Memory Management

Memory Management: Goals

Remember that one of the roles of the operating system is to manage the physical resources - in this case DRAM - on behalf of one or more executing processes.

The operating system provides an address space to an executing process as a way from decoupling the physical memory from the memory that a process interacts with. Almost everything uses virtual addresses, and the operating system translates these address into physical addresses where the actual data is stored.

The range of the virtual addresses that are visible to a process can be much larger than the actual amount of physical memory behind the scenes. In order to manage the physical memory, the operating system must be able to allocate physical memory and also arbitrate how it is being accessed.

Allocation requires that the operating system incorporate certain mechanisms and data structures so that it can track how memory is used and what memory is free. In addition, since the physical memory is smaller than the virtual memory, it is possible that some of the virtual memory locations are not present in physical memory and may reference some secondary storage, like disk. The operating system must be able to replace the contents in physical memory with contents from disk.

Arbitration requires that the operating system can quickly interpret and verify a process memory access. The OS should quickly be able to translate a virtual address into a physical address and validate it to verify that it is a legal access. Modern operating systems rely on a combination of hardware support and software implementations to accomplish this.

The virtual address space is subdivided into fixed-size segments called pages. The physical memory is divided into page frames of the same size. In terms of allocation, the operating system maps pages into page frames. In this type of page-based memory management the arbitration is done via page tables.

Paging is not the only way to decouple the virtual and physical memories. Another approach is segmentation, or a segment-based memory approach. With segmentation, the allocation process doesn't use fixed-size pages, but rather more flexibly-sized segments that can be mapped to some regions in physical memory as well as swapped in and out of physical memory. Arbitration of accesses uses segment registers that are typical supported on modern hardware.

Paging is the dominant memory management mechanism used in modern operating systems.

Memory Management: Hardware Support

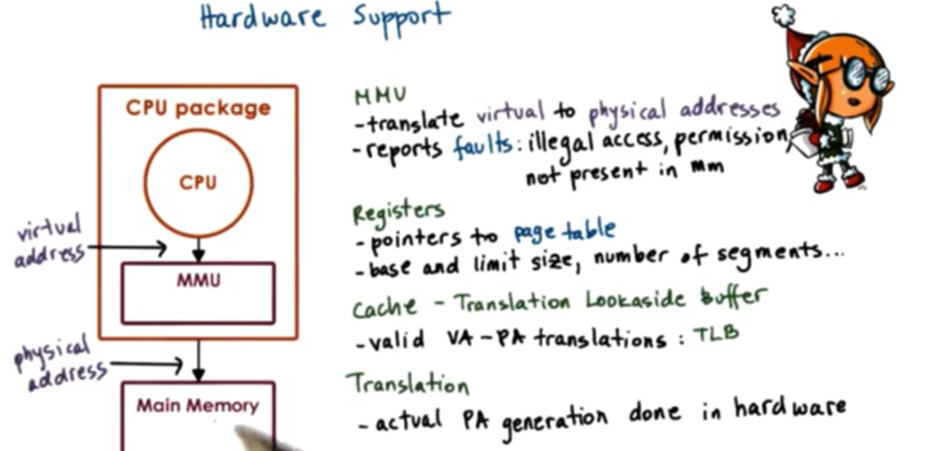

Memory management is not done by the operating system alone. Hardware mechanisms help make memory management decisions easier, faster and more reliable.

Every CPU package contains a memory management unit (MMU). The CPU issues virtual addresses to the MMU, and the MMU is responsible for converting these into physical addresses.

If there is an issue, the MMU can generate a fault. A fault can signal that the memory access is illegal; that is, there is an attempt to access memory that hasn't been allocated. A fault could also signal that there are insufficient permissions to perform a particular access. A third type of fault can indicate that the requested page is not present in memory and must be fetched from disk.

Another way that hardware supports memory management is by assigning designated registers to help with the memory translation process. For instance, registers can point to the currently active page table in a page-based memory system. In a segmentation system, the registers may point to the base address, the size of the segment and the total numbers of segments.

Since the memory address translation happens on every memory reference, most MMU incorporate a small cache of virtual/physical address translations. This is a called the translation lookaside buffer (TLB). This buffer makes the entire translation process a lot faster.

Finally, the actual translation of the physical address from the virtual address is done by the hardware. While the operating system maintains page tables which are necessary for the translation process; however, the actual hardware performs it. This implies that the hardware dictates what type of memory management modes are available, be they page-based or segment-based.

Page Tables

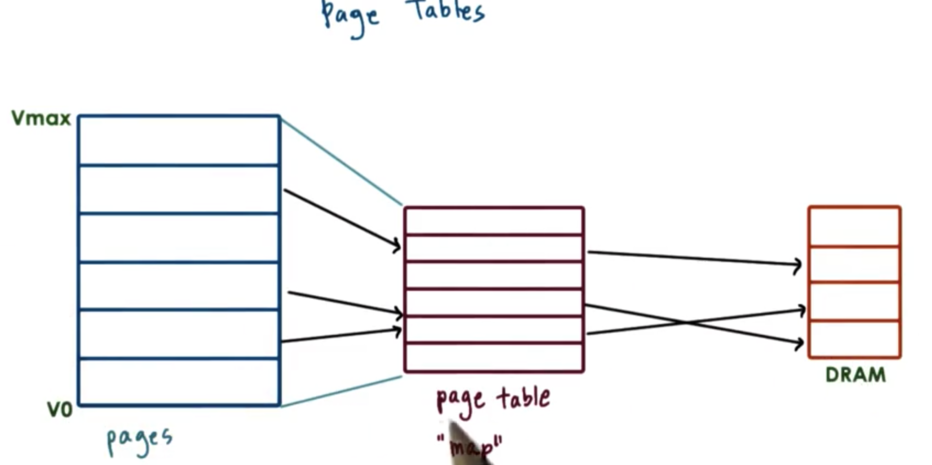

Pages are the more popular method for memory management. Page tables are used to convert the virtual memory addresses into physical memory addresses.

For each virtual address, an entry in the page table is used to determine the actual physical address associated with that virtual address. To this end, the page table serves as a map, mapping virtual addresses to physical addresses.

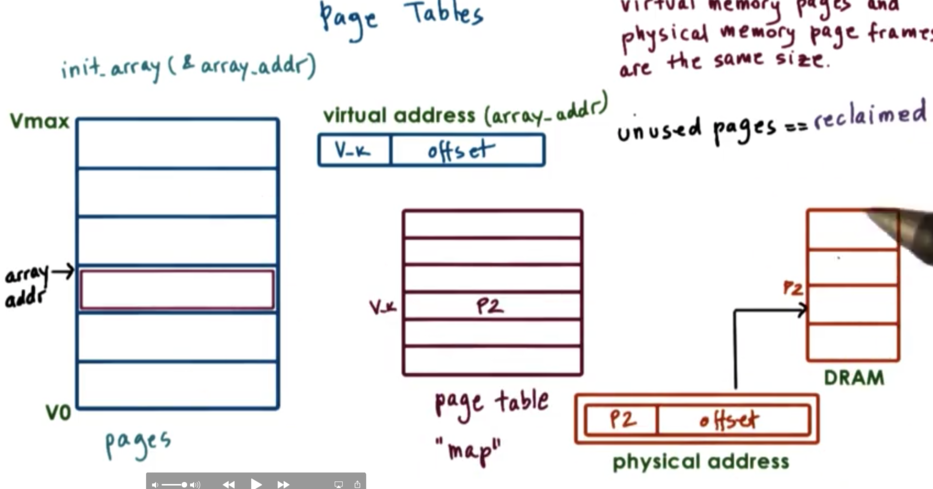

The sizes of the pages in virtual memory is identical to the sizes of the page frames in physical memory. By keeping the size of these the same, the operating system does not need to manage the translation of every single virtual address within a page. Instead, we can only translate the first virtual address in a page to the first physical address in a page frame. The rest of the memory address in the page map to the corresponding offsets in the page frame. As a result, we can reduce the number of entries we have in the page table.

What this means is that only the first portion of the virtual address is used to index into the page table. We call this part of the address the virtual page number (VPN), and the rest of the of the virtual address is the offset. The VPN is used as an index into the page table, which will produce the physical frame number (PFN), which is the first physical address of the frame in DRAM. To complete the full translation, the PFN needs to be summed with the offset specified in the latter portion of the virtual address to produce the actual physical address. The PFN with the offset can be used to reference a specific location in DRAM.

Let's say we want to initialize an array for the very first time. We have already allocated the memory for that array into the virtual address space for the process, we have just never accessed it before. Since this portion of the address space has not been accessed before, the operating system has not yet allocated memory for it.

What will happen the first time we access this memory is that the operating system will realize that there isn't physical memory that corresponds to this range of virtual memory addresses, so it will take a free page of physical memory, and create a page table entry linking the two.

The physical memory is only allocated when the process is trying to access it. This is called allocation on first touch. The reason for this is to make sure that physical memory is only allocated when it's really needed. Sometimes, programmers may create data structures that they don't really use.

If a process hasn't used some of its memory pages for a long time, it is possible that those pages will be reclaimed. The contents will no longer be present in physical memory. They will be swapped out to disk, and some other content will end up in the corresponding physical memory slot.

In order to detect this, page table entries also have a number of bits that give the memory management system some more information about the validity of the access. For instance, if the page is in memory and the mapping is valid, its valid bit will be 1. Otherwise, it will be 0.

If the MMU sees that this bit is 0 when an access is occurring, it will raise a fault and trap to the operating system. The OS has to decide if the access should permitted, and if so, where the page is located and where it should be brought into DRAM.

Ultimately, if the access is granted, there will be a new page mapping that is reestablished after access is granted. This is because it is unlikely the physical address will exist at the exact same PFN + offset as before.

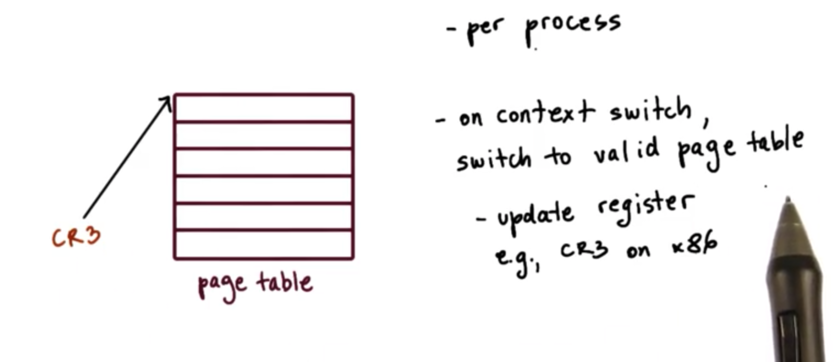

In summary, the operating system creates a page table for every single process in the system. That means that whenever a context switch is performed, the operating system must swap in the page table associated with the new process. Hardware assists with page table access by maintaining a register that points to the active page table. On x86 platforms, this register is the CR3 register.

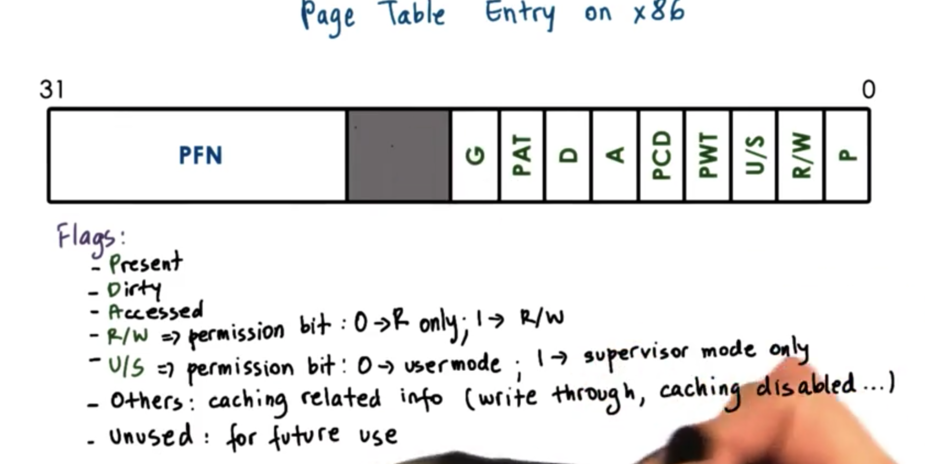

Page Table Entry

Every page table entry will have at least a PFN and a valid bit. This bit is also called a present bit, as it represents whether or not the contents of the virtual memory are present in physical memory or not.

There are number of other bits that are present in the page table entry which the operating system uses to make memory management decisions and also that the hardware understands and knows how to interpret.

For example, most hardware supports a dirty bit which gets set whenever a page is written to. This is useful in file systems, where files are cached in memory. We can use this dirty bit to see which files have been written to and thus which files need to be updated on disk.

It's also useful to keep track of an access bit, which can tell us whether the page has been accessed period, for reads or for writes.

We can also keep track of protection bits which specify whether a page is allowed to be read, written, or executed.

Pentium x86 Page Table Entry

The MMU uses the page table entry not just to perform the address translation, but also to rely on these bits to determine the validity of the access. If the hardware determines that a physical memory access cannot be performed, it causes a page fault.

If this happens, then the CPU will place an error code on the stack of the kernel, and it will generate a trap into the OS kernel, which will in turn invoke the page fault handler. This handler determines the action to take based on the error code and the faulting address.

Pieces of information in the error code will include whether or not the page was not present and needs to be brought in from disk or perhaps there is some sort of permission protection that was violated and that is why the page access if forbidden.

On x86 platforms, the error code is generated from some of the flags in the page table entry and the faulting address is stored in the CR2 register.

Page Table Size

Remember that a page table has a number of entries that is equal to the number of virtual page numbers that exist in a virtual address space. If we want to calculate the size of a page table we need to know both the size of a page table entry, and the number of entries contained in a page table.

On a 32-bit architecture, where each memory address is represented by 32 bits, each of the page table entries is 4 bytes (32 bits) in size, and this includes both the PFN and the flags. The total number of page table entries depends on the total number of VPNs.

In a 32-bit architecture we have 2^32 bytes (4GB) of addressable memory. A common page size is 4KB. In order to represent 4GB of memory in 4KB pages, we need 2^32 / 2^12 = 2^20 entries in our page table. Since each entry is 4 bytes long, we need 2^22 bytes of memory (4MB) to represent our page table.

If we had a 64-bit architecture, we would need to represent 2^64 bytes of physical memory in chunks of 2^12 bytes. Since each entry is now 8 bytes long, we need 2^3 * 2^64 / 2^12 = 32PB!

Remember that page tables are a per-process allocation.

It is important to know that a process will not use all of the theoretically available virtual memory. Even on 32-bit architectures, not all of the 4GB is used by every type of process. The problem is that the page table assumes that there is an entry for every VPN, regardless of whether the VPN is needed by the process or not. This is unnecessarily large.

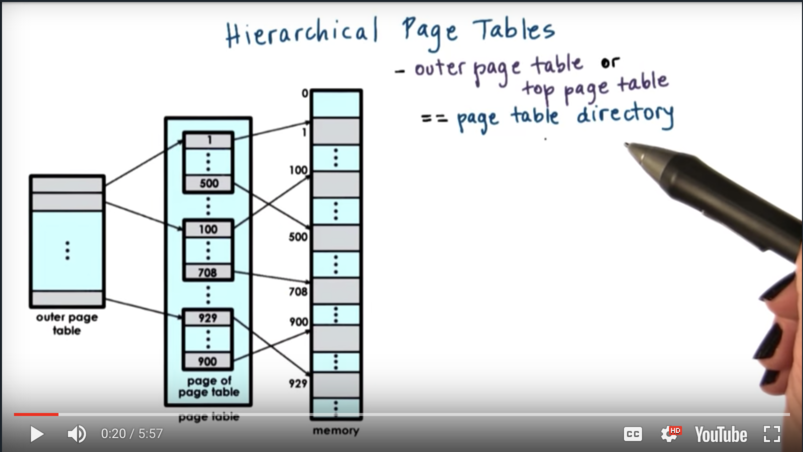

Multi Level Page Tables

We don't really design flat page tables anymore. Instead, we now use a more hierarchical page table structure.

The outer level is referred to as a page table directory. Its elements are not pointers to individual page frames, but rather pointers to page tables themselves.

The inner level has proper page tables that actually to point to page frames in physical memory. Their entries have the page frame number and all the protection bits for the physical addresses that are represented by the corresponding virtual addresses.

The internal page tables exist only for those virtual memory regions that are actually valid. Any holes in the virtual memory space will result in lack of internal page tables.

If a process requests more memory to be allocated to it via malloc the OS will check and potentially create another page table for the process the process, adding a new entry in the page table directory. The new internal page table entry will correspond to some new virtual memory region that the process has requested.

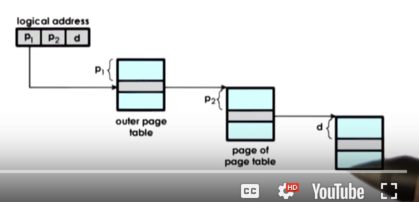

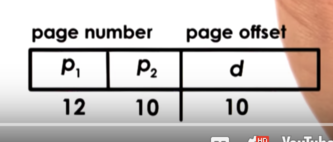

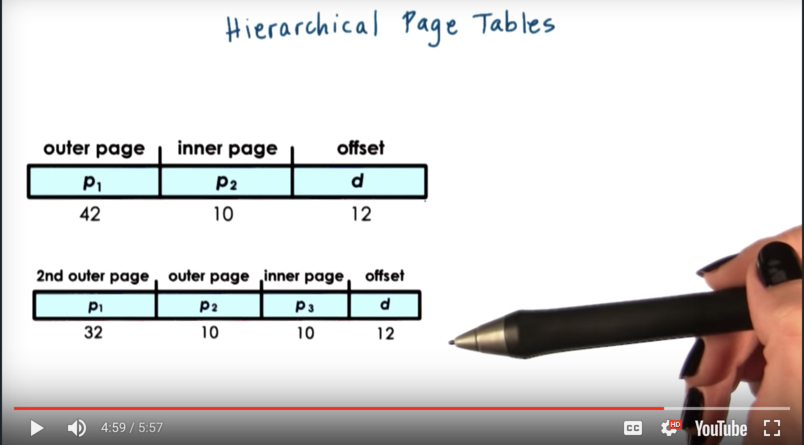

To find the right element in the page table structure, the virtual address is split into more components.

The last part of the logical address is still the offset, which is used to actually index into the physical page frame. The first two components of the address are used to index into the different levels of the page tables, and they ultimately will produce the PFN that is the starting address of the physical memory region being accessed. The first portion indexes into the page table directory to get the page table, and the second portion indexes into the page table to get the PFN.

In this particular scenario, the address format is such that the outer index occupies 12 bits, the inner index occupies 10 bits, and the offset occupies 10 bits.

This means that a given page table can contain 2^10 entries (p2), and each entry can address 2^10 bytes of physical memory (d). Loosely, we can think about the page table pointing to 2^10 "rows" of physical memory, with each row having 2^10 "cells". P2 gives us the memory "row", and d gives us the "cell" within that "row". This means that each page table can address 1MB of memory.

Whenever there is a gap in virtual memory that is 1MB (or greater), we don't need to fill in the gap with (unused) page tables. For example, if we have a page table containing pages 0-999, and we allocate another page table containing pages 30000-30999, we don't need to allocate the 29 page tables in between. This will reduce the overall size of the page table(s) that are required for a particular process. This is in contrast to the "flat" page table, in which every entry needs to be able to translate every single virtual address and it has entries for every virtual page number. There can't be any gaps in a flat page table.

The hierarchical page table can be extended to use even more layers. We can have a third level that contains pointers to page table directories. We can add a fourth level, which would be a map of page table directory pointers.

This technique is important on 64-bit architectures. The page table requirements are larger in these architectures (think about how many bits can be allocated to p2 and d), and as a result are often more sparse (processes on 64-bit platforms don't necessarily need more memory than those on 32-bit platforms).

Because of this, we have larger gaps between page tables that are actually allocated. With four level addressing structures, we may be able to save entire page table directories from being allocated as a result of these gaps.

Let's look at two different addressing schemes for 64-bit platforms.

In the top figure, we have two page table layers, while in the bottom figure, we have three page table layers. Both figures have page frames in physical memory that are 4KB (4 * 2^10).

As we add more levels, the internal page tables/directories end up covering smaller regions of the virtual address space. As a result, it is more likely that the virtual address space will have gaps that will match that granularity, and we will be able to reduce the size of the page table as a result.

The downside of adding more levels to the page table structure is that there are more memory accesses required for translation, since we will have to access more page table components before actually accessing the physical memory. Therefore, the translation latency will be increased.

Speeding Up Translation TLB

Adding levels to our page table structure adds overhead to the address translation process.

In the simple, single-level page table design, a memory reference requires two memory references: one to access the page table entry, and one to access the actual physical memory.

In the four-level page table, we will need to perform four memory accesses to navigate through the page table entries before we can actually perform our physical memory reference. Obviously, this is slow!

The standard technique to avoid these accesses to memory is to use a page table cache. On most architectures, the MMU integrates a hardware cache used for address translations. This cache is called the translation lookaside buffer (TLB). On each address translation, the TLB cache is first referenced, and if the results address can be generated from the lookup we can bypass all of the page table navigation. If we have a TLB miss, of course, we still need to perform the actual full lookup.

In addition to the proper address translation, the TLB entries will contain all of the necessary protection/validity bits to ensure that the access is correct, and the MMU will generate a fault if needed.

Even a small number of addresses cached in TLB can result in a high TLB hit rate because we usually have a high temporal and spatial locality in memory references.

On modern x86 platforms, there is a 64-entry data TLB and 128-entry instruction TLB per core, as well as a shared 512-entry shared second-level TLB.

Inverted Page Tables

Standard page tables serve to map virtual memory to physical memory on a per process basis. Each process has its own page table, so the total amount of virtual memory "available" in the system is proportional to the amount of physical memory times the number of processes currently in the system.

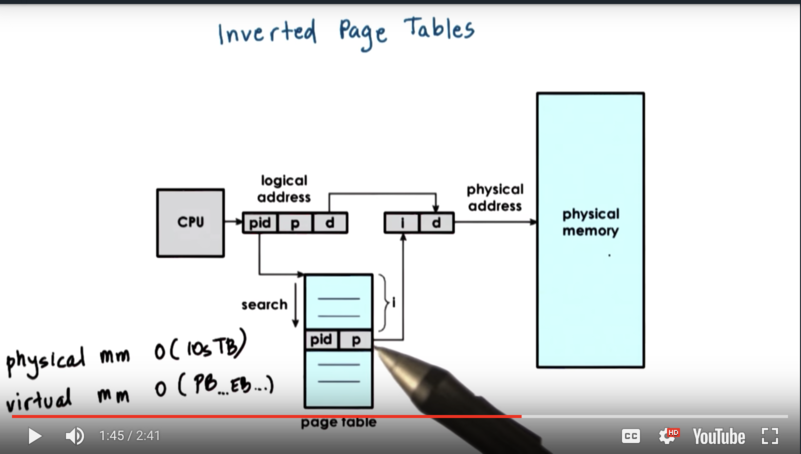

Perhaps it makes more sense to have a virtual memory representation that is closer to the physical memory layout. Here is where inverted page tables come in. Inverted page tables are managed on a system-wide basis, not on a per-process basis, and each entry in the inverted page table points to a frame in main memory.

The representation of a logical memory address when using inverted page tables is slightly different. The memory address contains the process id (PID) of the process attempting the memory address, as well as the virtual address and the offset.

A linear scan of the inverted page table is performed when a process attempts to perform a memory access. When the correct entry is found - validated by the combination of the PID and the virtual address - it is the index of that entry that is the frame number in physical memory. That index combined with the offset serves to reference the exact physical address.

Linear scans are slow, but thankfully, the TLB comes to the rescue to speed up lookups. That being said, we still have to perform these scans with some frequency, and we need a way to improve the performance.

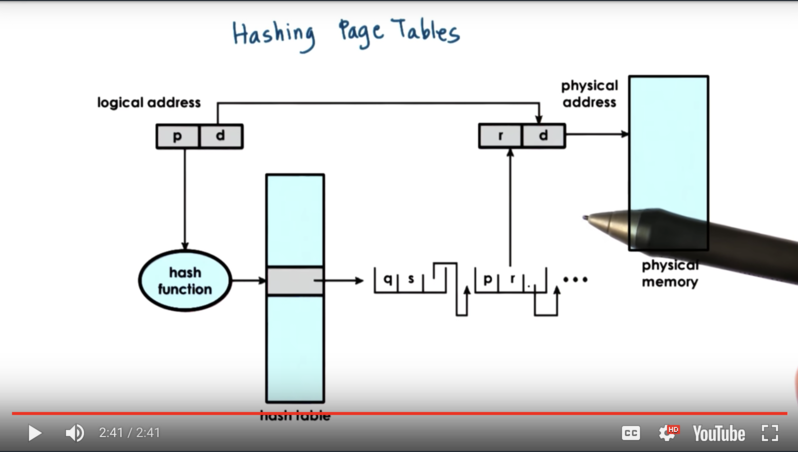

Inverted page tables are often supplemented with hashing page tables. Basically, the address is hashed and looked up in a hash table, where the hash points to a (small) linked list of possible matches. This allows us to speed up the linear search to consider just a few possibilities.

Segmentation

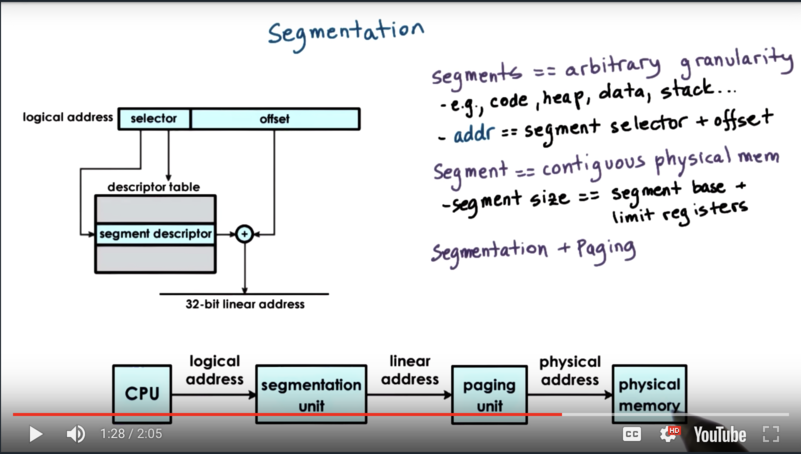

Virtual to physical memory mappings can also be maintain using segments. With segments, the address space is divided into components of arbitrary size, and the components will correspond to some logically meaningful section of the address space, like the code, heap, data or stack.

A virtual address in the segmented memory mode includes a segment selector and an offset. The selector is used in combination with a descriptor table to produce a physical address which is combined with the offset to describe a precise memory location.

In its pure form, a segment could be represented with a contiguous section of physical memory. In that case, the segment would be defined by its base address and its limit registers.

In practice, segmentation and paging are used together. The linear address that is produced from the logical address by the segmentation process is then passed to the paging unit to ultimately produce the physical address.

The type of address translation that is possible on a particular platform is determined by the hardware. Intel x86_32 platforms support segmentation and paging. Linux supports up to 8K segments per process and another 8K global segments. Intel x86_64 platforms support segmentation for backward compatibility, but the default mode is to use just paging.

Page Size

The size of the memory page, or frame, is determined by the number of bits in the offset. For example, if we have a 10-bit offset, our page size is 2^10 bytes, or 1KB. A 12-bit offset means we have a page size of 4KB.

In practice, systems support different page sizes. For Linux, on x86 platforms there are several common page sizes. 4KB pages are pretty popular, and are the default in the Linux environment. Page sizes can be much larger.

Large pages in Linux are 2MB in size, requiring an offset of 21 bits. Huge pages are 1GB in size, requiring an offset of 30 bits.

One benefit of larger pages is that more bits are used for the offset, so fewer bits are used for the virtual page number. This means that we have fewer pages, which means we have a smaller (lower memory footprint) page table. Large pages reduce the page table size by a factor of 512, and huge page tables will reduce the page table size by a factor of 1024, relative to a page size of 4KB.

Larger pages means fewer page table entries, smaller page tables, and more TLB hits.

The downside of the larger pages is the actual page size. If a large memory page is not densely populated, there will be larger unused gaps within the page itself, which will leads to wasted memory in pages, also known as internal fragmentation.

Different system/hardware combinations may support different page sizes. For example, Solaris 10 on SPARC machines supports 8KB, 4MB, and 2GB.

Memory Allocation

Memory allocation incorporates mechanisms to decide what are the physical pages that will be allocated to a particular virtual memory region. Memory allocators can exist at the kernel level as well as at the user level.

Kernel level allocators are responsible for allocating pages for the kernel and also for certain static state of processes when they are created - the code, the stack and so forth. In addition, the kernel level allocators are responsible for keeping track of the free memory that is available in the system.

User level allocators are used for dynamic process state - the heap. This is memory this is dynamically allocated during the process's execution. The basic interface for these allocators includes malloc and free. These calls request some amount of memory from kernel's free pages and then ultimately release it when they are done.

Once the kernel allocates some memory through a malloc call, the kernel is no longer involved in the management of that memory. That memory is now under the purview of the user level allocator.

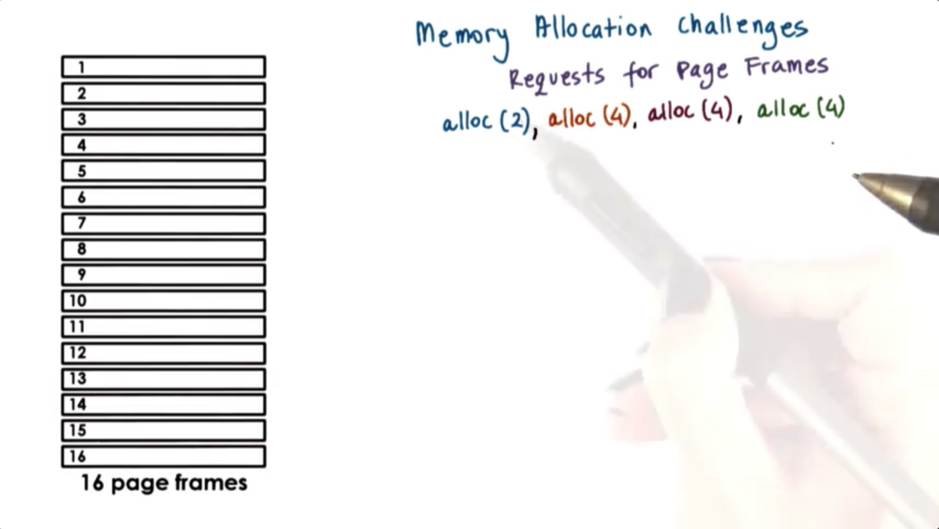

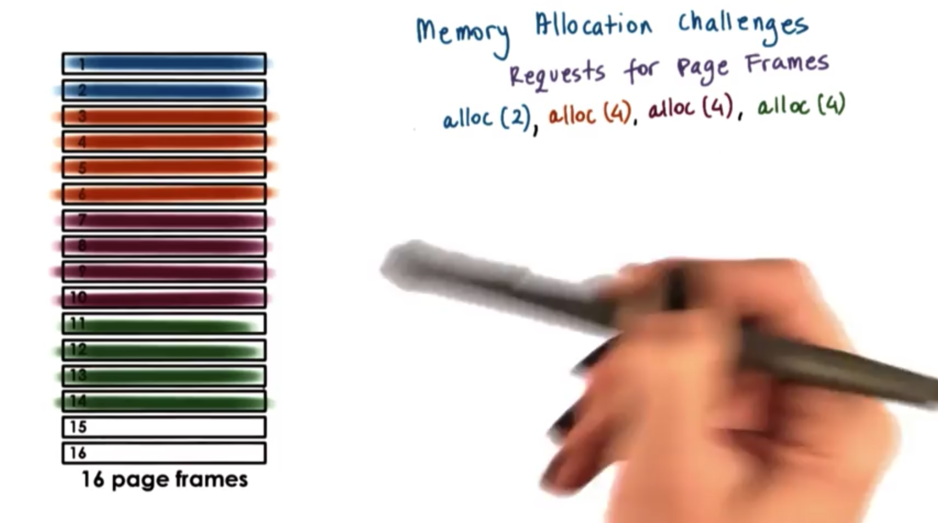

Memory Allocation Challenges

Consider a page-based memory management system that needs to manage 16 page frames. This system takes requests for 2 or 4 pages frames at a time and is currently facing one request for two page frames, and three requests for four page frames. The frames must be allocated contiguously for a given request.

The operating system may choose to allocate the pages as follows.

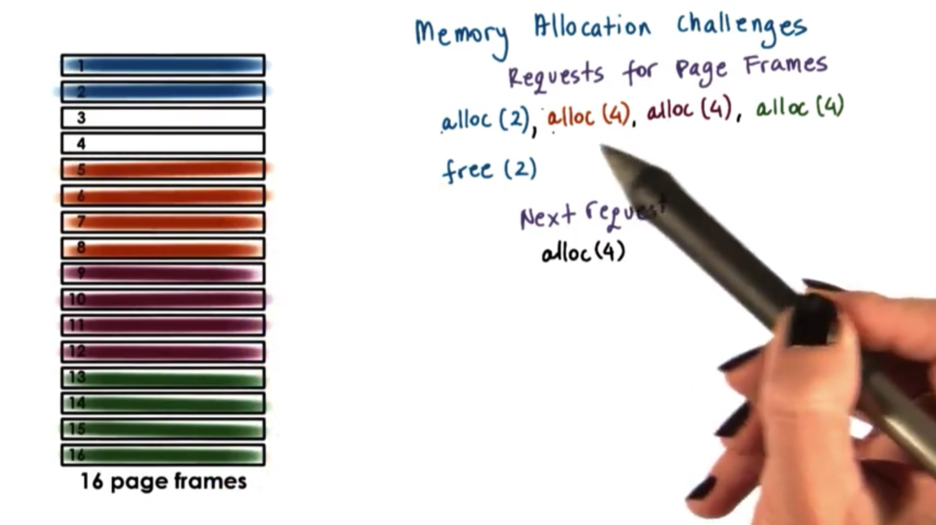

Now suppose that the initial two request frames are freed. The page table may look like this now.

What do we do when a request for four page frames comes in now? We do have four available page frames, but the allocator cannot satisfy this request because the pages are not contiguous.

This example illustrates a problem called external fragmentation. This occurs when we have noncontiguous holes of free memory, but requests for large contiguous blocks of memory cannot be satisfied.

Perhaps we can do better, using the following allocation strategy.

Now when the free request comes in, the first two frames are again freed. However, because of the way that we have laid out our memory, we now have four contiguous free frames. Now a new request for four pages can granted successfully.

In summary, an allocator must allocate memory in such a way that it can coalesce free page frames when that memory is no longer in use in order to limit external fragmentation.

Linux Kernel Allocators

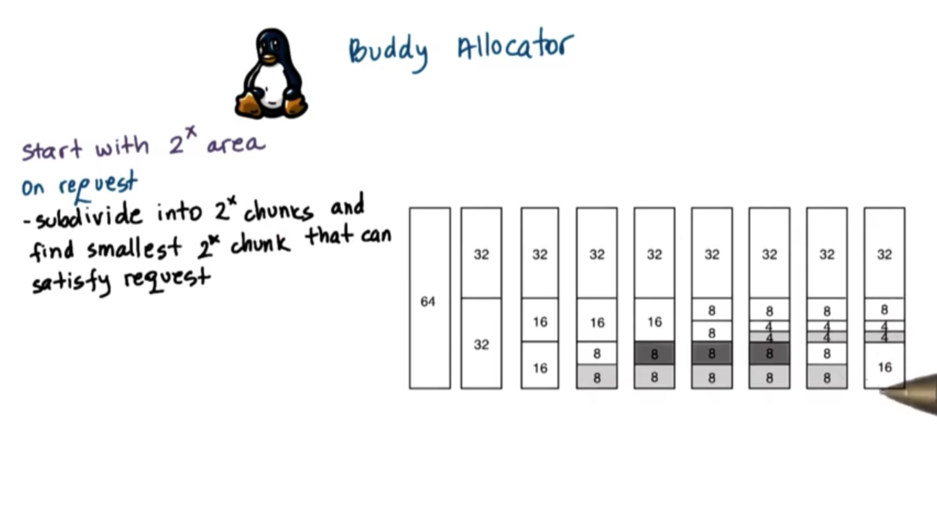

The linux kernel relies on two main allocators: the buddy allocator, and the slab allocator.

The buddy allocator starts with some consecutive memory region that is free that is a power of two. Whenever a request comes in, the allocator subdivides the area into smaller chunks such that every one of them is also a power of two. It will continue subdividing until it finds a small enough chunk that is power of two that can satisfy the request.

Let's look at the following sequence of requests and frees.

First, a request for 8 units comes in. The allocator divides the 64 unit chunk into two chunks of 32. One chunk of 32 becomes 2 chunks of 16, and one of those chunks becomes two chunks of 8. We can fill our first request. Suppose a request for 8 more units comes in. We have another free chunk of 8 units from splitting 16, so we can fill our second request. Suppose a request for 4 units comes in. We now have to subdivide our other chunk of 16 units into two chunks of 8, and we subdivide one of the chunks of 8 into two chunks of 4. At this point we can fill our third request.

When we release one chunk of 8 units, we have a little bit of fragmentation, but once we release the other chunk of 8 units, those two chunks are combined to make one free chunk of 16 units.

Fragmentation definitely still exists in the buddy allocator, but on free, one chunk can check with its "buddy" chunk (of the same size) to see if it is also free, at which point the two will aggregate into a larger chunk.

This buddy checking step can continue up the tree, aggregating as much as possible. For example, imagine requesting 1 memory unit above, and then freeing it. We would have to subdivide the chunks all the way down to 1, but then could build them all the way back up to 64 on free.

The reason that the chunks are powers of two is so that the addresses of budding only differs by one bit. For example, if my buddy and I are both 4 units long, and my starting address is 0x000, my buddy's starting address will be 0x100. This helps make computation easier.

Because the buddy allocator has granularity of powers of two, there will be some internal fragmentation using the buddy allocator. This is a problem because there are a lot of data structures in the Linux kernel that are not close to powers of 2 in size. For example, the task struct used to represent processes/threads is 1.7Kb.

Thankfully, we can leverage the slab allocator. The slab allocator builds custom object caches on top of slabs. The slabs themselves represent contiguously allocated physical memory. When the kernel starts it will pre-create caches for different objects, like the task struct. Then, when an allocation request occurs, it will go straight to the cache and it will use one of the elements in the cache. If none of the entries is available, the kernel will allocate another slab, and it will pre-allocate another portion of contiguous memory to be managed by the slab allocator.

The benefit of the slab allocator is that internal fragmentation is avoided. The entities being allocated in the slab are the exact size of the objects being stored in them. External fragmentation isn't really an issue either. Since each entry can store an object of a given size, and only objects of a given size will be stored, there will never be any un-fillable gaps in the slab.

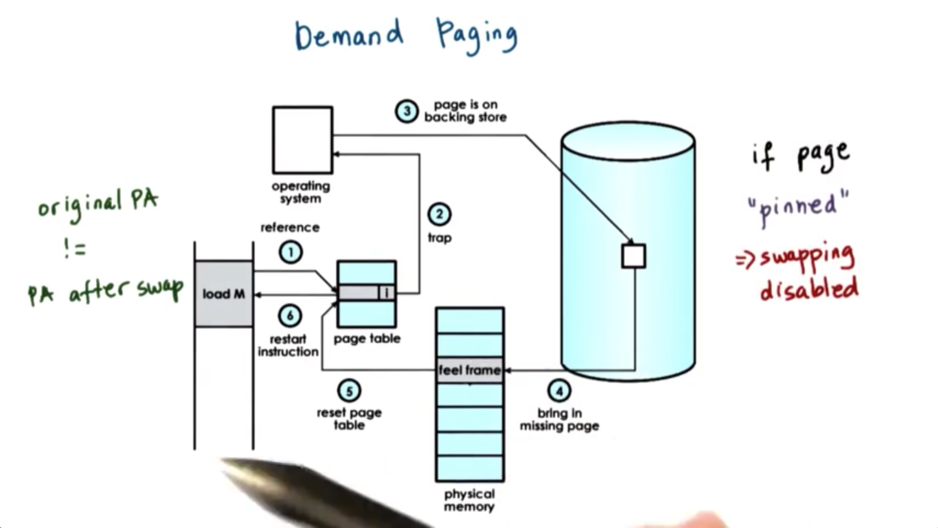

Demand Paging

Since the physical memory is much smaller than the addressable virtual memory, allocated pages don't always have to present in physical memory. Instead, the backing physical page frame can be repeatedly saved and stored to and from some secondary storage, like disk.

This process is knowing as paging or demand paging. In this process, pages are swapped from DRAM to a secondary storage device like a disk, where the reside on a special swap partition.

When a page is not present in memory, it has its present bit in the paging table entry set to 0. When there is a reference to that page, then the MMU will raise an exception - a page fault - and that will cause a trap into the kernel.

At that point, the kernel can establish that the page has been swapped out, and can determine the location of the page on the secondary device. It will issue an I/O operation to retrieve this page.

Once the page is brought into memory, the OS will determine a free frame where this page can be placed (this will not be the same frame where it resided before), and it will use the PFN to appropriately update the page table entry that corresponds to the virtual address for that page.

At that point, control is handed back to the process that issued this reference, and the program counter of the process will be restarted with the same instruction, so that this reference will now be made again. This time, the reference will succeed.

We may require a page to be constantly present in memory, or maintain its original physical address throughout its lifetime. We will have to pin the page. In order words, we disable swapping. This is useful when the CPU is interacting with devices that support direct memory access, and therefore don't pass through the MMU.

Page Replacement

When should pages be swapped out of main memory and on to disk?

Periodically, when the amount of occupied memory reaches a particular threshold, the operating system will run some page out daemon to look for pages that can be freed.

Pages should be swapped when the memory usage in the system exceeds some threshold and the CPU usage is low enough so that this daemon doesn't cause too much interruption of applications.

Which pages should be swapped out?

Obviously, the pages that won't be used in the future! Unfortunately, we don't know this directly. However, we can use historic information to help us make informed predictions.

A common algorithm to determine if a page should be swapped out is too look at how recently a page has been used, and use that to inform a prediction about the page's future use. The intuition here is that a page that has been more recently used is more likely to be needed in the immediate future whereas a page that hasn't been accessed in a long time is less likely to be needed.

This policy is known as the Least-Recently Used (LRU) policy. This policy uses the access bit that is available on modern hardware to keep track of whether or not the page has been referenced.

Other candidates for pages that can be freed from physical memory are pages that don't need to be written out to disk. Writing pages out to secondary storage takes time, and we would like to avoid this overhead. To assist in making this decision, OS can keep track of the dirty bit maintained by the MMU hardware which keeps track of whether or not a given page has been modified.

In addition, there may be certain pages that are non-swappable. Making sure that these pages are not considered by the currently executing swapping algorithm is important.

In Linux, a number of parameters are available to help configure the swapping nature of the system. This includes the threshold page count that determines when pages start getting swapped out.

In addition, we can configure how many pages should be replaced during a given period of time. Linux also categorizes the pages into different types, such as claimable and swappable, which helps inform the swapping algorithm as to which pages can be replaced.

Finally, the default replacement algorithm in Linux is a variation of the LRU policy, which gives a second chance. It performs two scans before determining which pages are the ones that should be swapped out.

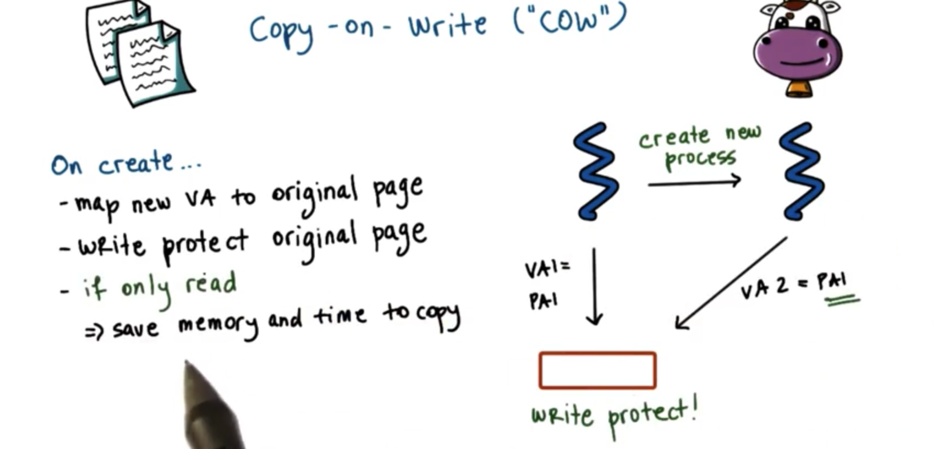

Copy On Write

Operating systems rely on the MMU to perform address translation as well as access tracking and protection enforcement. The same hardware can be used to build other useful services beyond just these.

One such mechanism is called Copy-on-Write (COW). When we need to create a new process, we need to re-create the entire parent process by copying over its entire address space. However, many of the pages in the parent address space are static - they won't change - so it's unclear why we have to incur the copying cost.

In order to avoid unnecessary copying, a new process's address space, entirely or in part, will just point to the address space of its parent. The same physical address may be referred to by two completely different virtual addresses belonging to the two processes. We have to make sure to write protect the page as a way to track accesses to it.

If the page is only going to be read, we save memory and we also save on the CPU cycles we would waste performing the unnecessary copy.

If a write request is issued for the physical address via either one of the virtual addresses, the MMU will detect that the page is write protected and will issue a page fault.

At this point, the operating system will finally create the copy of the memory page, and will update the page table of the faulting process to point to the newly allocated physical memory. Note that only the pages that need to be updated - only those pages that the process was attempting to write to - will be copied.

We call this mechanism copy-on-write because the copy cost will only be paid when a write request comes in.

Failure Management Checkpointing

Another useful operating system service that can benefit from the hardware support for memory management is checkpointing.

Checkpointing is a failure and recovery management technique. The idea behind checkpointing is to periodically save process state. A process failure may be unavoidable, but with checkpointing, we can restart the process from a known, recent state instead of having to reinitialize it.

A simple approach to checkpointing would be to pause the execution of the process and copy its entire state.

A better approach will take advantage of the hardware support for memory management and it will try to optimize the disruption that checkpointing will cause on the execution of the process. We can write-protect the process state and try to copy everything once.

However, since the process continues executing, it will continue dirtying pages. We can track the dirty pages - again using MMU support - and we will copy only the diffs on the pages that have been modified. That will allow us to provide for incremental checkpoints.

This incremental checkpointing will make the recovery of the process a little bit more challenging, as we have to rebuild the process state from multiple diffs.

The basic mechanisms used in checkpointing can also be used in other services. For instance, debugging often relies on a technique called rewind-replay. Rewind means that we will restart the execution of a process from some earlier checkpoint. We will then replay the execution from that checkpoint onwards to see if we can reproduce the error. We can gradually go back to older and older checkpoints until we find the error.

Migration is another service that can benefit from the same mechanisms behind checkpointing. With migration, we checkpoint the process to another machine, and then we restart it on that other machine. This is useful during disaster recovery, or during consolidation efforts when we try to condense computing into as few machines as possible.

One way that we can implement migration is by repeating checkpoints in a fast loop until there are so few dirtied pages that a pause-and-copy becomes acceptable - or unavoidable.

Last updated