Content Distribution

The Web and Caching

In this lesson we'll talk about the web and how web caches can improve web performance.

We will study the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), which is an application-level protocol to transfer web content.

It's the protocol that our web browser use to request web pages. The browser, an HTTP client, sends a request to a server asking for web content, and the server responds with the content, often encoded in text.

The server usually maintains no information about past client requests: it is stateless.

HTTP is typically layered on top of a byte stream protocol, which is almost always TCP.

HTTP Requests

An HTTP request consists of multiple components, such as

request line

headers

request body (not described in this video)

Request Line

The request line contains

request method

request path

HTTP version

The request method indicates which type of request is to be performed.

Typical request methods include

GET (fetch data from server)

POST (send data to server)

HEAD (fetch headers from server)

The request path is relative to the domain of the server, and may look something like /index.html.

The HTTP version specifies the version of the HTTP protocol being used. Common values for this are 1.0 and 1.1.

Headers

The request may also contain additional headers, many of which are optional.

These include the referer, which indicates the URL from which the request originated.

Another common header is the user agent, which identifies the client software being used to request the page - such as a particular version of chrome or firefox.

Example

We can see the request line at the top, and the headers that follow.

The Accept header indicates that the client is willing to accept any content type, such as HTML, XML, or JSON.

The Accept-Language header indicates that the client would like the content to be returned in English.

The Accept-Encoding header indicates that the client is able to parse responses that are encoded in certain compression formats.

The User-Agent headers specifies that the request is coming from a Mozilla browser.

The Host specifies the domain to which the request is being made, which can be helpful when one server is hosting multiple websites at the same IP address.

HTTP Response

An HTTP response includes

status line

headers

response body (not shown in this video)

Status Line

The status line includes the HTTP version and a response code, where the response code is a number used to indicate a number of possible outcomes.

Codes in the 100s are typically informational.

Codes in the 200s are typically success, with 200 OK being common.

Codes in the 300s indicate redirection, such as 301 Moved Permanently.

Codes in the 400s indicate errors originating from the client, such as the 404 Not Found that is returned when a client requests a page that does not exist.

Codes in the 500s describe server errors, which include the dreaded 500 Internal Server Error.

Headers

The Location header may be used for redirection.

The Server header provides server information.

The Allow header indicates which HTTP methods are allowed.

The Content-Encoding header describes how the content is encoded.

The Content-Length header indicates how long the content is in terms of bytes.

The Expires header indicates how long the content can be cached.

The Last-Modified header indicates the last time the page was modified.

Example

Early HTTP

Early versions of HTTP only allowed one request/response per TCP connection.

One advantage of this approach was the simplicity of its implementation.

The main drawback of this strategy is that it requires a TCP connection for every request introduces a lot of overhead and slows transfer.

For example, the TCP 3-way handshake must occur for every request, and TCP connection must start in slow-start every time the connection opens.

This performance degradation is exacerbated by the fact that short transfers are very bad for TCP because TCP is always stuck in slow start and never gets a chance to ramp up to steady-state transfer.

Since TCP connections are terminated after every request is completed, a server will have many TCP connections that are stuck in TIME_WAIT states until the timers expire even though the response has already been delivered.

A solution to increase efficiency and account for many of these drawbacks is to use persistent connections.

Persistent Connections

Persistent connections allow multiple HTTP requests and responses to be multiplexed onto a single TCP connection.

Delimiters at the end of an HTTP request indicate the end of the request, and the Content-Length header allows the receiver to determine the length of a response.

Persistent connections can be combined with pipelining, a technique whereby a client sends the next request as soon as it encounters a referenced object.

As a result, there is as little as one RTT for all referenced objects before they begin to be fetched.

Persistent connections with pipelining is the default behavior for HTTP/1.1.

Caching

To improve performance, clients often cache parts of a webpage.

Caching can occur in multiple places.

For example, your browser can cache some objects locally on your machine.

In addition, caches can also be deployed in the network. Sometimes the local ISP may have a cache. Content distribution networks are a special type of web cache that can be used to improve performance.

Consider the case where an origin web server - that hosts the content for a given website - is particularly far away.

Since TCP throughput is inversely proportional to RTT, the further away that this web content is, the slower the web page will load. This slow down is the result of both increased latency and decreased throughput.

If instead the client could fetch content from the local cache, performance could be drastically improved as latency would be decreased and throughput increased.

Caching can also improve the performance when multiple clients are requesting the same content.

Not only do all of the clients benefit from the content being cached locally, but the ISP saves cost on transit, since it doesn't have to pay for transferring the same content over expensive backbone links.

To ensure that clients are seeing the most recent version of a page, caches periodically expire content, based the Expires header.

Caches can also check with the origin server to see if the original content has been modified. If the content has not been modified, the origin server will respond to the cache check request with a 304 Not Modified response.

Clients can be directed to a cache in multiple ways. In some cases, a user can configure their browser to point to a specific cache. In other cases the origin server might actually direct the browser to a specific cache. This can be done with a special reply to a DNS request.

We can see the effects of caching through a quick experiment with google.com.

We first use dig to retrieve the IP addresses for google.com, and when we ping one of the addresses, we see that the RTT is only 1ms.

This indicates that the content at that IP address is probably cached on the local network.

CDNs

A content distribution network (CDN) is an overlay network of web caches that is designed to deliver content to a client from the optimal location.

In many - but not all - cases the optimal location is the location that is geographically closest to the client.

CDNs are made of distinct, geographically disparate groups of servers where each group can serve all of the content on the CDN.

CDNs can be quite extensive, and larger CDNs have servers spanning the globe.

Some CDNs are owned by content providers, such as Google. Others are owned and operated by networks, such a Level 3 or AT&T. Still other CDNs are run by independent operators, such as Akamai.

Non-network CDNs, such as Google and Akamai, can typically place their servers in other autonomous systems or ISPs.

The number of cache nodes in a large CDN can vary.

In the Google network, researchers surfaced about 30,000 unique nodes. In the case of Akamai, there are about 85,000 nodes in nearly 1,000 unique networks spread out amongst 72 countries.

Challenges in Running a CDN

The underlying goal of a CDN is to replicate content on many servers so that the content is replicated close to the clients.

This goal presents a number of questions.

How should content be replicated?

Where should content be replicated?

How should clients find the replicated content?

How should the CDN choose the appropriate server replica for a particular client?

How should the CDN direct clients toward the appropriate replica once it has been selected?

Server Selection

The fundamental problem with server selection is determining which server to direct the client to.

A CDN can use many different criteria to select the server for the client, such as: the server with lowest load; the server with the lowest network latency relative to the client; or just any "alive" server.

CDNs typically aim to direct clients towards servers that provide the lowest latency since latency plays a very significant role in the web performance that clients see.

Content Routing

Content routing concerns how to direct clients to a particular server.

One strategy is to use the existing routing system.

A CDN operator could number all of the replicas with the same IP address and then rely on routing to take the client to closest replica based on the routes the internet routers choose.

Routing based redirection is simple, but it provides the service providers with very little control over which servers the clients ultimately get redirected to, since routing is dictated by the routers.

Another strategy for content routing is to use an application-based approach, such as an HTTP redirect.

This is effective but requires the client to first go to the origin server to get the redirect, which may introduce significant latency.

The most common way that server selection is performed is through the naming system, using DNS.

In this approach, the client looks up a particular domain name, such as google.com and the response contains an IP address of a nearby cache.

Naming-based redirection provides significant flexibility in directing different clients to different server replicas, without introducing any additional latency.

Naming Based Redirection

Symantec

When we look up the www.symantec.com from NYC, we don't get an A record directly. Instead, we get a CNAME record pointing to a568.d.akamai.net. When we look up the CNAME, we see 2 corresponding IP addresses.

When we perform the same lookup from Boston, we still encounter the same CNAME record. Looking up the Akamai domain name, however, returns two different IP addresses, which are presumably more local to Boston area.

Youtube

When we ping youtube.com, we can see that we get very low latency: on the order of 1ms.

A dig request for the PTR record associated with the IP address that was responding to our ping shows yh-in-f190.1e100.net which is an address from Google's CDN.

CDNs and ISPs

CDNs and ISPs have a fairly symbiotic relationship when it comes to peering with one another.

It is advantageous for CDNs to peer with ISPs.

Peering directly with the ISPs where a customer is located provides better throughput since there are no intermediate AS hops, and network latency is lower.

Having more vectors to deliver content increases reliability.

During large request events, having direct connectivity to multiple networks where the content is hosted allows the ISP to spread its traffic across multiple transit links, thereby potentially reducing the 95th percentile and lowering its transit costs.

On the other hand, it is advantageous for ISPs to peer with CDNs.

Providing content closer to the ISP's customers allows the ISP to provide its customers with good performance for a particular service.

For example, Georgia Tech has placed a Google cache node in its own network, resulting in very low latencies to Google.

Providing good service to popular services is obviously a major selling point to ISPs.

Local cache nodes also lower transit costs. Hosting a local cache prevents a lot of traffic to cached services from traversing expensive transit links, thus reducing cost.

BitTorrent

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer content distribution network which is commonly used for file sharing and distribution of large files.

Suppose we have a network with a bunch of clients, all of whom want a particular (large) file.

The clients could all fetch the same file from the origin, but this may overload the origin, and may also create congestion in the network where the file is being hosted.

Instead of having everyone retrieve the content from the origin, each client can fetch the content from other peers.

We can take the original file and chop it into many different pieces, and replicate the different pieces on many different peers in the network as soon as possible.

Each peer can share its pieces with other peers, and fetch the pieces that it doesn't have from other peers in the network who have those pieces.

By trading different pieces of the same file, everyone eventually gets the full file.

BitTorrent Publishing

BitTorrent has several steps for publishing.

First a peer creates a torrent, which contains metadata about a tracker, and all of the pieces for the file in question, as well as a checksum for each piece of the file at the time the torrent was created.

Some peers in the network need to maintain a complete initial copy of the file. Those peers are called seeders.

To download a file, the client first contacts the tracker, which contains the metadata about the file, including a list of seeders that contain an initial copy of the file.

Next, a client starts to download parts of the file from the seeder. Once a client starts to accumulate some initial chunks, it can begin to swap chunks with other clients.

Clients that contain incomplete copies of the file are called leechers.

The tracker allows peers to find each other, and also returns a random list of peers that any particular leecher can use to swap chunks of the file.

Previous peer-to-peer file sharing systems used similar swapping techniques, but many of them faced the problem of freeloading, whereby a client might leave the network as soon as it finished downloading a copy of the file, not providing any benefit to other clients who also want the file.

BitTorrent solved the problem of freeloading.

Solution to Freeriding

BitTorrent's solution to freeriding is called choking, which is type of game theoretic strategy called tit-for-tat.

In choking, if a node is unable to download from any particular peer - for example, if that peer has left the network - it simply refuses to upload to that peer.

This ensures that nodes cooperate, and eliminates the free rider problem.

Getting Chunks to Swap

One of the problems that BitTorrent needs to solve is ensuring that clients get chunks to swap with other clients.

If all the clients received the same chunks, no one would have anything to trade and everyone would have an incomplete copy of the file.

To solve this problem, BitTorrent clients use a policy called rarest piece first.

Rarest piece first allows a client to determine which pieces are the most rare among the clients and download them first.

This ensures that the most common pieces are left to the end to download, and that a large variety of pieces are downloaded from the seeder.

However, since rare pieces are typically available at fewer peers initially, downloading a rare piece may not be a good idea for new leechers. A new leecher has nothing to trade, so it is imperative to get a complete piece as soon as possible.

As a result, clients may start by selecting a random piece of the file to download from the seeder.

In the end, the client actively requests any missing pieces from all peers, and redundant requests are cancelled when the missing piece arrives.

This is ensures that a single peer with a slow transfer rate doesn't prevent the download from completing.

Distributed Hash Tables

Distributed hash tables enable a form of content overlay known as a structured overlay.

We will focus on a distributed hash table called chord, which is enabled by mechanism called consistent hashing.

Chord is a scalable, performant, distributed lookup service with provable correctness.

Chord Motivation

The main motivation of chord is scalable location of data in a large distributed system.

A publisher might want to publish the location of a particular piece of data with a particular name - for example, an mp4 with the name 'Annie Hall'.

The publisher needs to figure out where to publish this data such that a client can find it, so that when the client performs a lookup for 'Annie Hall' it's directed to the location of the mp4.

The problem that needs to be solved is the problem of lookup, which requires a simple hash function.

What makes this problem interesting, though, is that the hash table isn't located in one place, but rather it is distributed across the network.

Consistent hashing allows us to build this distributed hash table.

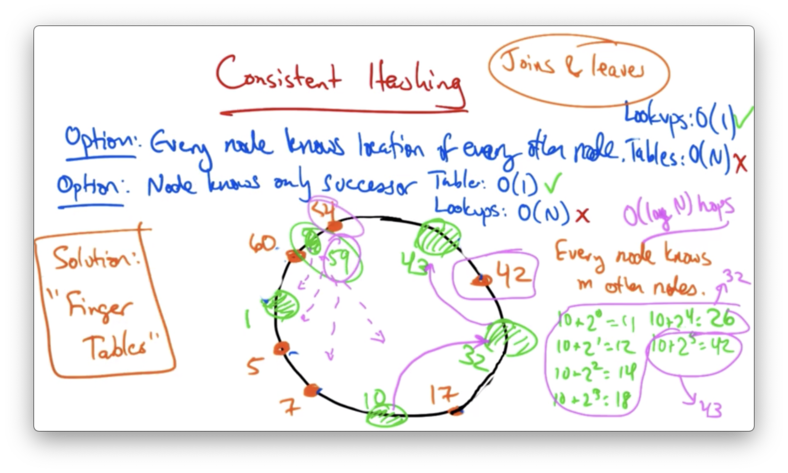

Consistent Hashing

In consistent hashing, the keys and the nodes map to the same space.

For the sake of simplicity, we can think of a space as a range of numbers. A 6-bit space is then bounded by 000000 and 111111. An element in this space can take a value from 0 to 64.

A consistent hash function, such as SHA-1 will take in a node or a key and produce an ID that is uniformly distributed in this space.

In the case of nodes, the ID might be a hash of the IP address. In the case of keys, the ID might just be the hash of the key.

The question now is how to map the key IDs to the node IDs, so we know which nodes are responsbile for resolving the lookups for a particular key.

The idea in chord is that a key is stored at its successor which is the node with the next highest ID.

Imagine the following setup, with node IDs in green and key IDs in orange.

In this case, the node with ID 32 will be responsible for the key with ID 17. The node with ID 43 will be responsible for the key with ID 42, and so on.

Consistent hashing offers the properties of load balancing because all nodes receive roughly the same number of keys, and flexibility, because when a node joins or leaves the network only a fraction of the keys need to be moved to a different node.

Implementing Consistent Hashing

To find the node responsible for a given key, there are two main strategies.

On the one hand, a node can know the location of every other node. In this case, lookups are are fast - O(1) - but the routing tables are large: O(N).

Alternatively, each node can know only its immediate successor: the node with the smallest ID larger than the current node. This makes the routing table size constant - only one entry. Unfortunately, this scheme also makes lookups grow linearly with the number of nodes.

Finger Tables

A solution that provides the best of both worlds - relatively fast lookups with relatively small routing tables - is finger tables.

With finger tables, every node knows m other nodes in the ring, and the distance to the nodes that it knows increases exponentially.

Let's construct the finger table for node 10.

The fingers of node 10 would be

10 + 2^0 = 10 + 1 = 11

10 + 2^1 = 10 + 2 = 12

10 + 2^2 = 10 + 4 = 14

10 + 2^3 = 10 + 8 = 18

10 + 2^4 = 10 + 16 = 26

10 + 2^5 = 10 + 32 = 42

The ith finger points to the successor of the node ID + 2^i. In this case, fingers 1-4 would point to node 32, and finger 5 would point to node 43.

Lookup

If node 10 wants to lookup a key corresponding to the ID 42. It can use the finger tables to find the predecessor of that node, node 32.

It then can ask node 32 for its successor. At this point, we can move forward around the ring looking for the node whose successor's ID is bigger than the ID of the data, which is node 43 in this case.

Due to the structure of the finger table, these lookups require O(log(n)) hops. The size of the finger table requires O(log(n)) state per node.

Adding Nodes

When a node joins, we must first initiate the fingers of the new node and then update the fingers of existing nodes so that they know that they can point to the node with the new ID.

In addition we must transfer the keys from the successor to the new node.

For example, when we add node with ID 59, we must transfer the ownership of key with ID 54 from node with ID 1 to the new node.

Removing Nodes

A fall back for handling leaves is to ensure that any particular node not only keeps track of its own finger table, but also of the fingers of any successor.

This way, if a node should fail at any time, then the predecessor node in the ring also knows how to reach the nodes corresponding to the entries in the failed node's finger table.

Last updated