Public-Key Cryptography

Modular Arithmetic

Both RSA and Diffie-Hellman - the most widely-used public-key algorithms - are based on number theory and use modular arithmetic - modular addition, multiplication, and exponentiation. Before we dive into the details of the algorithms themselves, let's review the basics of modular arithmetic.

Given a modulus $M$, $x + y \pmod M$ is equal to the remainder of $(x + y) \div M$. For example, $2 + 8 \pmod{10} = 0$, because $10 \div 10$ divides evenly whereas $3 + 8 \pmod {10} = 1$ because $11 \div 10$ yields a remainder of $1$.

In modular addition, a number $k$ has an inverse $k'$ such that $k + k' \pmod M = 0$. For example, for $M = 10$ and $k = 2$, $k' = 8$ because $2 + 8 \pmod{10} = 0$. Every number has an inverse under modular addition.

The presence of an additive inverse means that modular addition is reversible. That is, given $c = a + b \pmod M$, $a = c + b' \pmod M$ and $b = c + a' \pmod M$ . This reversibility is very convenient for encryption because we want the decryption process ideally to be the reverse of the encryption process.

Suppose we have plaintext $p = 3$, key $k = 2$ and encryption algorithm $p + k \pmod{10}$. Thus, ciphertext $c = 3 + 2 \pmod{10} = 5 \pmod{10} = 5$. We can decrypt $c$ using the inverse of $k$: $k'$. Since $k' = 8$, $c + k' \pmod{10} = 5 + 8 \pmod{10} = 13 \pmod{10} = 3 = p$.

Additive Inverse Quiz

Additive Inverse Quiz Solution

In modular addition, a number $k$ has an inverse $k'$ such that $k + k' \pmod M = 0$. In this case, $M = 20$ and $k = 8$. Therefore, $k' = 12$ because $8 + 12 \pmod{20} = 0$.

Modular Multiplication

Given a modulus $M$, $x y \pmod M$ is equal to the remainder of $(x y) \div M$. For example, $5 8 \pmod{10} = 0$, because $40 \div 10$ divides evenly whereas $4 8 \pmod{10} = 2$ because $32 \div 10$ yields a remainder of 2.

In modular multiplication, a number $k$ , has an inverse $k'$ such that $k k' \pmod M = 1$. For example, for $M = 10$ and $k = 3$, $k' = 7$ because $3 7 \pmod{10} = 21 \pmod{10} = 1$.

Not all numbers have multiplicative inverses for a given $M$. For $M = 10$, for example, 2, 5, 6, and 8 do not have multiplicative inverses.

Modular Multiplication Quiz

Modular Multiplication Quiz Solution

In modular multiplication, a number $k$ has an inverse $k'$ such that $k k' \pmod M = 1$. In this case, $M = 17$ and $k = 3$. Therefore, $k' = 6$ because $3 6 \pmod{17} = 18 \pmod{17} = 1$.

Totient Function

Given a modulus $M$, only the numbers that are relatively prime to $M$ have multiplicative inverses in $\pmod M$.

Two numbers $x$ and $y$ are relatively prime to one another if they share no common factor other than 1. For example, 3 and 10 are relatively prime, whereas 2 and 10 - which share 2 as a common factor - are not.

Given $n$, we can calculate how many integers are relatively prime to $n$ using the totient function $\phi(n)$. If $n$ is prime, $\phi(n) = n - 1$, because every number smaller than $n$ is relatively prime to $n$ because $n$ itself is prime. If $n = p q$ and $p$ and $q$ are prime, then $\phi(n) = (p - 1) (q - 1)$. If $n = p q$ and $p$ and $q$ are relatively prime, $\phi(n) = \phi(p) \phi(q)$.

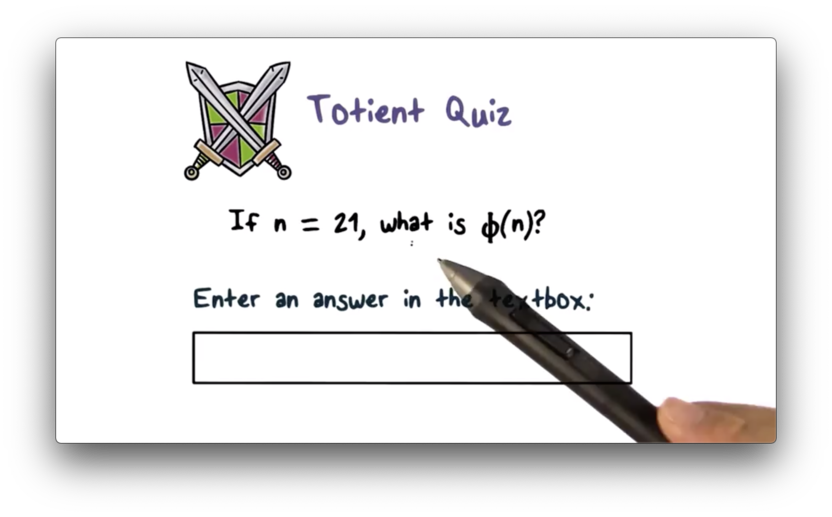

Totient Quiz

Totient Quiz Solution

If $n = p q$ and $p$ and $q$ are prime, then $\phi(n) = (p - 1) (q - 1)$. For $n = 21$, $p = 3$ and $q = 7$, $\phi(n) = (3 - 1) (7 - 1) = 2 6 = 12$.

Modular Exponentiation

In modular exponentiation, $x^y \pmod n = x^{y \pmod{\phi(n)}} \pmod n$. If $y = 1 \pmod{\phi(n)}$, then $x^y \pmod n = x \pmod n$.

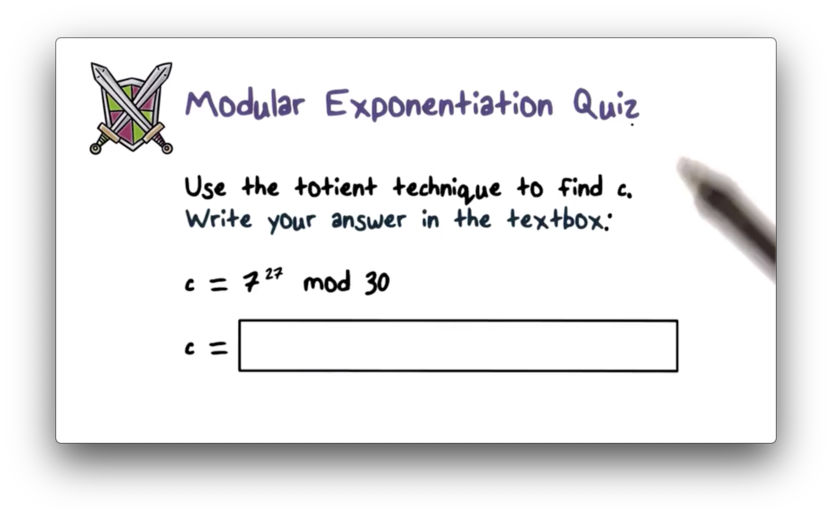

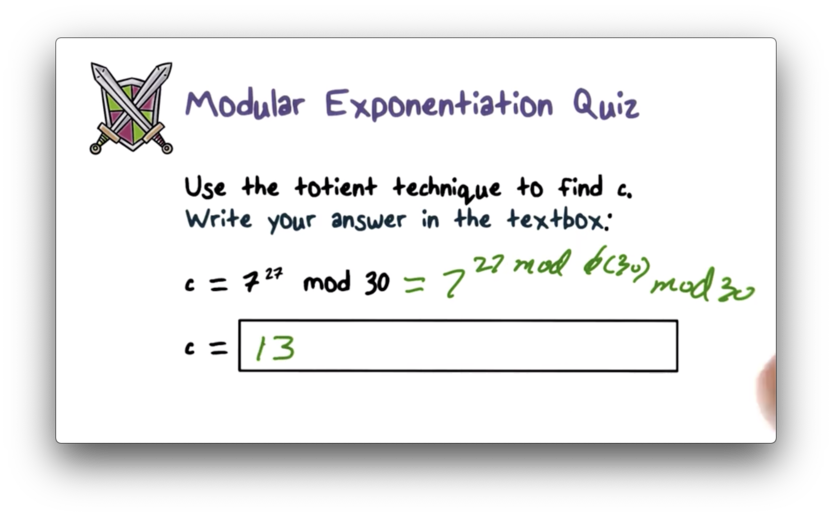

Modular Exponentiation Quiz

Modular Exponentiation Quiz Solution

We know that $x^y \pmod n = x^{y \pmod{\phi(n)}} \pmod n$. For $x = 7$, $y = 27$ and $n = 30$, $7^{27} \pmod{30} = 7^{27 \pmod{\phi(30)}} \pmod{30}$. We can calculate $\phi(30)$ as follows: $\phi(30) = \phi(3) \phi(10) = \phi(3) \phi(2) \phi(5) = 2 1 * 4 = 8$. Thus, $7^{27} \pmod{30} = 7^{27 \pmod 8} \pmod{30}$. If we divide 27 by 8, we are left with a remainder of 3, so $7^{27} \pmod{30} = 7^3 \pmod{30}$. $7^3 = 343$, which yields a remainder of 13 when divided by 30.

RSA (Rivest, Shamir, Adleman)

RSA - named after its three creators - is the most widely used public-key algorithm. RSA supports both public-key encryption and digital signature.

RSA bases the strength of its security on the hypothesis that factoring a massive number into two primes is computationally infeasible problem to solve on a reasonable timescale using modern computers.

RSA supports variable key lengths, and in practice, most people use a 1024-, 2048-, or 4096-bit key. The plaintext block size can also be variable, but the value of the block - represented as a binary integer - must be smaller than the value of the key. The length of the ciphertext block is the same is the key length.

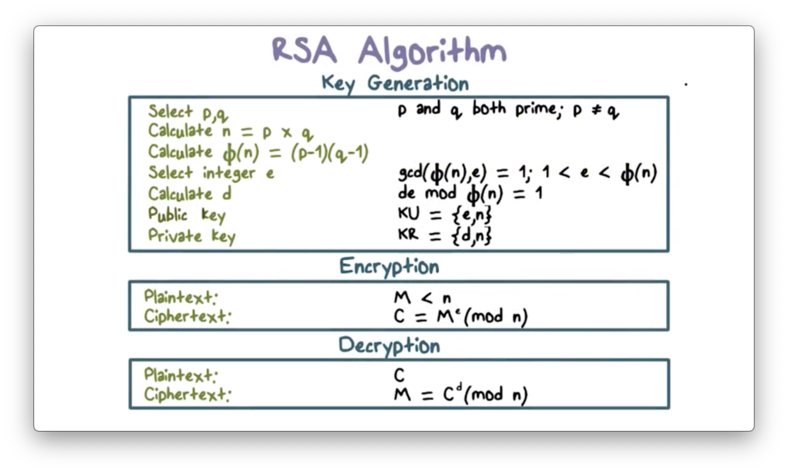

Here is a summary of RSA, including the key generation, encryption, and decryption steps.

The first step is key generation. First, we select two primes $p$ and $q$ that are at least 512 bits in size. Next, we compute $n = p q$, and $\phi(n) = (p - 1) (q - 1)$. Then, we select an integer $e$ that is smaller than $\phi(n)$ and relatively prime to $\phi(n)$. Finally, we calculate $d$: the multiplicative inverse of $e$, $\pmod{\phi(n)}$.

The public key is ${e, n}$. The private key is ${d, n}$.

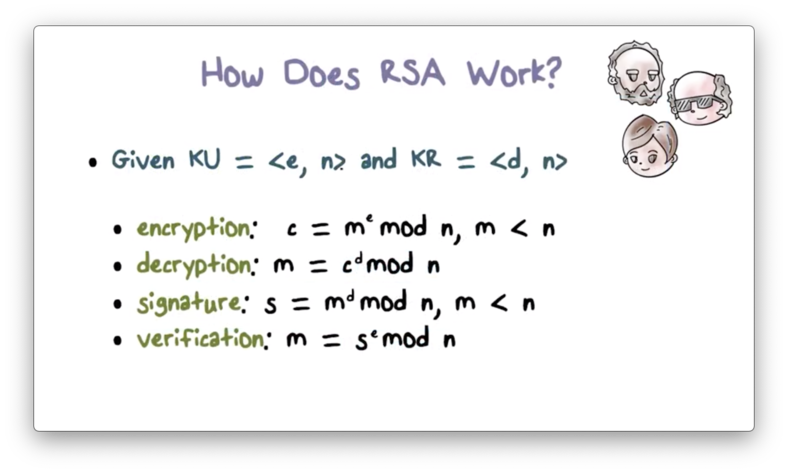

Suppose Bob wishes to send a message $m$ to Alice that only she can read. Bob can encrypt $m$ using Alice's public key, ${e, n}$ by computing $m^e \pmod n$. On receipt of ciphertext $C$, Alice can use her private key, ${d, n}$, and compute $C^d \pmod n$ to recover $m$.

RSA guarantees that only Alice can decrypt $m$ because only she has the private key that pairs with the public key used to encrypt the message.

Digital signature creation and verification work in a similar fashion as encryption and decryption.

To create a signature $s$ for a message $m$, Alice uses her private key, ${d, n}$ to compute $m^d \pmod n$. Bob can verify Alice's signature by using her public key, ${e, n}$ to compute $s^e \pmod n$, which is equivalent to the original message $m$.

Why Does RSA Work

Remember from the rules of modular exponentiation that, for a base $x$, a power $y$, a modulus $n$, $x^y \pmod n = x^{y \pmod{\phi(n)}} \pmod n$. If $y = 1 \pmod{\phi(n)}$, then $x^y \pmod n = x \pmod n$.

Also recall that, for a given public key, ${e, n}$ and its private key ${d, n}$, $d e = 1 \pmod{\phi(n)}$. Thus, $x^{e d} \pmod n = x \pmod n$.

To encrypt a message $m$, we compute $c = m^e \pmod n$. To decrypt $c$, we compute $m = c^d \pmod n$. We can substitute the first expression in for $c$ in the second to get $m = (m^e \pmod n)^d \pmod n$. The right-hand side of the equation simplifies to $m^(ed) \pmod n$, which is equivalent to $m \pmod n$, which equals $m$ since $m < n$.

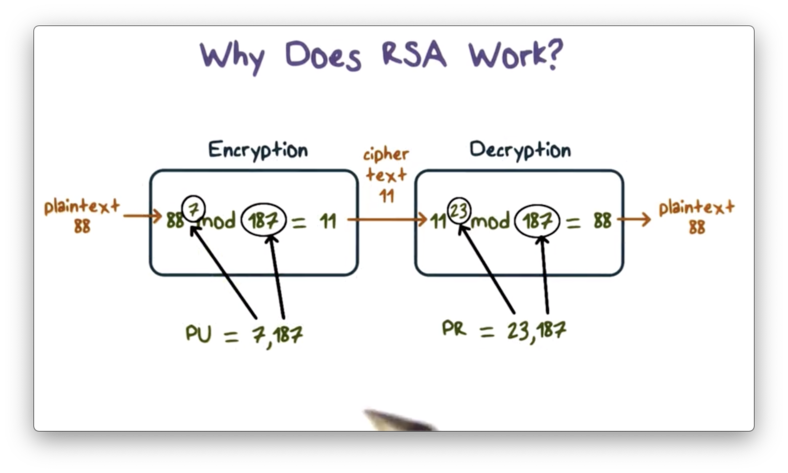

Here is an example of RSA in action.

The key generation step proceeds as follows. First, we select two prime numbers, $p = 17$ and $q = 11$. From these values, we can compute $n$ and $\phi(n)$, as $p q = 187$ and $(p - 1) (q - 1) = 160$, respectively. We select 7 as our public key $e$, as 7 and 160 are relatively prime. The private key is the multiplicative inverse of $e$, $\pmod{\phi(n)}$. The multiplicative inverse of $7 \pmod{160}$ is 23, which is our private key $d$.

To encrypt a plaintext $m = 88$, we compute ciphertext $C = m^e \pmod n = 88^7 \pmod{187} = 11$. To decrypt $C$, we perform $C^d \pmod n = 11^{23} \pmod{187} = 88$, which returns $m$.

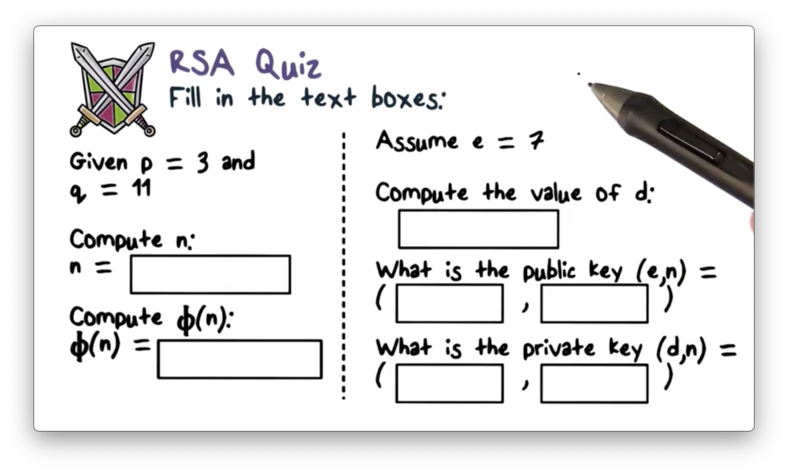

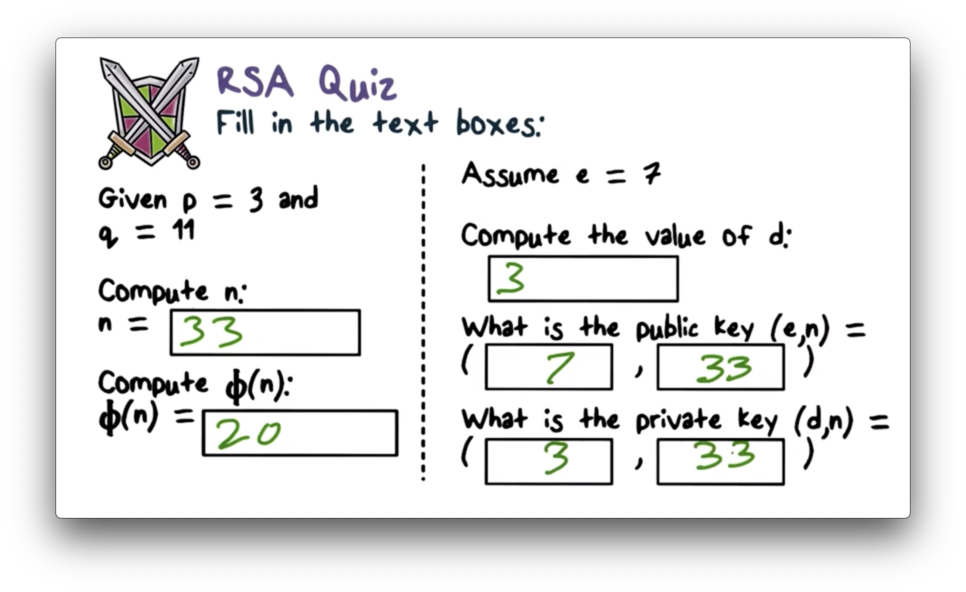

RSA Quiz

RSA Quiz Solution

$n = p q = 11 3 = 33$ and $\phi(n) = (p - 1) (q - 1) = 2 10 = 20$. $e$ and $d$ must be multiplicative inverses $\pmod{\phi(n)}$, so for $e = 7$, $d = 3$, since $21 \pmod{20} = 1$. Finally, public key ${e, n}$ is equal to ${7, 33}$, and private key, ${d, n}$ is equal to ${3, 33}$.

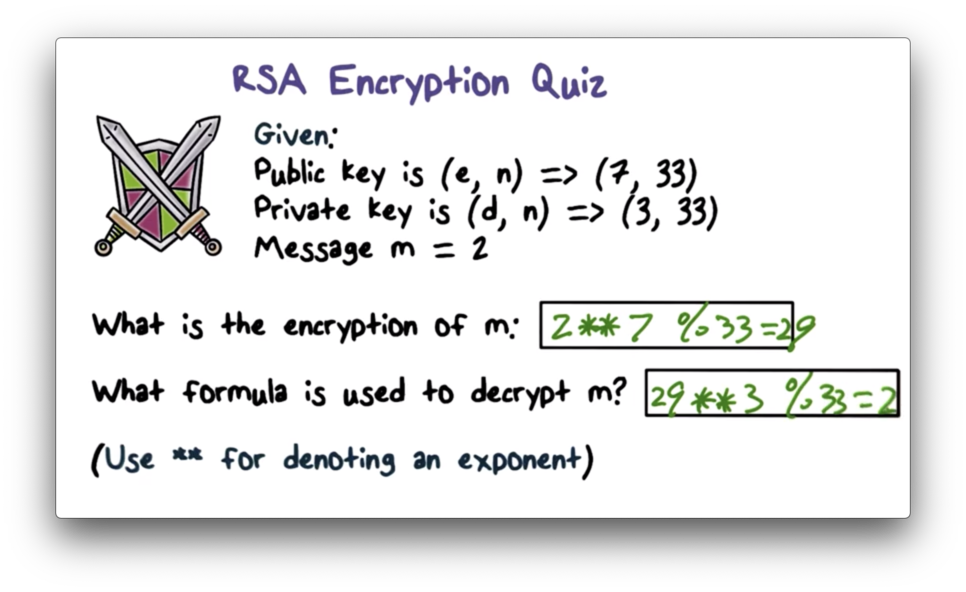

RSA Encryption Quiz

RSA Encryption Quiz Solution

Encrypting message $m$ involves computing $m^e \pmod n$, which is equivalent to $2^7 \pmod{33} = 128 \pmod{33} = 29$. Decrypting ciphertext $C$ involves computing $C^d \pmod n$, which is equivalent to $29^3 \pmod{33} = 24389 \pmod{33} = 3$.

Why is RSA Secure?

RSA bases its security on the hypothesis that factoring a very large number - at least 512 bits, but often in the range of 1024-4096 bits - takes an inordinately long amount of time using modern computers.

If someone finds an efficient way to factor a large number into primes, then the security of RSA is effectively broken. Given public key, ${e, n}$, an efficient factorization of $n$ into $p$ and $q$ allows an attacker to compute $\phi(n)$ and the multiplicative inverse of $e$, $\pmod{\phi(n)}$. This inverse is $d$, the private key.

An attacker can read confidential messages and forge digital signatures against any public key if they can compute a private key in a reasonable amount of time.

Issues with Schoolbook RSA

One issue with RSA is that the algorithm is deterministic. For a given key, the same plaintext message always encrypts to the same ciphertext. Additionally, for specific plaintext values such as 0, 1, or -1, the ciphertext is always equivalent to the plaintext, regardless of the key used.

Another issue is that RSA is malleable. An attacker can induce predictable transformations in plaintext by modifying ciphertext in specific ways.

For example, suppose Bob sends Alice an encrypted message $c = m^e \pmod n$ using Alice's public key, ${e, n}$. The attacker intercepts $c$ and performs the transformation $c' = s^e c$. When Alice receives this ciphertext, the decrypted result is $m' = s m$.

In practice, the standard is to prepend $m$ with padding, a step which addresses the issues described above.

RSA in Practice Quiz

RSA in Practice Quiz Solution

Always use standard libraries, as they have been reviewed and tested by experts in the field.

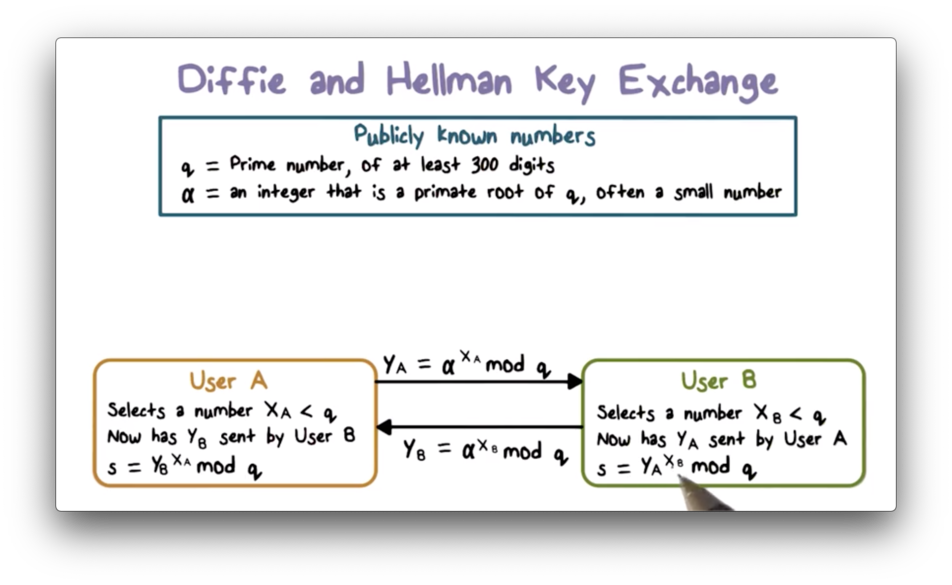

Diffie and Hellman Key Exchange

In the Diffie-Hellman key exchange algorithm, there are two publicly known numbers $q$ and $\alpha$. $q$ is a large prime number - at least 300 digits long - and $\alpha$ is a small primitive root of $q$.

Suppose two users $A$ and $B$ wish to exchange a key using Diffie-Hellman. $A$ selects a random integer $XA < q$ and computes $Y_A = \alpha^{X_A} \pmod q$. Likewise, $B$ selects a random integer $X_B < q$ and then computes $Y_B = \alpha^{X_B} \pmod q$. Each side keeps its $X$ value private and sends their $Y_$ value to the other side.

Upon receiving $Y_B$ from $B$, $A$ computes the key $k = {Y_B}^{X_A} \pmod q$. Similarly, $B$ computes the key $k = {Y_A}^{X_B} \pmod q$ upon receiving $Y_A$ from $A$. The expressions used to compute $k$ by each party are equivalent; that is, ${Y_B}^{X_A} \pmod q = {Y_A}^{X_B} \pmod q$. As a result of this exchange, both sides now share a secret encryption key.

The values of $X_A$ and $X_B$ are private while $\alpha$, $q$, $Y_A$, and $Y_B$ are public. If an attacker $C$ wants to compute the shared key, they must first compute either $X_B$ or $X_A$. The attacker can compute $X_B$, for example, by computing $dlog(\alpha,q)(Y_B)$, where $dlog$ is the discrete logarithm. If $C$ can retrieve $X_B$, they can compute the shared key using $Y_A$ and $q$.

The security of Diffie-Hellman lies in the fact that it is infeasible to compute discrete logarithms for large primes such as $q$ using modern computers.

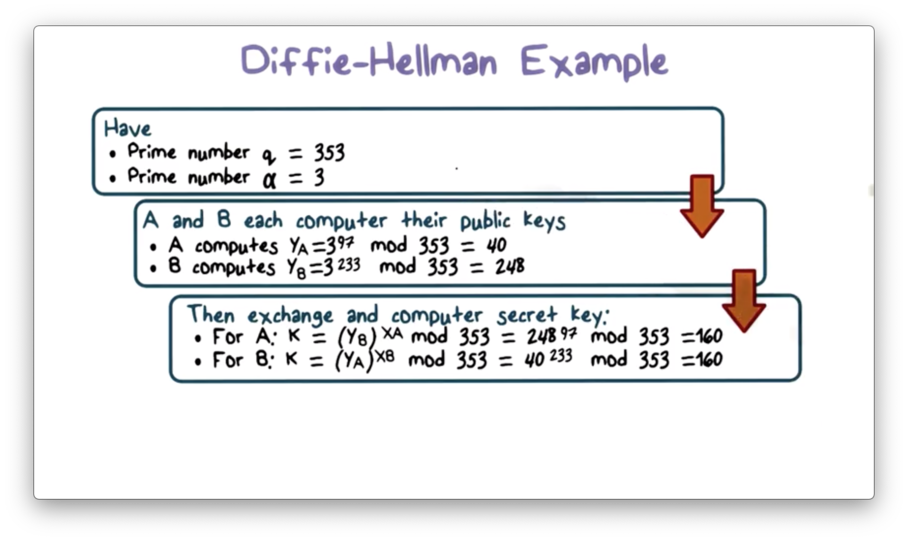

Diffie-Hellman Example

Let's walk through the Diffie-Hellman key exchange using $q = 353$ and $\alpha = 3$.

First, user $A$ selects a random number, $X_A < q = 97$, which they keep secret, and they compute $Y_A = 3^{97} \pmod{353} = 40$. Similarly, user $B$ selects a random number $X_B < q = 233$, which they also keep secret, and they compute $Y_B = 3^{233} \pmod{353} = 248$. Next, $A$ sends 40 to $B$ and $B$ sends 248 to $A$.

Upon receiving $Y_A$, $B$ computes $k = {Y_A}^{X_B} \pmod{353} = 40^{233} \pmod{353} = 160$. Similarly, $A$ computes $k = {Y_B}^{X_A} \pmod{353} = 248^{97} \pmod{353} = 160$. Through this exchange, both $A$ and $B$ have computed the same secret value, which they can now use to encrypt their communications.

We assume that an attacker can access $Y_A$, $Y_B$, $q$, and $\alpha$. Because the numbers in this example are quite small, an attacker can feasibly compute the discrete log to retrieve either $X_B$ or $X_A$. However, as we said before, this computation becomes infeasible for the large values of $q$ used in practice.

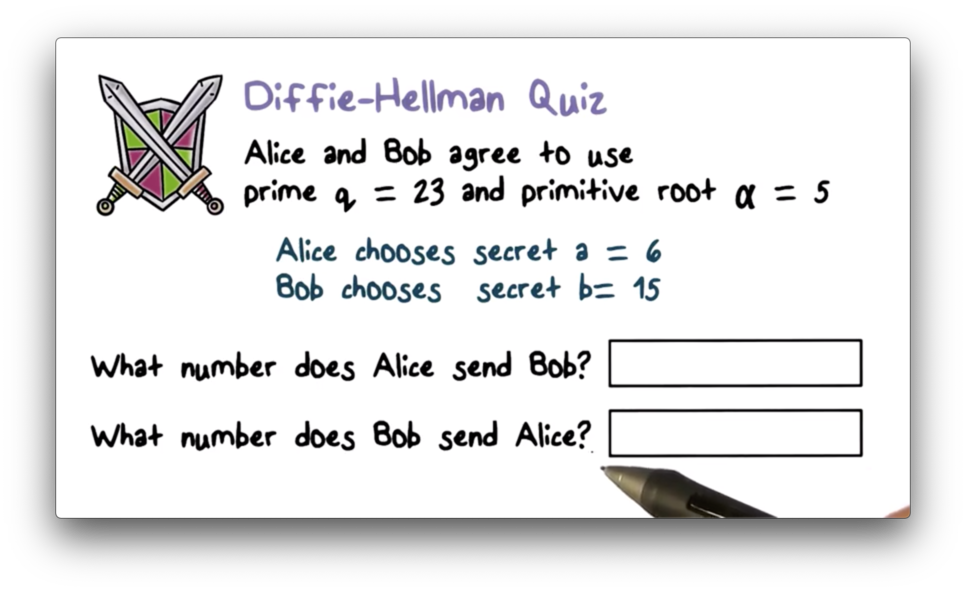

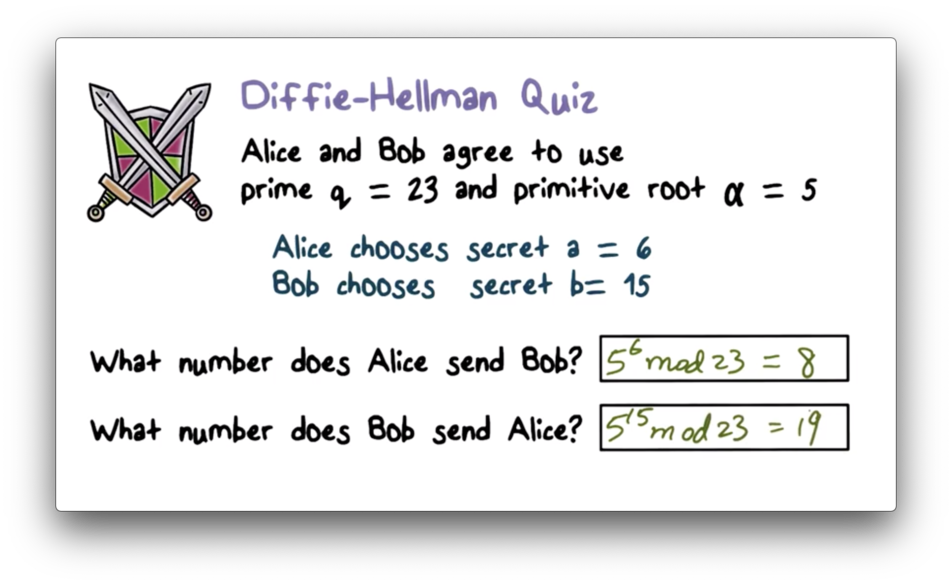

Diffie-Hellman Quiz

Diffie-Hellman Quiz Solution

Alice sends $\alpha^a \pmod q$ to Bob, which is equivalent to $5^6 \pmod{23} = 8$. Bob sends $\alpha^b \pmod q$ to Alice, which is equivalent to $5^{15} \pmod{23} = 19$.

Diffie-Hellman Security

In Diffie-Hellman, neither party ever transmits the shared secret encryption key $S$, nor the locally generated secrets $X_A$ and $X_B$. Since we assume that attackers can intercept any transmitted value, the lack of transmission of secret values adds to the security of the scheme.

We assume that an attacker can access $Y_A$, $Y_B$, $q$, and $\alpha$, since these values are transmitted. The value of local secret $X_A$ is equal to the discrete logarithm $dlog(\alpha,q)(Y_A)$. The security assumption in Diffie-Hellman is that finding the discrete logarithm is infeasible given a very large, prime $q$.

Of course, if this conjecture is not valid, then an adversary knowing $Y_A$, $q$, and $\alpha$ can easily compute $X_A$. With $X_A$ in hand, they can compute $S$ and effectively eavesdrop on communication between $A$ and $B$.

Diffie-Hellman Limitations

Suppose that Alice tells Bob to use Diffie-Hellman. The first thing that Bob has to do is compute $Y_B$ from his local secret $X_B$, and this computation involves a very CPU-intensive exponentiation calculation.

If Alice is a malicious attacker, and Bob is a server, then Alice can request multiple simultaneous Diffie-Hellman sessions with Bob. These requests would cause Bob to waste many CPU cycles on exponentiation, which can result in denial of service.

Additionally, the sole purpose of Diffie-Hellman is key exchange. Unlike RSA, it does not offer encryption and cannot produce digital signatures.

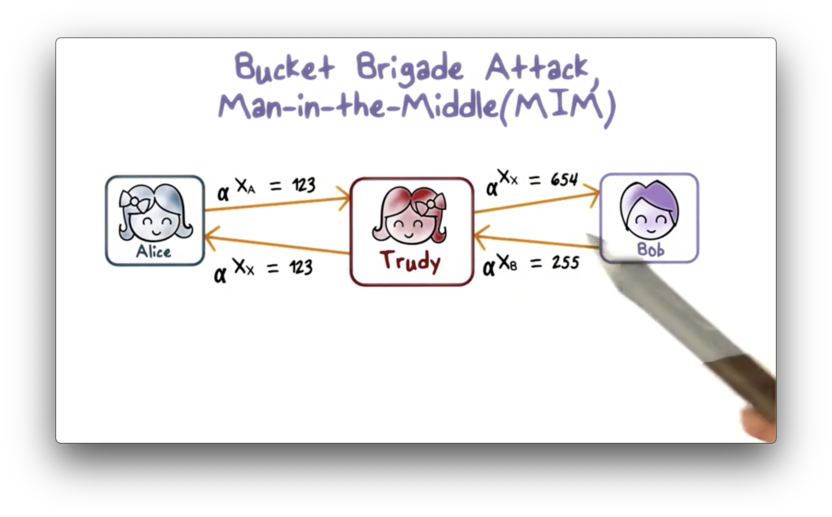

Bucket Brigade Attack, Man in the Middle (MIM)

The biggest threat to the Diffie-Hellman key exchange is the bucket brigade attack, which is a type of man-in-the-middle attack.

In this attack, Trudy intercepts the message $Y_A$ that Alice sends to Bob, and instead sends her own $Y_X$ to Bob, fooling Bob to accept this as $Y_A$. Likewise, Trudy intercepts $Y_B$ that Bob sends to Alice and instead sends her own $Y_X$ to Alice, fooling Alice to believe that $Y_X$ is actually $Y_B$.

The result is that the shared key that Alice computes is the shared key between Alice and Trudy. Similarly, the shared key that Bob computes is the shared key between him and Trudy. In other words, Trudy plays Bob to Alice and Alice to Bob.

This man-in-the-middle attack is possible because the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol does not authenticate Alice or Bob. There is no way for Alice to know that the message that she has received is from Bob, and vice versa.

There are several ways to fix this problem. For example, everyone can publish their public key to a trusted, public repository instead of sending it and risking interception and forgery.

Alternatively, if Alice has already published her RSA public key, she can sign $Y_A$ when she sends it to Bob. Bob can verify that $Y_A$ is really from Alice using her RSA public key.

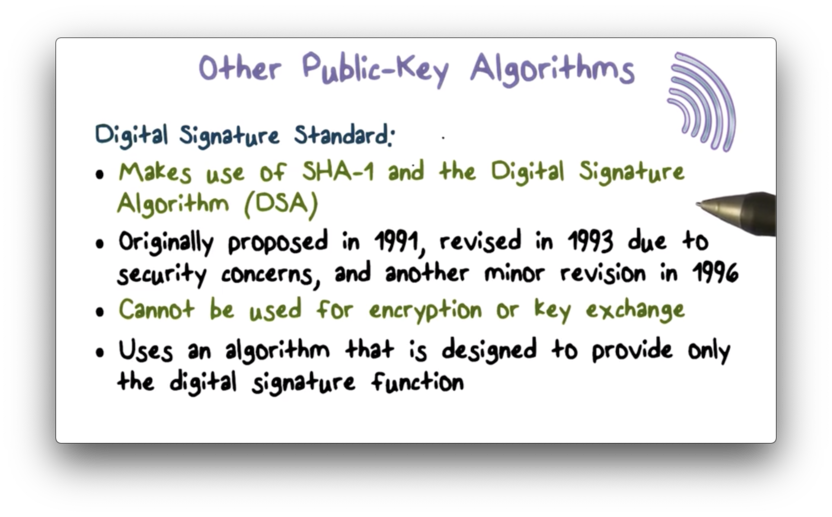

Other Public Key Algorithms

The Digital Signature Standard (DSS) is based on the secure hash function SHA-1. This algorithm is only used for digital signature, not encryption or key exchange.

While RSA is the most widely used public-key algorithm for encryption and digital signature, a competing system known as Elliptic-Curve Cryptography (ECC), has recently begun to challenge RSA. The main advantage of ECC over RSA is that it offers the same security with a far smaller bit size.

On the other hand, RSA has been subject to a lot of cryptanalysis work over the years. For ECC, the cryptanalysis work is still just beginning; therefore, we are not as confident in ECC as we are in RSA.

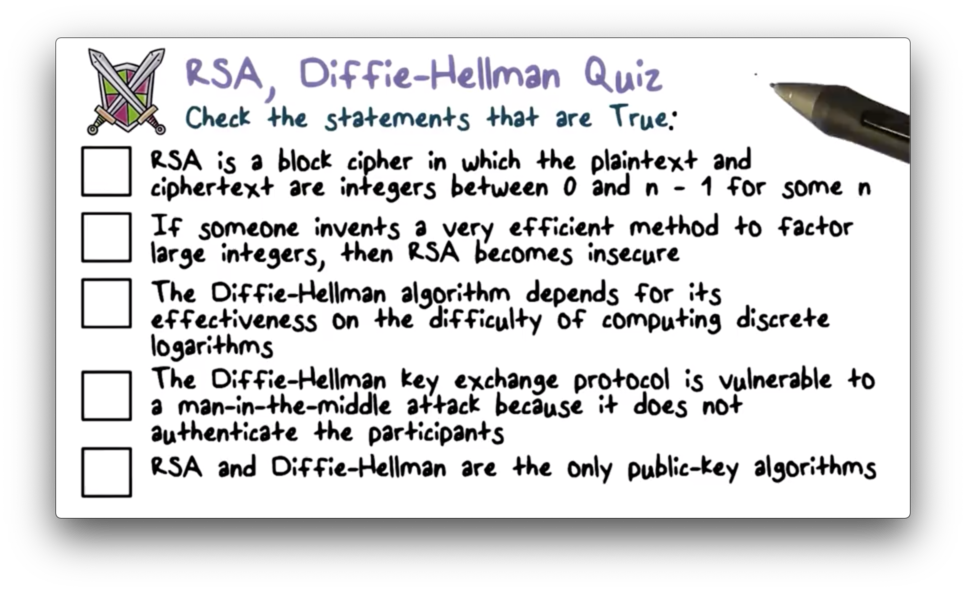

RSA, Diffie-Hellman Quiz

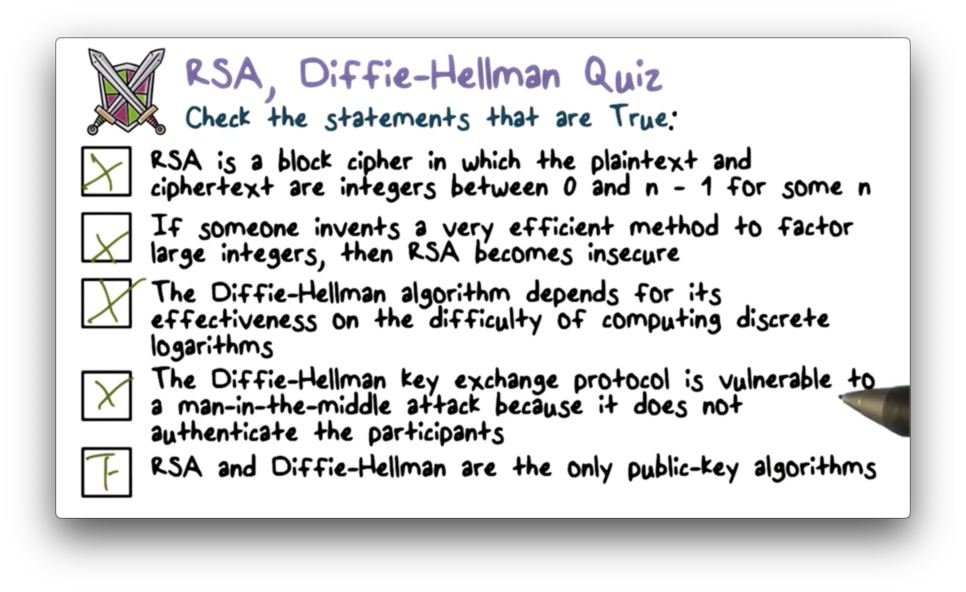

RSA, Diffie-Hellman Quiz Solution

Last updated