989)

Streaming media (1992)

World wide web (1993)

Altavista search engine (1995)

P2P applications (2000)

Problems and Growing Pains

One of the major problems is that we are running out of addresses. The current version of the internet protocol - IPv4 - uses 32-bit addresses. This means that the IPv4 internet only has 2^32 (~4B) IP addresses.

Furthermore, IP addresses need to be allocated hierarchically, and many have not been allocated efficiently. For example, MIT has 1/256 of the entire IPv4 address space.

Another problem is congestion control. The goal of congestion control is to match offered load to available capacity. One of the problems with current congestion control algorithms is that they have insufficient dynamic range. They don't work well over slow and flaky wireless links, and they also don't work well over very high speed intercontinental paths.

A third major problem is routing. Routing is the process by which nodes on the internet discover paths to take to reach another destination.

Today's inter-domain routing protocol - BGP - suffers from

no security

easy misconfiguration

poor convergence

non-deterministic behavior

Security is another major problem. While secure practices like encryption and authentication are known, we are not the best when it comes to utilizing secure mechanisms and deploying secure applications.

A fifth problem is denial of service. The internet does a great job at transmitting packets to a destination, even if the destination doesn't want those packets. This makes it easy for an attacker to overload a server. Distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks are common today.

Architectural Design Principles

One of the most important conceptual lessons from the design of the internet is that the design principles and priorities were designed for a certain kind of network. As the internet has evolved, we have begun to feel the growing pains resulting from some of those decisions.

It's not that these design choices were right or wrong. Rather, they reflect the nature of our understanding at the time, as well as the environment and constraints that the designers faced for the particular network that existed at that time.

Some of the technical lessons - for example, packet switching, and fate sharing - from the original design have turned out to be timeless.

Goal

The fundamental design goal of the internet was multiplexed utilization of existing interconnected networks. To achieve multiplexed utilization - shared use of a single communication channel - packet switching was invented. To solve the issue of connecting existing (and future) networks, the "narrow waist" was designed.

Packet Switching

In packet switching, the information for forwarding traffic is contained in the destination address of every datagram, or packet.

Think about how we send letters. All we need to specify on the envelope is the destination address. With that, we can rest assured that the postal network will understand how to route the letter, post office by post office.

In the internet, there is no state established ahead of time, and there are very few assumptions made about the level of service that the network provides: the level of service is often called best effort.

How does packet switching enable sharing? Just as if you were sending a letter, many senders can send over the same network at the same time, effectively sharing the resources in the network.

This is in contrast to the phone network where, if you were to make a phone call, the resources for the path between you and the recipient are dedicated, and are allocated until the phone call ends.

The mode of switching that the conventional phone network uses is called circuit switching, where a signaling protocol sets up the entire path out of band.

An advantage of packet switching is that the sender never gets a busy signal. Packet switching provides the ability to share resources and has better resilience properties. A downside of packet switching is variable delay in message transmission and the potential for packet loss.

In contrast, circuit switching provides resource control, better accounting and reservation of resources, and the ability to pin paths between sender and receiver.

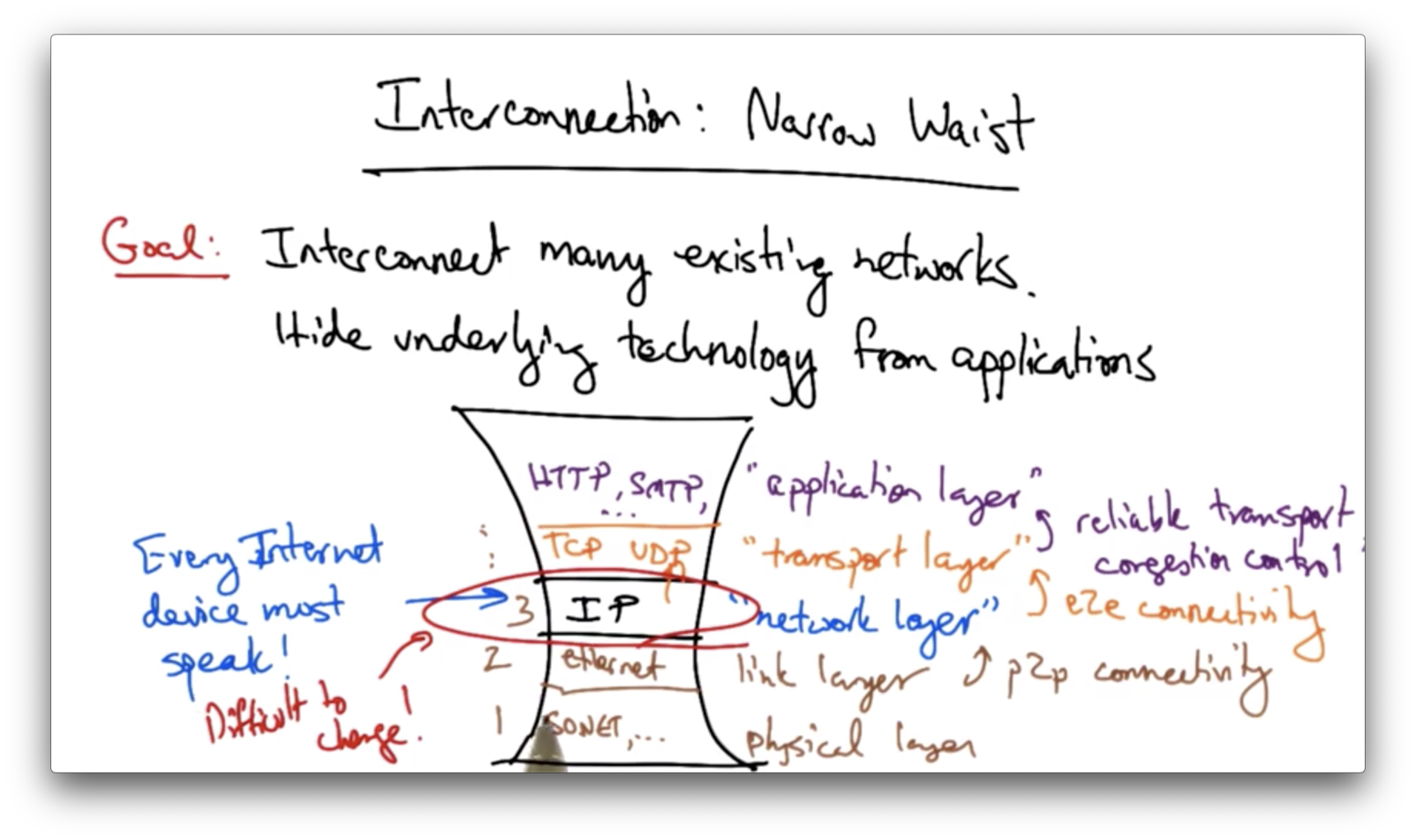

Narrow Waist

The internet architecture has many protocols that are layered on top of one another. At the center is an interconnection protocol called the internet protocol (IP). Every internet device must have an IP stack.

On top of the network layer is the transport layer. The transport layer includes protocols like TCP and UDP. The network layer provides certain guarantees to the transport layer.

One of these guarantees is end-to-end connectivity. The network layer provides a guarantee that a packet destined for a host will be delivered - with best effort - to that host.

On top of the transport layer sits the application layer. The application layer includes many protocols that various internet applications use. For example, the web uses HTTP and mail uses SMTP.

Transport layer protocols provide various guarantees to the application layer, including reliable transport and/or congestion control.

There are protocols below the network layer. The link layer provides point-to-point connectivity, or connectivity on a local area network. A common link layer protocol is ethernet.

Below the link layer, we have the physical layer, which include protocols such as sonnet for optical networks.

The most critical aspect of this design is that the network layer essentially only has one protocol in use, the internet protocol. Every device on the network must speak IP. As long as a device speaks IP, it can get on the internet.

The design is sometimes called "IP over anything" or "anything over IP".

The advantage of the narrow waist is that it is fairly easy to get a device on the network. The drawback is that since every device is running IP, it's very difficult to make any changes at this layer.

Goals Survivability

The network should continue to work even if some of the devices fail.

There are two main ways to achieve survivability: replication and fate sharing.

In replication, one can just keep state at multiple places in the network, so that when any node crashes, there is always a replica waiting to take over.

Fate sharing says that it is acceptable to lose state information for some entity if that entity itself is lost. For example, if a router crashes, all of the state on the router - like the routing tables - is lost.

A system that allows fate sharing and can withstand losing state when losing a device can withstand network failures better and is easier to engineer.

Goals Heterogeneity

The internet supports heterogeneity through the TCP/IP protocol stack.

TCP/IP was designed as a monolithic transport where TCP provided flow control and reliable delivery, and IP provided universal forwarding.

It became clear that every application did not need reliable, in-order delivery. For example, streaming voice/video often perform well even if not every packet is delivered. The domain name system (DNS) often also does not need completely reliable, in-order delivery.

Fortunately, the narrow waist of IP allowed the proliferation of many different transport protocols in addition to TCP.

The internet also supports heterogeneity through the "best effort" service model, whereby the network can lose packets, deliver them out of order, and generally doesn't provide any quality guarantees. The network also doesn't provide information about failures or performance.

Goals Distributed Management

Another goal of the internet is distributed management and there are many scenarios where distributed management has played out.

For example, in addressing, we have routing registries. In North America, the managing organization is called ARIN, while in Europe the same organization is called RIPE. DNS allows each independent organization to manage its own names. BGP allows each independently operated network to configure its own routing policy.

No single entity needs to be in charge, which allows for organic growth and stable management.

On the downside, the internet has no single "owner". In such a network where management is distributed, it can often be very difficult to determine who or what is causing a problem.

Other goals of the internet include:

Cost effectiveness

Ease of attachment

Accountability

The network design is fairly cost effective as is.

Ease of attachment is essentially a huge success. Any device that speaks IP can attach to the internet. The lesson here is that when the barrier to innovation is lowered, people will get creative about the types of devices that will run on top of the internet.

Accountability really wasn't prioritized. Packet-switched networks can make accountability really challenging. Payments and billing for internet usage is much less precise than that for phone network usage.

What's Missing?

Security

Availability

Mobility

Scaling

End to End Argument

The intelligence required to implement a particular application on the communication system should be placed at the endpoints rather than in the middle of the network.

Commonly used examples of the end to end argument include:

error handling in file transfer

end-to-end encryption

TCP/IP split in error handling

Sometimes the end to end argument is summarized as dumb network, intelligent endpoints.

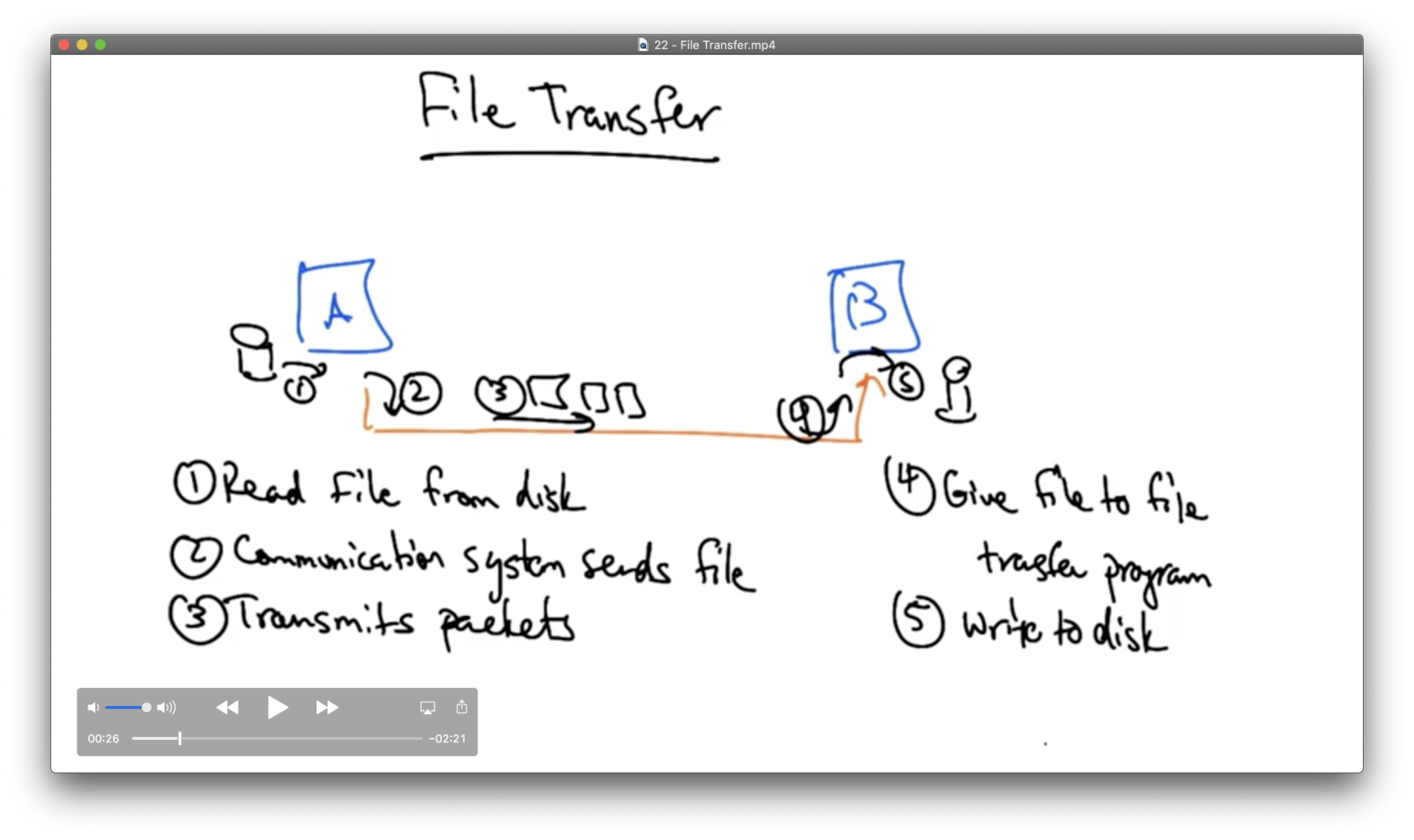

File Transfer

Let's suppose that computer A wants to send a file to computer B.

There can be errors in every single step of this transfer.

It may be possible to introduce means to mitigate errors at the level of the communications channel itself (steps 2-4), but none of those solutions will be complete; that is, they still require application-level checking. Since redundant checks will only add performance overhead, the network ought not to include them.

Another possible solution is to provide some end-to-end error checking. In this case, the application commits or retries based on a checksum of the file.

Another example where the end to end argument applies is encryption. The keys are maintained by the end applications and cipher text is generated before the application sends the message across the network.

What are the "ends"? The "ends" may vary depending on what the application is!

For example, if the application involves internet routing, the ends might be routers. If the application/protocol concerns transport, the ends may be the end hosts.

End to End Argument Violations

There are many things that violate the end to end argument:

NAT

VPN tunnels

TCP splitting

Spam filters

Caches

When considering the end to end argument it's worth asking whether or not the argument is still valid today, and in what cases.

There are questions about what functions belong in the dumb, minimal network. Can we ever add features? It's worth considering whether the end to end argument is constraining innovation of the infrastructure by preventing us from putting some of the more interesting or helpful functions inside the network.

Violation: NAT

A fairly pervasive violation of the end to end argument are home gateways, which typically perform network address translation.

On a home network, we have many devices that need to connect to the network. When we buy service from our ISP, we are typically only given one public IP address.

The idea behind network address translation is that we can give each of our devices a private IP address.

There are regions of the IP address space that are designated for private IPs, such as 192.168.0.0/16.

Each device in the home gets its own private IP address. The public internet sees a public IP address, which is typically the IP address provided by the ISP.

When packets traverse the home router, which is typically running a NAT process, the source address of every packet is re-written to the public IP address.

When traffic comes back to that address, the NAT needs to know which device behind the NAT the traffic needs to be sent to. It uses a mapping of port numbers to identify which device the return traffic should be sent to in the home network.

For outbound traffic the NAT creates a table entry, mapping the device's private IP address and port number to the public IP address, and a different port number, and replaces the non-routable private IP address with the public IP address. It also replaces the sender's source port with a different source port that allows it to demultiplex the packets sent to this return address and port.

For inbound traffic to the network, the NAT checks the destination port on the packet, and based on the port it rewrites the destination IP address and port to the private IP address in the table before forwarding the traffic to a local device in the home network.

The NAT clearly violates the end to end principle because machines behind the NAT are not globally addressable, or routable. Put another way, other hosts on the public internet cannot initiate inbound connections to these devices behind the NAT.

There are protocols to get around this, like the STUN protocol. In these types of protocols, the device sends an initial outbound packet, somewhere, simply to create an entry in the NAT table.

Once that entry has been created, we now have a globally routable address and port to which devices on the public internet can send traffic.

These devices somehow have to learn that public IP address/port that corresponds to that service, which might be done with DNS.

Last updated