Web Security

How the Web Works

A web browser and a web server communicate using the HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP). The browser requests documents through a URL, and the server responds with documents in HyperText Markup Language (HTML).

HTML documents can include text, graphics, video, audio, PostScript, JavaScript, and other components. The browser displays text and embedded graphics and executes the JavaScript and other helper scripts.

Cookies

Each HTTP request uses its own HTTP connection; that is, HTTP is a stateless protocol. For example, when navigating through a website, each visit to a URL generates a separate HTTP (really TCP) connection.

Browsers and servers use cookies as a way of carrying information, such as user authentication/session state, across multiple HTTP requests.

Cookies are small strings of text that a web server can create as part of any HTTP response using the Set-cookie HTTP header. Cookies are essentially key/value pairs, such as userName=user123.

In addition to the key/value pair itself, a cookie also contains some metadata, including expiration information, domain information, and security requirements for transmission.

A user's browser stores cookies and includes them in subsequent requests as a way to create and preserve state over fundamentally stateless connections.

Cookie Quiz

Cookie Quiz Solution

Cookies are just strings of text. They are not compiled code, and therefore cannot infect a system the way a virus can.

The Web and Security

Can a browser trust the content it receives from the server?

Browsers rarely authenticate servers before communicating with them. Even if they do, the content that a server sends may not be trustworthy.

On the browser side, a website may have security vulnerabilities that allow it to display malicious content or execute malicious scripts. Additionally, a website might link to other websites that have security vulnerabilities themselves.

On the server side, a website runs applications that process requests from browsers and often interacts with backend servers to produce content for users.

These web applications, like any software, may have security vulnerabilities. Furthermore, many websites do not authenticate users, which means that attackers are free to send requests designed to exploit security vulnerabilities in these web applications.

Web Security Quiz

Web Security Quiz Solution

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Many websites, including social networking sites, blogs, forums, and wikis, display user-supplied data. For example, a user Joe might visit a website and fill out a form indicating that his name is Joe. The website might greet him with a page saying, "Hello Joe."

Suppose that instead of entering his name, Joe submits the following.

The website takes this string as the user's name and includes it in the HTML page sent to the browser. Therefore, when the browser displays this webpage, the script runs, and the webpage displays "Hello World."

XSS Example

In a cross-site scripting (XSS) attack, an attacker tricks the browser into executing malicious scripts without the user's knowledge.

The following diagram presents how this attack might work.

First, the user logs in to a vulnerable site, naive.com, and the browser stores a cookie to naive.com. Next, the attacker directs the user to evil.com, which returns a page containing a hidden iframe.

The iframe forces the browser to visit naive.com and invoke the hello.cgi web application, sending the malicious script as the name of the user. hello.cgi at naive.com then echos the malicious script in the HTML page sent back to the user's browser.

The browser displays the HTML page and executes the malicious script, which steals the user's cookie to naive.com and sends it to the attacker. Since the cookie can include session authentication information for naive.com, the attacker can now impersonate this user on naive.com.

XSS Quiz

XSS Quiz Solution

XSRF: Cross-Site Request Forgery

When a user logs in to a site, the server usually writes a cookie to the user's browser that contains session authentication information for that user on that site.

The cookie lives in the user's browser as long as they keep the session alive. Once they log out of the website, the server resets the cookie.

If a user browses to a malicious site in the middle of their session with a trusted site, a script on the malicious site can potentially read the user's cookie to the trusted site and use it to forge requests to that site. This type of attack is called cross-site request forgery.

The user never sees this malicious request, since the malicious site often triggers it from a hidden iframe. Additionally, the trusted server doesn't find the request suspicious since it contains the user's cookie, which the server itself granted.

XSRF Example

Here is an illustration of an XRSF example involving a trusted site, bank.com, and a malicious site, attacker.com.

The user logs in to bank.com and keeps the session alive, which means that the browser has a cookie to bank.com. Meanwhile, the attacker phishes the user and directs them to the malicious site attacker.com.

When the user visits attacker.com, their browser downloads and executes the malicious page. The scripts on this page direct the browser to make a request to bank.com on the user's behalf.

Since the user is still logged in to bank.com, their browser also sends the bank.com cookie along with the forged request. As a result, bank.com believes that the request originated from the user and therefore executes the request.

XSRF vs XSS

In cross-site scripting, an attacker injects a script into a badly-implemented website that does not validate user input. As a result, when a user visits this website, their browser downloads and executes the malicious script.

In cross-site request forgery, an attacker forges user requests to a website. As a result, the website executes the attacker's malicious actions as if they were initiated and authorized by the user.

Both XSS and XSRF are the results of security weaknesses in websites, in particular, the lack of authenticating and validating user input.

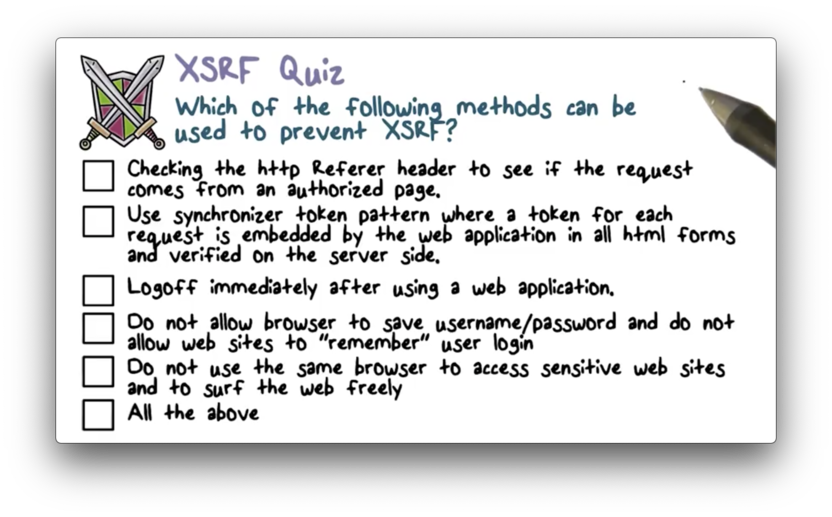

XSRF Quiz

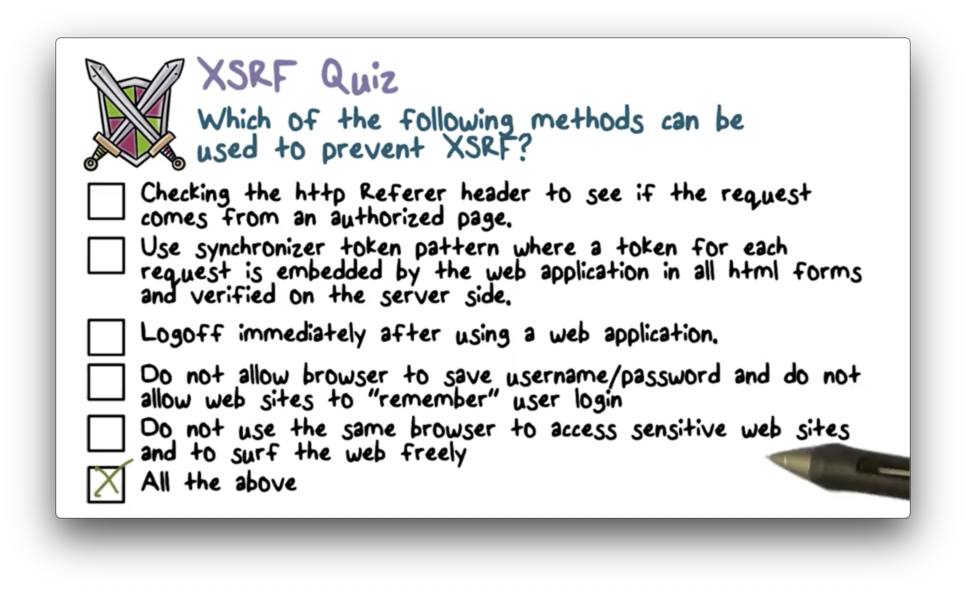

XSRF Quiz Solution

Structured Query Language (SQL)

SQL is the most widely-used database query language. We use SQL to retrieve database information, such as tables or records, and modify database information; for example, adding records to a table or modifying the specific values of a record.

Sample PHP Code

Many websites contain forms that users fill out with information that they want the database to persist. When a user submits form data, the web server typically runs a program to transform the data into an SQL query and then sends the query to the database server for execution.

For example, the following PHP snippet builds an SQL query based partially on user input.

The security threat here is that specially crafted input can generate malicious SQL queries that can lead to compromise of data confidentiality and integrity.

Example Login

Here is an example of a web form consisting of username and password fields that a user might use to log in to a web site.

To authenticate the user, the web server first needs to compare the received password hash with the stored password hash for the user. The web server issues an SQL query to the database to retrieve the stored user information.

Malicious User Input

Suppose an attacker enters this malicious string as the user name.

What is going to happen?

The SQL query sent from the web server to the backend database server triggers the deletion of all user records.

SQL Injection Quiz

SQL Injection Quiz Solution

Last updated