Security Protocols

Why Security Protocols

A network protocol defines the rules and conventions for communications between two parties. A security protocol defines the rules and conventions for secure communications between two parties.

Suppose Alice and Bob want to communicate securely over the Internet. They first need to authenticate each other, so that Alice knows she is communicating with Bob and Bob knows that he is communicating with Alice.

Further, if they want to communicate securely, they likely want to encrypt their messages. Therefore, they need to establish and exchange keys and agree on what cryptographic operations and algorithms to use.

The building blocks of these security protocols are the public-key and secret-key algorithms, as well as hash functions, all of which we have previously discussed.

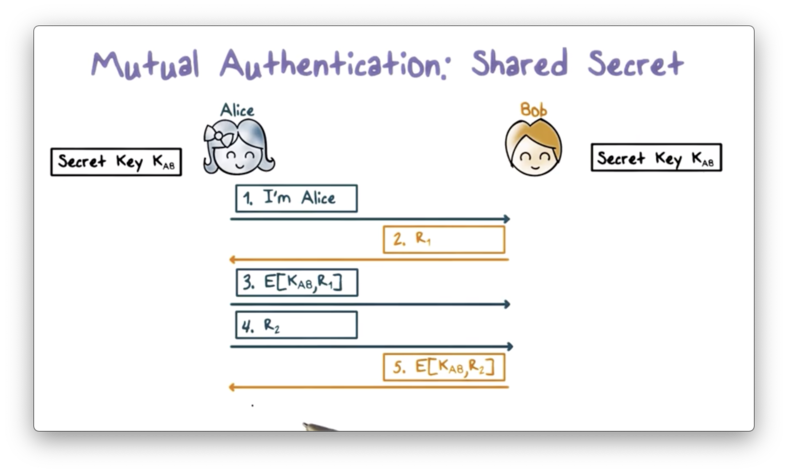

Mutual Authentication: Shared Secret

In mutual authentication, Alice needs to prove to Bob that she is Alice, and Bob needs to prove to Alice that he is Bob.

Suppose that Alice and Bob share a secret key K_AB, which only they know. Using this secret key, we can envision the following authentication protocol.

First, Alice sends a message to Bob, claiming that she is Alice. Bob response with a random value r1, referred to as a challenge. Alice encrypts r1 with K_AB and sends the ciphertext back to Bob as a response to the challenge. When Bob receives the response, he decrypts it with K_AB and sees if it matches the plaintext r1.

If there is a match, Bob knows that he must be communicating with Alice, since she is the only other person with knowledge of K_AB. Without K_AB, r1 cannot be encrypted in such a way that Bob can recover it with decryption using K_AB.

Next, Alice must authenticate Bob, and she starts by sending him a random value r2. Bob encrypts r2 with K_AB and sends the ciphertext to Alice. Upon receiving the response from Bob, Alice decrypts the ciphertext and checks if the plaintext matches r2. If so, she can be confident that she is communicating with Bob.

Note that there are cases where only one-way authentication is required. For example, if Alice is a client and Bob is a server, Alice may need to authenticate with Bob, but Bob might not authenticate with Alice. In this case, the authentication process ends after the response to r1 is received.

If Alice is a human user, then typically K_AB can be derived from a password hash that is known to Bob.

The challenge values r1 and r2 should not be easily repeatable or predictable; otherwise, an intruder Trudy can record the challenge and response between Alice and Bob and replay them to impersonate Alice or Bob.

Suppose Trudy has spent time recording the authentication messages between Alice and Bob across multiple sessions, and one of the challenge-response pairs that she recorded is {a, b}. If Bob sends a again, Trudy can impersonate Alice by responding with b.

As another example, suppose that the challenge value always increases. Trudy can first impersonate Bob and send a large challenge value, say r1 = 1000, and record the response from Alice. Meanwhile, the real Bob is using a smaller value, such as r1 = 950. When the real Bob finally sends r1 = 1000 sometime in the future, Trudy can replay the response she received earlier from Alice.

We assume that Trudy can intercept any messages delivered over the Internet, and our goal is to prevent Trudy from replaying these messages and impersonating Alice or Bob. We can achieve this goal by avoiding repeatable or predictable values for r1 and r2. Typically, we use large random values.

Additionally, we need to protect the shared secret key K_AB. If Trudy can steal a copy of K_AB from either Alice's or Bob's machine, then she can impersonate both Alice and Bob. The security of the endpoints is as important as the security of the communication between the two endpoints.

Mutual Authentication Quiz

Mutual Authentication Quiz Solution

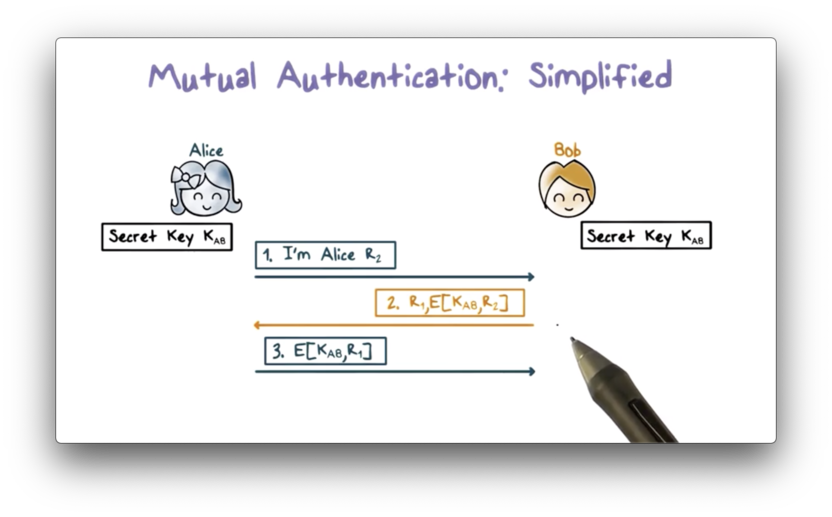

Mutual Authentication: Simplified

The mutual authentication protocol described above takes five steps. Can we shorten it to require only the following three steps?

First, Alice presents her identity to Bob and sends a challenge r2. Bob responds with both the ciphertext of r2 generated from K_AB as well as his challenge r1. Upon receiving the response, Alice decrypts the ciphertext using K_AB and validates that the plaintext matches r2 . Third, Alice sends Bob the ciphertext of r1, which Bob decrypts and compares with plaintext r1 to authenticate Alice.

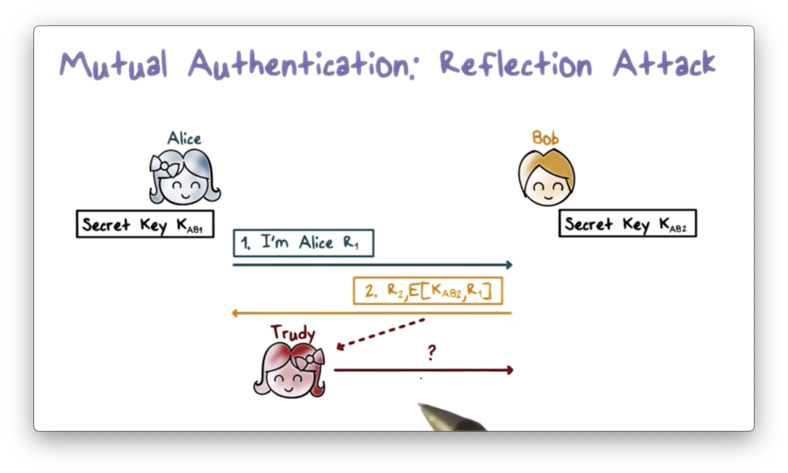

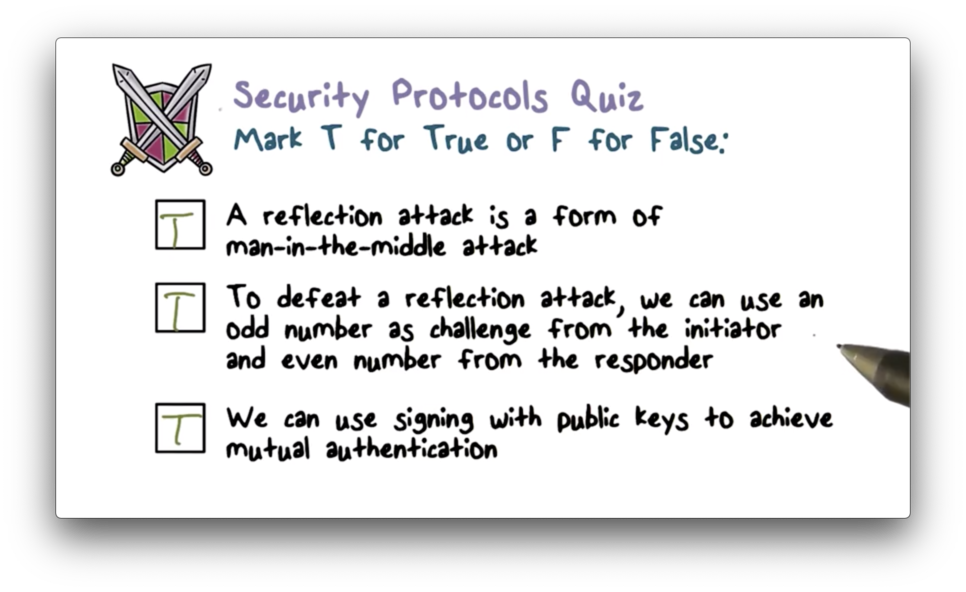

This protocol is susceptible to a reflection attack - a kind of man in the middle attack - that works as follows.

First, Trudy impersonates Alice and sends challenge r2 to Bob. According to the protocol, Trudy will be stuck at the final step of the exchange because she cannot encrypt the challenge r1 sent from Bob without K_AB.

Next, Trudy opens another connection to Bob, again impersonating Alice. Trudy sends Bob the challenge r1 that he just sent her in the first connection. Bob responds with the ciphertext for r1 and a new challenge r3.

Remember, Trudy needed the ciphertext for r1 to complete the authentication exchange in the first connection. She tricked Bob into responding to his own challenge in the second connection. Thus, Trudy can take the ciphertext from the second connection and send it back to Bob in the first connection.

This type of attack is referred to as a reflection attack because Trudy reflects Bob's challenge from the first connection back to him in the second connection.

Preventing Reflection Attacks

One strategy to defend against reflection attacks is to use two different shared keys: one for the initiator of the connection and one for the responder.

Suppose Alice uses K_AB1, and Bob uses K_AB2. In this setup, Bob sends ciphertext encrypted using K_AB2 and expects to receive ciphertext encrypted with K_AB1. Even though Trudy can intercept the challenge sent from Bob, she cannot obtain the correct ciphertext through reflection.

For example, if she sends him his own challenge, he will encrypt it with K_AB2. Unfortunately for Trudy, she needs the challenge encrypted with K_AB1, as this is the key used by Alice in responding to challenges from Bob. Since the challenge is encrypted with the wrong key, Trudy can't use it to impersonate Alice.

Another way to prevent reflection attacks is to use different challenges for the initiator and responder. For example, we can use even-numbered challenges for Alice and odd-numbered challenges from Bob.

Therefore, when Trudy receives a challenge r1 from Bob, the challenge is an odd number, and she cannot reflect this challenge back to Bob since he is expecting an even number.

Mutual Authentication Public Keys

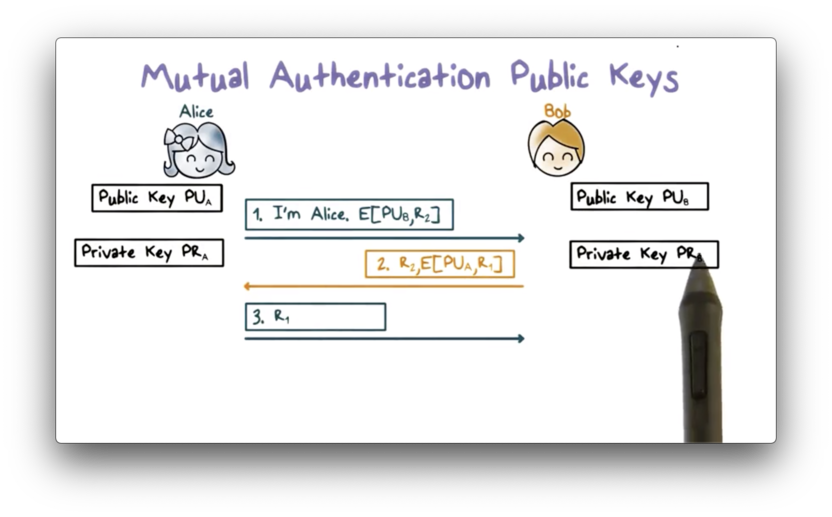

If Bob and Alice have each other's public key, they can use public-key cryptography for mutual authentication.

First, Alice sends Bob a challenge r2 encrypted with Bob's public key. Upon receiving the challenge, Bob decrypts the ciphertext using his private key, and sends back the plaintext challenge r2 along with his own challenge r1. r1 is encrypted using Alice's public key.

When Alice receives the response from Bob, the plaintext r2 lets Alice know that she is communicating with Bob because only he has the private key that pairs with the public key that encrypted r2.

Alice also decrypts the ciphertext for r1 using her private key and sends the plaintext r1 to Bob. Bob knows that he is communicating with Alice because only Alice has the private key that pairs with the public key used to encrypt r1.

This protocol can be modified to use signing with private keys instead of encrypting with public keys.

Security Protocols Quiz

Security Protocols Quiz Solution

Session Keys

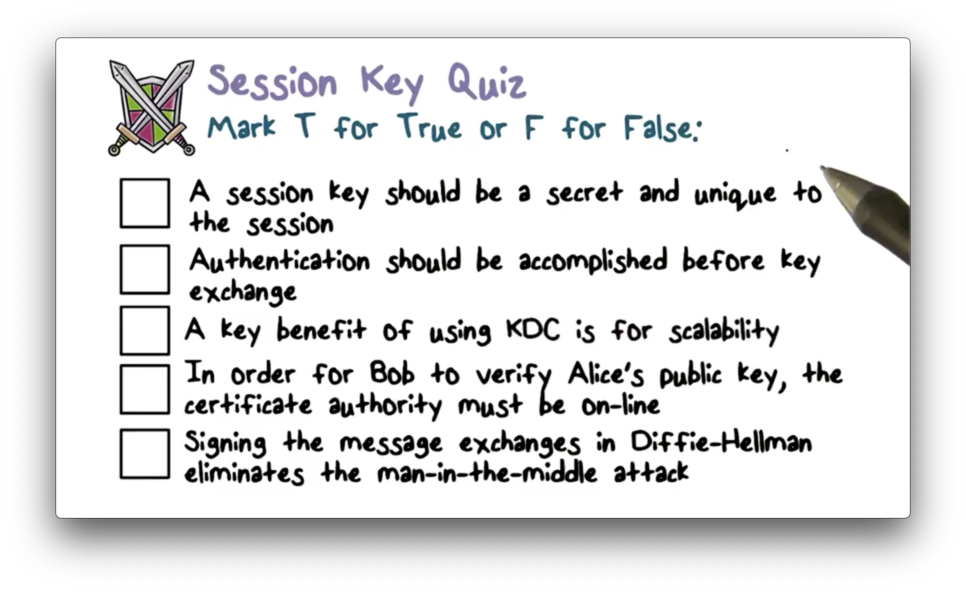

After authentication, Alice and Bob need to establish a shared secret key for their communication session so they can securely send messages to one another.

Typically, Alice and Bob share a long term secret key - called a master key - often derived from a password. Alice can use this master key K_AB to encrypt a new key K_S, which she and Bob can use for message encryption during their current communication session.

Alice and Bob should establish a new shared key for each session, even though they already share a master key. If the session key is leaked or broken, the impact is limited to the current session.

Intuitively, the more a secret is used, the higher the chance of a leak. Therefore, we should limit the use of the long-term master secret key, and only use it at the beginning of a session for authentication and establishing the session key.

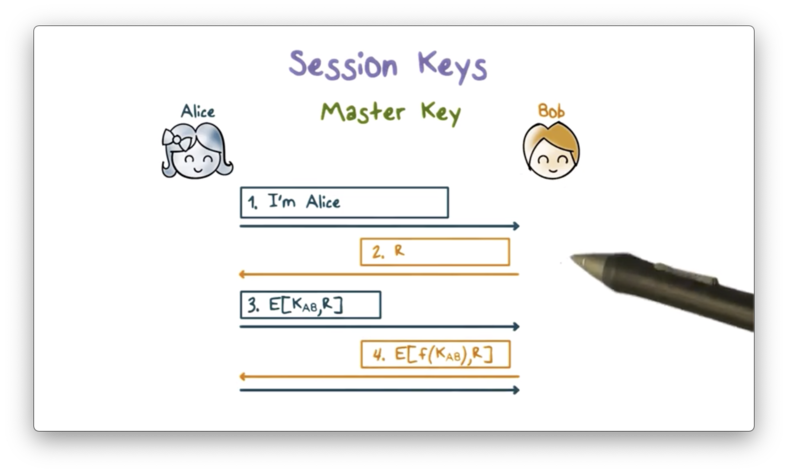

Suppose Alice and Bob share a master key, K_AB. They can establish a session key as follows. Note that the first three steps are the same as before and serve for Bob to authenticate Alice.

After authentication, Bob and Alice compute the same session key based on both K_AB and something about the current session. Incorporating information about the current session into the generation of the session key helps to ensure that the key is unique to the session.

Bob then encrypts the challenge r using this new key K_S and sends it to Alice. If Alice can decrypt r using the version of K_S that she generated, then she knows that she and Bob have generated the same session key, and communication can proceed.

Alice and Bob can also use public-key cryptography to exchange a shared session key. For example, Alice can generate a key and encrypt it with Bob's public key so that only he can decrypt it. Alice then signs the encrypted key with her private key so that Bob can verify that she genuinely sent the key.

As a third alternative, Alice and Bob can use the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol to generate and exchange their session key.

Key Distribution Center (KDC)

A major shortcoming of using pairwise key exchange based on a shared secret is that it doesn't scale well. For example, Alice needs to share a master key with Bob, Carol, and every other user with whom she wants to communicate.

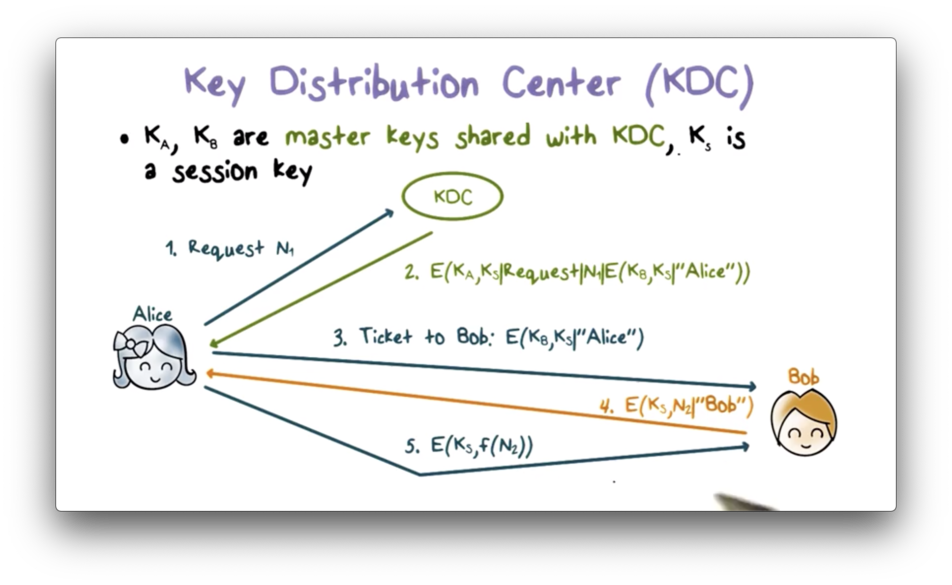

A key distribution center (KDC) solves this scalability problem. In this setup, each party holds only one master key, which they share with the KDC, and the KDC holds master keys for each enrolled party. For example, Alice may share K_A with the KDC, and Bob might share K_B with the KDC. Alice and Bob individually hold only one key, while the KDC holds both K_A and K_B.

If Alice and Bob want to have a secure session, they must first establish a session key K_S. The following diagram illustrates the steps involved in this operation.

First, Alice sends a message to the KDC containing both a request for a shared session key between her and Bob as well as a random nonce value n1. The KDC sends a response encrypted using the master key K_A that it shares with Alice.

This response contains the session key K_S that the KDC just created for Alice and Bob to share. The response also contains the original request that Alice sent to KDC along with the nonce, n1. Finally, the response contains a ticket: a message containing K_S and Alice's ID that is encrypted using the secret key K_B that Bob shares with the KDC.

When Alice receives this response, she can decrypt it because she holds K_A. She can verify that the message is not a replay by comparing the received request/nonce combination with the one she generated.

Alice then sends the ticket to Bob, which he can decrypt because he holds K_B. Bob can tell that the KDC generated the ticket because only the KDC can encrypt Alice's ID using K_B since it is the only other party in possession of that key.

Next, Bob creates a message containing a nonce n2 and his ID, encrypts it using K_S, and sends it to Alice. When Alice receives this message and decrypts it successfully, she knows that she is communicating with Bob because only he can decrypt the ticket and retrieve K_S.

Finally, Alice performs an agreed-upon transformation of n2, encrypts the result using K_S, and sends it back to Bob. This message proves to Bob that he is communicating with Alice because she is the only party that possesses K_S beside him.

Exchanging Public Key Certificates

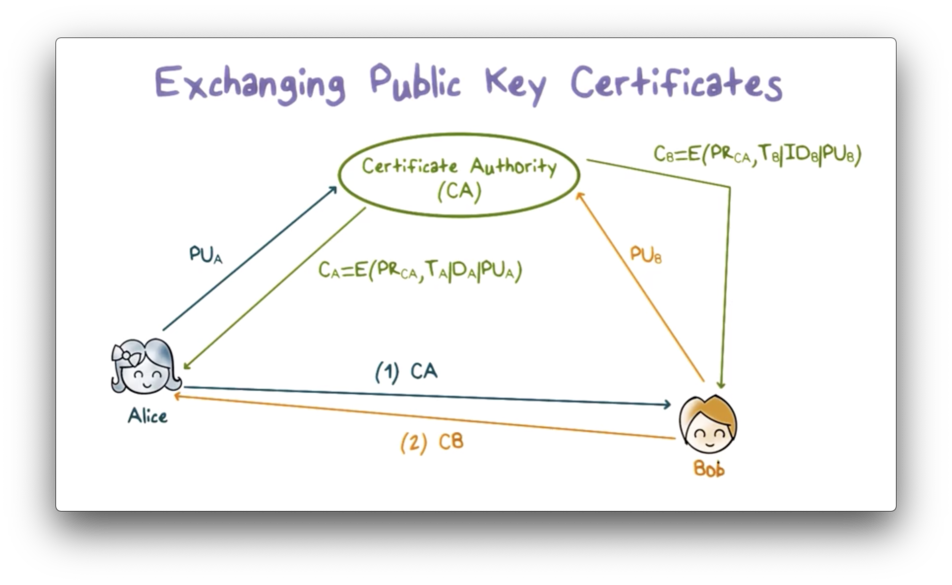

A certificate authority (CA) often manages the secure distribution of public keys.

First, Alice sends her public key to the CA, which verifies her identification and then sends her a certificate of her public key. The certificate is signed using the CA's private key and contains the certificate creation time and period of validity, as well as Alice's ID and public key.

Alice can then send this certificate to a user, such as Bob, or she can publish it so that any user can retrieve it. We assume that all users have the CA's public key, and therefore that Bob can use this public key to verify the certificate and obtain Alice's public key.

Likewise, Bob can obtain his certificate from the CA and send it to Alice so that Alice has Bob's public key as well.

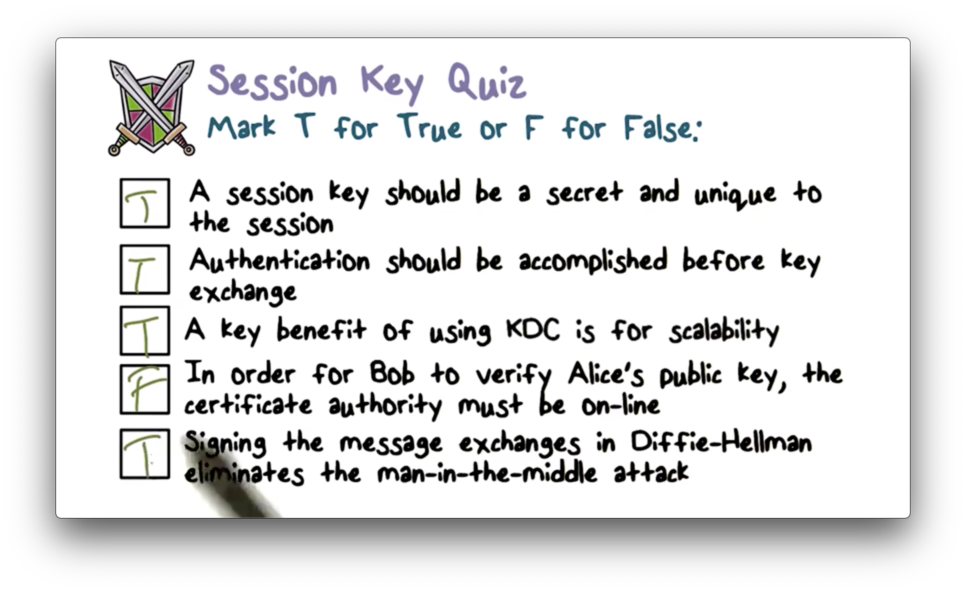

Session Key Quiz

Session Key Quiz Solution

Kerberos

Kerberos is a standard protocol used to provide authentication and access control in a networked environment, such as an enterprise network.

Every entity in the network - every user and network resource - has a master key that it shares with the Kerberos servers, which perform both authentication and key distribution. That is, a Kerberos server functions as a KDC.

For human users, the master key is derived from his or her password, while for network devices, the key must be configured in. All the keys are stored securely in the KDC.

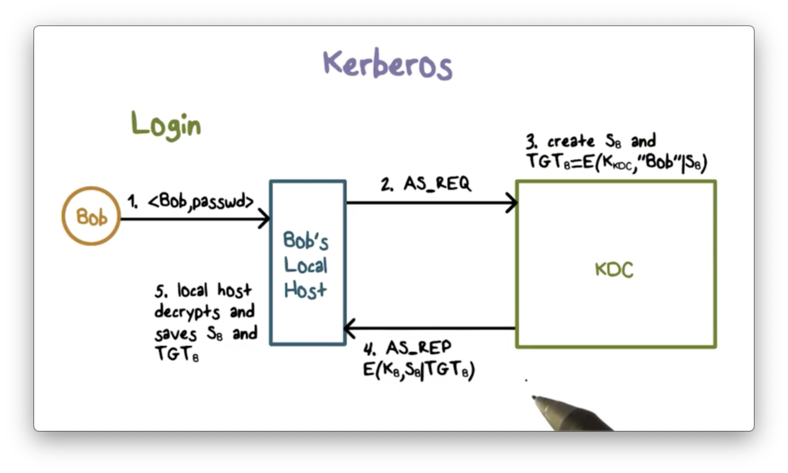

The following diagram summarizes the interactions that take place when Bob logs into a workstation backed by Kerberos.

When Bob logs in, his workstation first contacts the KDC with an authentication service request. The KDC generates a per-day session key, S_B, and a so-called ticket-granting ticket (TGT) that contains S_B and Bob's ID. This ticket is encrypted using the KDC's key.

The KDC then sends the authentication service response containing S_B and the TGT back to Bob's workstation. This message is encrypted using the master key K_B shared between Bob and the KDC.

Because K_B is shared only between Bob and the KDC, only Bob's local workstation can decrypt the authentication service response. After decryption, Bob's workstation stores S_B and the TGT.

Bob's local workstation uses S_B for subsequent messages with the KDC and includes the TGT to convince the KDC to use S_B. Any new tickets from the KDC are encrypted using S_B.

There are several benefits to this setup. First, Bob's localhost does not need to store his password or password hash once Bob has logged in and obtained S_B from the KDC.

Second, the master key K_B that Bob shares with the KDC is only used once every day when Bob initially logs in. As a result, the exposure of K_B, which is derived from Bob's password and is subject to password-guessing attacks, is very limited.

Accessing the Printer

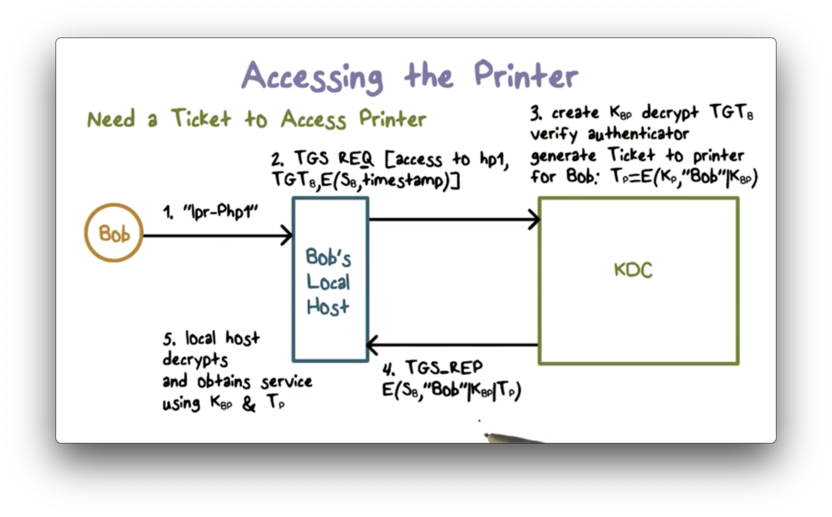

Suppose Bob wants to send a print job to a printer hp1.

His localhost sends a ticket-granting service request to the KDC. The request contains the TGT and an authenticator: the current timestamp encrypted using Bob's per-day session key S_B.

When the KDC receives the request, it decrypts the TGT using its private key K_KDC. The correct decryption of Bob's ID in the TGT verifies the validity of the TGT since only K_KDC could have encrypted it in the first place.

The KDC then uses S_B contained in the TGT to verify the authenticator by decrypting it and checking that the timestamp is current. This decryption verifies that Bob is the sender because only Bob has the key S_B that can encrypt the current timestamp properly.

The KDC then generates a ticket for Bob to communicate with the printer. This ticket contains a session key K_BP and Bob's ID, and is encrypted using the printer's master key K_P.

Note that a network device such as a printer has a long, random master key that is configured in, and is typically hard to guess or crack. Therefore, the tickets for these devices can be securely encrypted using their master keys.

The KDC sends a ticket-granting service response to Bob's localhost, which contains the session key K_BP, Bob's ID, and the ticket to the printer. The entire response is encrypted using S_B; therefore, only Bob's local workstation can decrypt it.

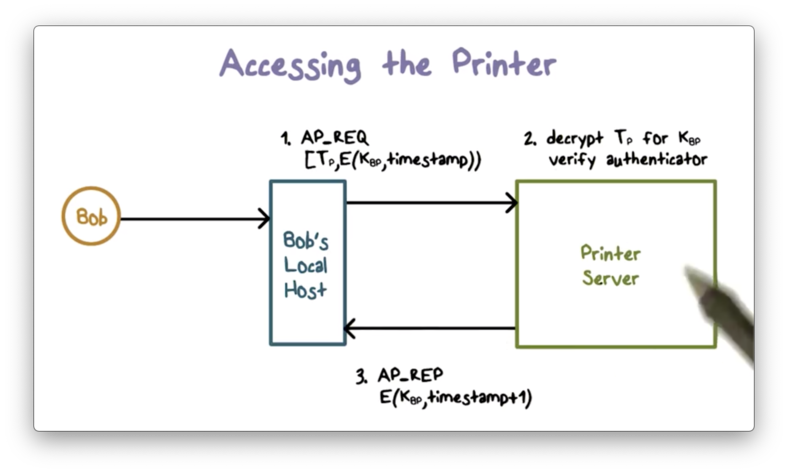

Now Bob's localhost can authenticate itself to the printer.

First, it sends an authentication request to the printer containing the ticket and a new authenticator encrypted with K_BP.

The printer decrypts the received ticket using the master key K_P it shares with the KDC because the KDC encrypted the ticket with that key.

Since the printer can verify that the KDC created the ticket - only the KDC and the printer share K_P - the printer can verify that the KDC created the shared key K_BP contained in the ticket.

The print server uses K_BP to verify the authenticator by decrypting the ciphertext and verifying that the result matches the current timestamp.

The printer then sends a response to authenticate itself to Bob by, say, adding 1 to the current timestamp, and encrypting it with the shared key K_BP.

After these authentication steps, Bob's localhost can send the print job to the printer.

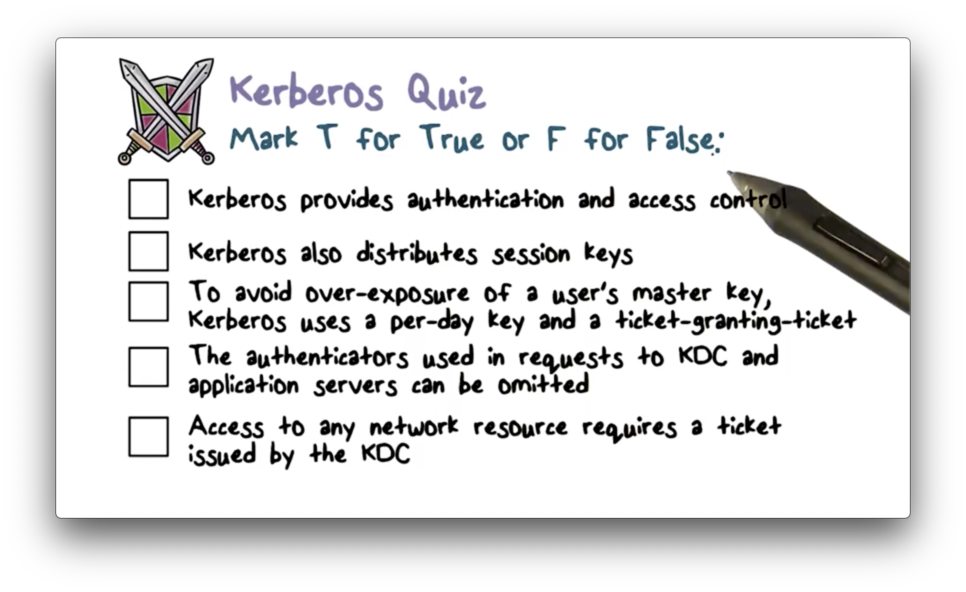

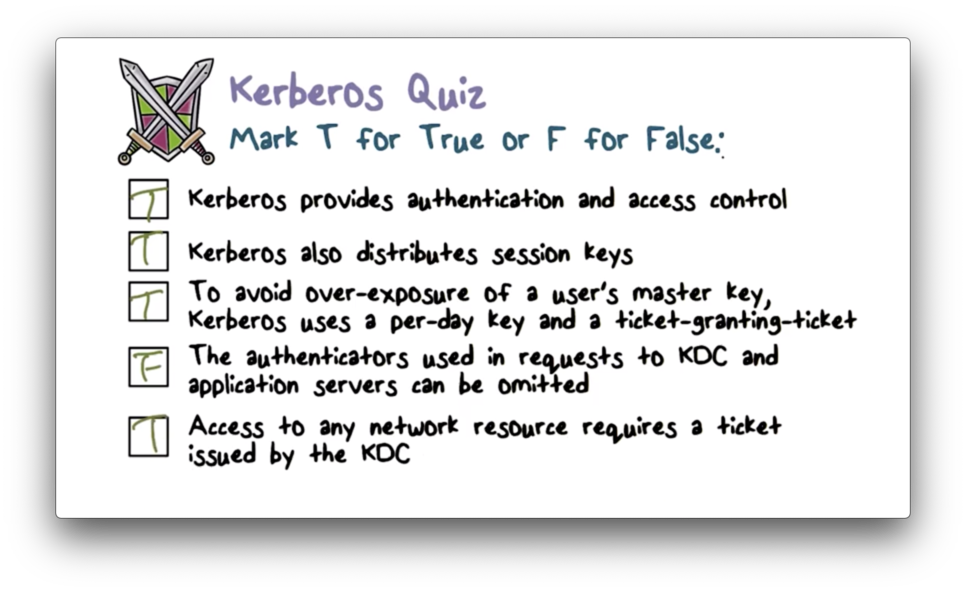

Kerberos Quiz

Kerberos Quiz Solution

Last updated