Inter-Process Communication

Inter Process Communication

Inter process communication (IPC) refers to a set of mechanisms that the operating system must support in order to permit multiple processes to interact amongst each other. This include mechanisms related to synchronization, coordination and communication.

IPC mechanisms are broadly categorized as either message-based or memory-based. Message-based IPC mechanisms include sockets, pipes, and message queues. Memory-based IPC utilizes shared memory. This may be in the form of unstructured shared physical memory pages or memory mapped files which can be accessed by multiple processes.

Another mechanism that provides higher level semantics with regards to IPC is remote procedure calls (RPC). RPC is more than just a channel for passing information between processes. This method provides some additional detail as to the protocol(s) that will be used, which includes information about the data format and the data exchange procedure.

Finally, the need for communication and coordination illustrates the necessity of synchronization primitives.

Message Based IPC

In messaged-based IPC, processes create messages and then send and receive them. The operating system is responsible for creating and maintaining the channel that is used to send these messages.

The OS provides an interface to the processes so that they can send messages via this channel. The processes send/write messages to a port, and then recv/read messages from a port. The channel is responsible for passing the message from one port to the other.

Since the OS is required to establish the communication and perform each IPC operation, every send and receive call requires a system call and a data copy. When we send, the data must be copied from the process address space into the communication channel. When we receive, the data must be copied from the communication channel into the process address space.

This means that a request-response interaction between two processes requires a total of four user/kernel crossings and four data copying operations. These overheads are one of the negatives of message-based IPC.

One of the positives of this approach is its relative simplicity. The OS kernel will take care of all of the operations regarding channel management and synchronization.

Forms of Message Passing

The are several ways to implement message-based IPC.

Pipes

Pipes are characterized by two endpoints, so only two processes can communicate via a pipe. There is no notion of a message with pipes; instead, there is just a stream of bytes pushed into the pipe from one process and read from the pipe by the other process.

One popular use of pipes is to connect the output from one process to the input of another.

Message Queues

Messages queues understand the notion of messages that they can deliver. A sending process must submit a properly formatted message to the channel, and then the channel can deliver this message to the receiving process.

The OS level functionality regarding message queues includes mechanisms for message priority, custom message scheduling and more.

The use of message queues is supported via different APIs in Unix-based systems. Two common APIs are SysV and POSIX.

Sockets

With sockets, processes send and receive messages through the socket interface. The socket API supports send and recv operations that allow processes to send message buffers in and out of the kernel-level communication buffer.

The socket call itself creates a kernel-level socket buffer. In addition, it will associate any kernel level processing that needs to be associated with the socket along with the actual message movement.

For instance, the socket may be a TCP/IP socket, which means that the entire TCP/IP protocol stack is associated with the socket buffer.

Socket-based communication can happen between processes on different machines! If the process are on different machines, then the communication buffer is really between the process and the network device that will actually send the data.

Shared Memory IPC

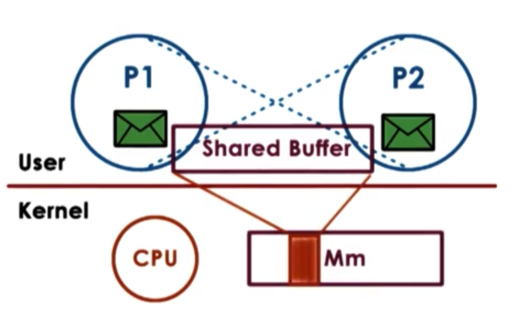

In shared memory IPC, processes read and write into a shared memory region. The operating system is involved in establishing the shared memory channel between the processes. What this means is that the OS will map certain physical pages in memory into the virtual address spaces of both processes. The virtual addresses in each process pointing a shared physical location do not have to be the same. In addition, the shared physical memory section does not need to be contiguous.

The big benefit of this approach is that once the physical memory is mapped into both address spaces, the operating system is out of the way. System calls are used only in the setup phase.

Data copies are reduced, but not necessarily avoided. For data to be available to both process, it needs to explicitly be allocated from the virtual addresses the belong to the shared memory region. If that is not the case, the data within the same address space needs to be copied in and out of the shared memory region.

Since the shared memory area can be concurrently accessed by both processes, this means that processes must explicitly synchronize their shared memory operations. In addition, it is now the developer's responsibility to handle any protocol-related implementations, which adds to the complexity of the application.

Unix-based system support two popular shared memory APIs: SysV and POSIX. In addition, shared memory IPC can be established between processes by using a memory-mapped file.

Copy vs. Map

The goal of both message-based and memory-based IPC is to transfer data from the address space of one process to the address space of another process.

In message-based IPC, this requires that the CPU is involved in copying the data, and CPU cycles are spent every time data is copied to/from ports.

In memory-based IPC, CPU cycles are spent to map physical memory into the address spaces of the processes. The CPU may also be involved in copying the data into the shared address space, but note that there is no user/kernel switching in this case.

The memory-mapping operation is costly, but it is a one time cost, and can pay off even if IPC is performed once. In particular, when we need to move large amounts of data from one address space to another address space, the time it takes to copy - via message-based IPC - greatly exceeds the setup cost of the setup mapping performed in memory-based IPC.

Windows systems leverage this difference. If the data that needs to be transferred is smaller than a certain threshold, the data is copied in and out of a communication channel via a port-like interface. Otherwise the data is mapped into the address space of the target process. This mechanism is called Local Procedure Calls (LPC).

SysV Shared Memory

The operating systems supports segments of shared memory, which don't need to correspond to contiguous physical pages. The operating system treats shared memory as a shared resource using system wide policies. That means that there is a limit on the total number of segments and the total size of the shared memory. Currently in Linux the limit is 4000 segments, although in the past it was as few as 6.

When a process requests that a shared memory segment is created, the operating system allocates the required amount of physical memory and then it assigns to it a unique key. This key is used to uniquely identify the segment within the operating system. Another other process can refer to this segment using this key. If the creating process wants to communicate with other processes using this segment of shared memory, then it needs to make sure that they learn this key somehow.

Using the key, the shared memory segment can be attached by a process. This means that the operating system establishes a valid mapping between the virtual addresses of that process and the physical addresses that back the segment. Multiple processes can attach to the same shared memory segment. Reads and writes to these segments will be visible across all attached processes.

Detaching a segment means invalidating the virtual address mappings for the virtual address region that corresponded to that segment within that process. The page table entries for those virtual addresses will no longer be valid.

A segment is not really destroyed once it is detached. A segment may be attached, detached and re-attached by multiple processes many times through its lifetime.

Once a segment is created, it's essentially a persistent entity until there is an explicit request for it to be destroyed. Note that this is very different from memory that is local to a process, which is reclaimed when the process exits.

SysV Shared Memory API

To create or open a segment we use

We can specify the size of the segment through the size argument, and we can set various flags, like permission flags, with the flag argument.

The shmid is the key that references the shared memory segment. This is not created by the operating system, but rather has to be passed to it by the application. To generate this key, we can use

This function generates a token based on its arguments. If you pass it the same arguments you will always get the same key. It's basically a hashing function. This is how different processes can agree upon how they will obtain a unique key for the memory segment they wish to share.

To attach the shared memory segment into the address space of the process, we can use

The programmer has an option to provide the virtual addresses to which the segment should be mapped, using the addr argument. If NULL is passed, the operating system will choose some suitable addresses.

The returned virtual memory address can be interpreted in various ways, so it is the programmer's responsibility to cast the address to that memory region to the appropriate type.

To detach a segment, we can use

This call invalidates the virtual to physical mappings associated with this shared segment.

Finally, to send commands to the operating system in reference to the shared memory segment we can use

If we specify IPC_RMID as the cmd, we can destroy the segment.

POSIX Shared Memory API

The POSIX shared memory standard doesn't use segments, but rather uses files.

They are not "real" files that live in a filesystem that are used elsewhere by the operating system. Instead they are files that live in the tmpfs filesystem. This filesystem is intended to look and feel like a filesystem, so the operating system can reuse a lot of the mechanisms that it uses for filesystems, but it is really just a bunch of state that is present in physical memory. The OS simply uses the same representation and the same data structures that are used for representing a file to represent a bunch of pages in physical memory that correspond to a share memory region.

Since shared memory segments are now referenced by a file descriptor, there is no longer a need for the key generation process.

A shared memory region can be created/opened with shm_open. To attach shared memory, we can use mmap and to detach shared memory we can use munmap. To destroy a shared memory region, we can call shm_unlink.

Shared Memory and Sync

When data is placed in shared memory, it can be concurrently accessed by all processes that have access to that shared memory region. Therefore, such accesses must be synchronized in order to avoid race conditions. This is the same situation we encountered in multithreaded environments.

There are a couple of options for handling inter-process synchronization. We can rely on the mechanisms supported by the threading libraries that can be used within processes. For example, two pthreads processes can synchronize amongst each other using pthreads mutexes and condition variables. In addition, the OS itself supports certain mechanisms for synchronization that are available for IPC.

Regardless of the method that is chosen, there must be mechanisms available to coordinate the number of concurrent accesses to shared segments (think mutexes) and to coordinate communicating when data is available or ready for consumption in the shared memory segment (think condition variables and signals).

PThreads Sync for IPC

One of the attributes that are used to specify the properties of the mutex or the condition variable when they are created is whether or not that synchronization variable is private to a process or shared amongst processes.

The keyword for this is PTHREAD_PROCESS_SHARED. If we specify this in the attribute structs that are passed to mutex/condition variable initialization we will ensure that our synchronization variables will be visible across processes.

One very important thing to remember is that these data structures must also live in shared memory!

To create the shared memory segment, we first need to create our segment identifier. We do this with ftok, passing arg[0] which is the pathname for the program executable as well as some integer parameter. We pass this id into shmget, where we specify a segment size of 1KB and also pass in some flags.

Using the segment id, we attach the segment with shmat, which returns a shared memory address - which we assign to shm_address here. shm_address is the virtual address in this process's address space that points to the physically shared memory.

Then we cast that address to the datatype of the struct we defined - shm_data_struct_t. This struct has two fields. One field is the actual buffer of information, the data. The other component is the mutex. In this example, the mutex will control access to the data.

To actually create the mutex, we first have to create the mutexattr struct. Once we create this struct, we can set the pshared attribute with PTHREAD_PROCESS_SHARED. Then we initialize the mutex with that data structure, using the pointer to the mutex inside the struct that lives in the shared memory region.

This set of operations will properly allocate and initialize a mutex that is shared amongst processes.

Sync for Other IPC

In addition, shared memory accesses can be synchronized using operating system provided mechanisms for inter-process interactions. This is particularly important because the PTHREAD_PROCESS_SHARED option for pthreads isn't necessarily always supported on every platform.

We can rely on other means of synchronization in those cases, such as message queues and semaphores.

With message queues, we can implement mutual exclusion via send/recv operations. For example, process A can write to the data in shared memory and then send a "ready" message into the queue. Process B can receive the msg, read the data, and send an "ok" message back.

Semaphores are an OS support synchronization construct and a binary semaphore can have two states, 0 or 1. When a semaphore has a value of 0, the process will be blocked. If the semaphore has a value of 1, the process will decrement the value (to 0) and will proceed.

IPC Command Line Tools

Design Considerations

Let's consider two multithreaded processes in which the threads need to communicate via shared memory.

First, consider how many segments the processes will need to communicate.

Will you use one large segment? If so, you will have to implement some kind of management of the shared memory. You will need some manager that will be responsible for allocating and freeing memory in this region.

Alternatively, you can have multiple segments, one for each pairwise communication. If you choose this strategy, it is probably a smart idea to pre-allocate a pool of segments ahead of time, so you don't need to incur the cost of creating a segment in the middle of execution. With this strategy, you will also need to manage how these segments are picked up for use by the pairs. A queue of segment ids is probably sufficient.

Second, you will need to think about how large your segments should be.

If the size of the data is known up front (and is static), you can just make all your segments that size. Typically an operating system will have a limit on the maximum segment size, so this strategy only works in very restricted cases.

If you want to support arbitrary messages sizes that are potentially much larger than the segment size, one option is to transfer the data in rounds. The sending process sends the message in chunks, and the receiving process reads in those chunks and saves them somewhere until the entire message is received. In this case, the programmer will need to include some protocol to track the progress of the data movement through the shared memory region.

Last updated