Intrusion Detection

Defense in Depth

Recall the defense in depth principle: we need multiple layers of defense mechanisms. We typically deploy prevention systems to block attacks, but some intrusion attempts are always going to get through. If we can't stop an attack, at the very least, we need to detect it. Specifically, we need to deploy intrusion detection systems to inform us when an attack occurs.

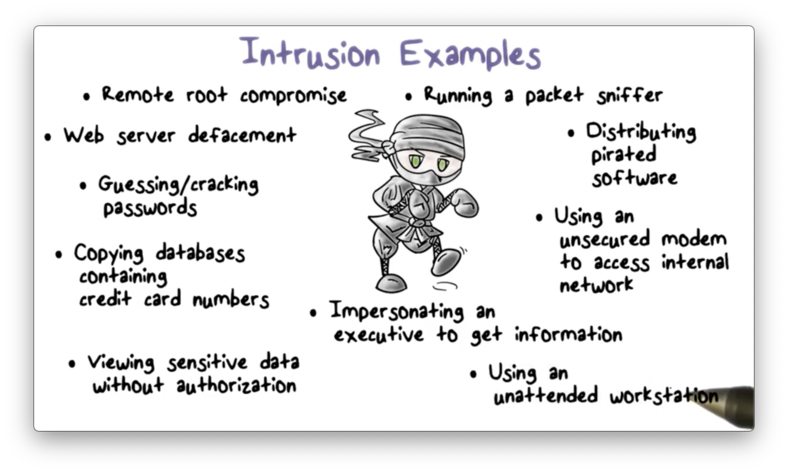

Intrusion Examples

An intrusion is any attack that aims to compromise the security goals of an organization. The following activities are all examples of intrusion.

Intrusion Detection Quiz

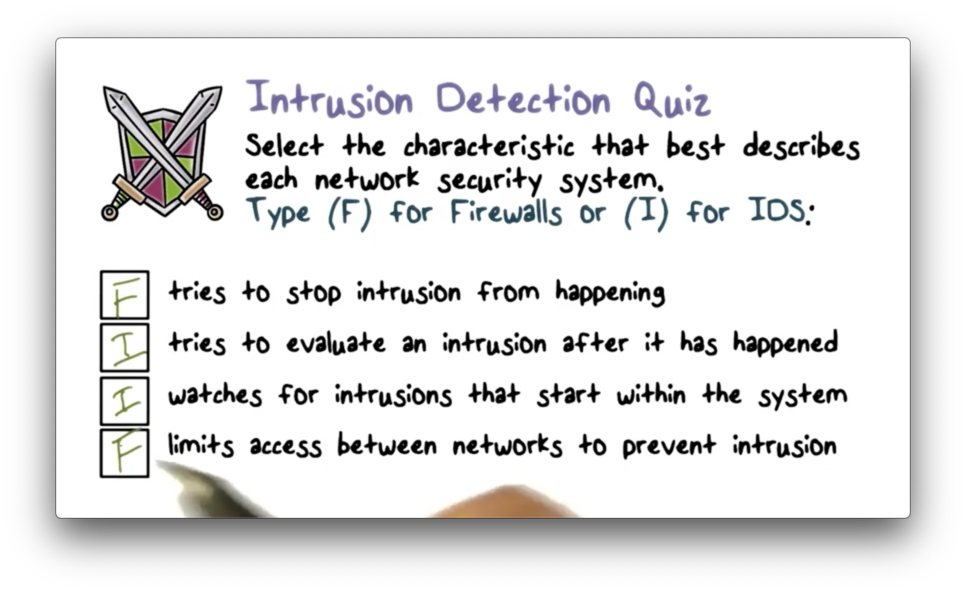

Intrusion Detection Quiz Solution

Intrusion Detection System (IDS)

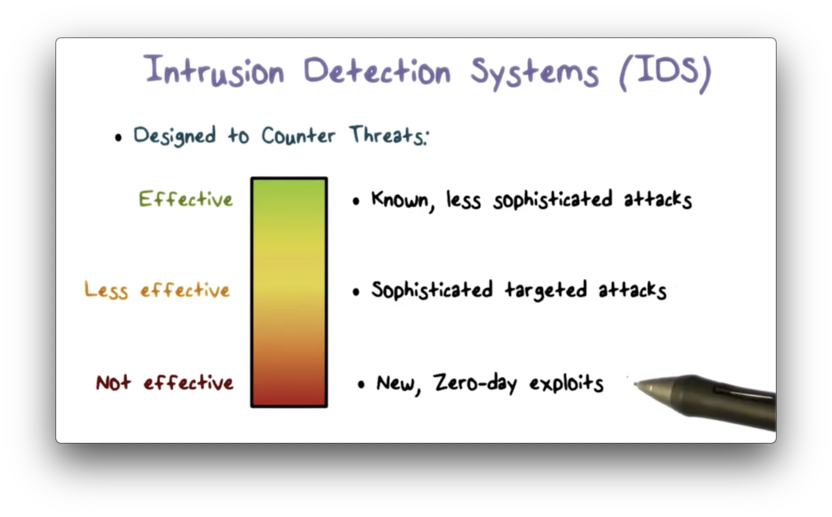

An intrusion detection system (IDS) can be quite effective against well-known or less sophisticated attacks, such as large scale email phishing attacks.

However, as attack techniques become more sophisticated, IDS's become less effective. For example, attackers can blend attack traffic with normal activities, making detection of these attacks much more difficult.

The most sophisticated attackers, such as state-sponsored individuals, may use new, zero-day exploits. IDS's are not effective against brand new types of attacks.

Since IDS's are not completely effective, they need to be part of the broader defense-in-depth strategy for an organization.

Other standard security strategies include:

encrypting sensitive information

providing detailed activity audit trails

using robust authentication and access control practices

actively managing operating system/application security

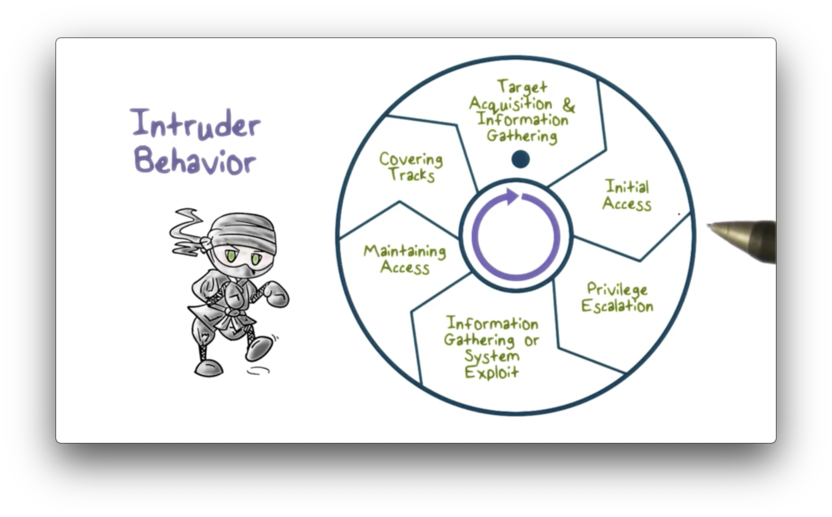

Intruder Behavior

The techniques and behavioral patterns of intruders are continually evolving to exploit newly discovered weaknesses and evade detection and countermeasures. However, attackers generally follow the same high-level steps when conducting an attack.

The following diagram illustrates these steps.

The first step is target acquisition and information gathering. An attacker identifies the target systems using publicly available technical and non-technical information.

From a technical perspective, the attacker might use network tools to analyze target resources, such as determining which network services are accessible over the Internet. A less technical step might involve looking at organizational email patterns - like lastname.firstname@company.com - to discern the addresses of some high-level executives.

The second step is the initial access. An attacker gains access by exploiting a remote network vulnerability. For example, a network service may have a buffer overflow vulnerability that an attacker can exploit remotely. Alternatively, an attacker can gain access through social engineering by, for example, sending an email with a malicious attachment to a company executive.

The third step is privilege escalation. In this step, the attacker tries to use a local exploit to escalate their privilege from an unprivileged user to a root user on the target system.

The fourth step is information gathering or system exploit. After an attacker gains sufficient privilege on a system, they can find out more about the network and the organization, and even move to another target system to advance the exploit further.

The fifth step is maintaining access. An attack might not be a one-time action; that is, an attacker may choose to come back from time to time or continue the exploit over an extended period. The attacker may install backdoors or other malicious software on the target system to maintain access.

Finally, the attacker must cover their tracks. They can edit or disable the system audit logs to remove evidence of attack activities. Alternatively, they might install rootkits to hide any installed malware.

Intruder Quiz

Intruder Quiz Solution

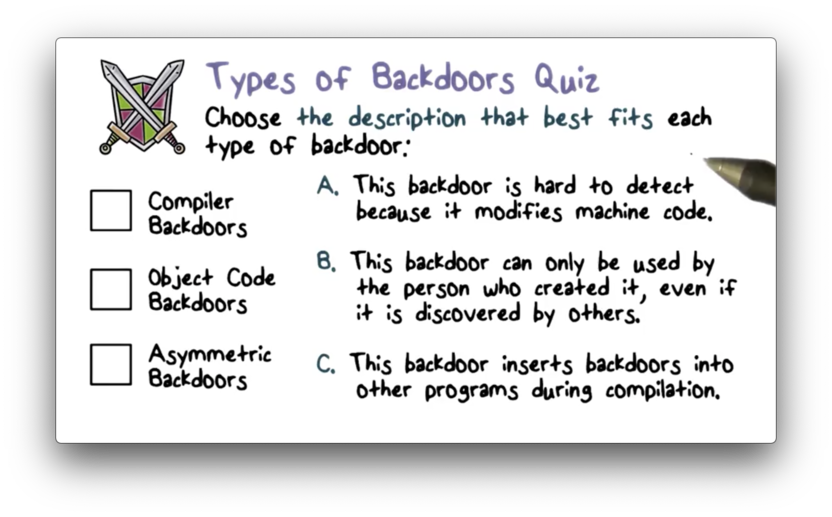

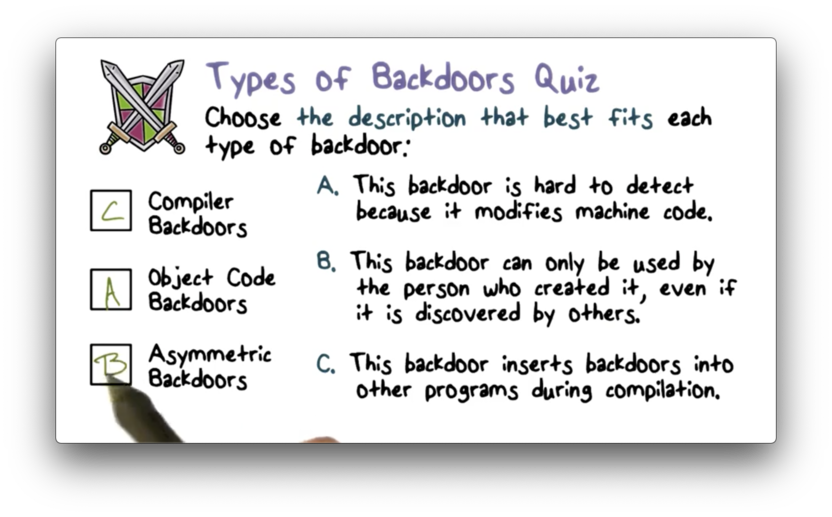

Types of Backdoors Quiz

Types of Backdoors Quiz Solution

Read more here, here, and here.

Elements of Intrusion Detection

For intrusion detection to be possible, we need to make some important assumptions. First, we have to assume that we can observe system, network, and user activities. Second, we have to assume that we can distinguish intrusive activities from ordinary activities.

When building an intrusion detection algorithm, we must consider the following. First, we need to identify the behavioral features and activities that we want to capture from the system. Second, we must synthesize our detection models; that is, we need to stitch together the evidence we collect to determine whether a pattern of activity represents an intrusion.

An IDS typically includes several modules, including:

an audit data preprocessor

a knowledge base

a decision engine

alarm generation and response mechanisms

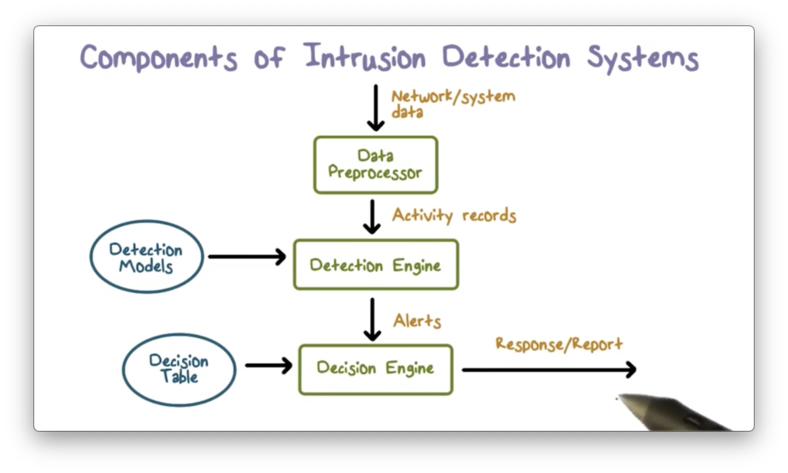

Components of Intrusion Detection Systems

The input to an IDS is network and system data that provides a snapshot of the activity currently taking place within a computer system. The data preprocessor reads this data and extracts activity records that are important for security analysis.

The detection engine analyzes the activity records using detection models packaged with the IDS. If a detection rule determines that an intrusion is happening, the IDS produces an alert.

The decision engine responds to the alert and decides the appropriate action according to a decision table. In one case, an action might be tearing down a particular network connection while, in another case, the action might be sending a report to the security admin.

Again, for the IDS to work correctly, we must be able to assume that system activities are observable and that ordinary and intrusive activities have distinguishable features.

Intrusion Detection Approaches

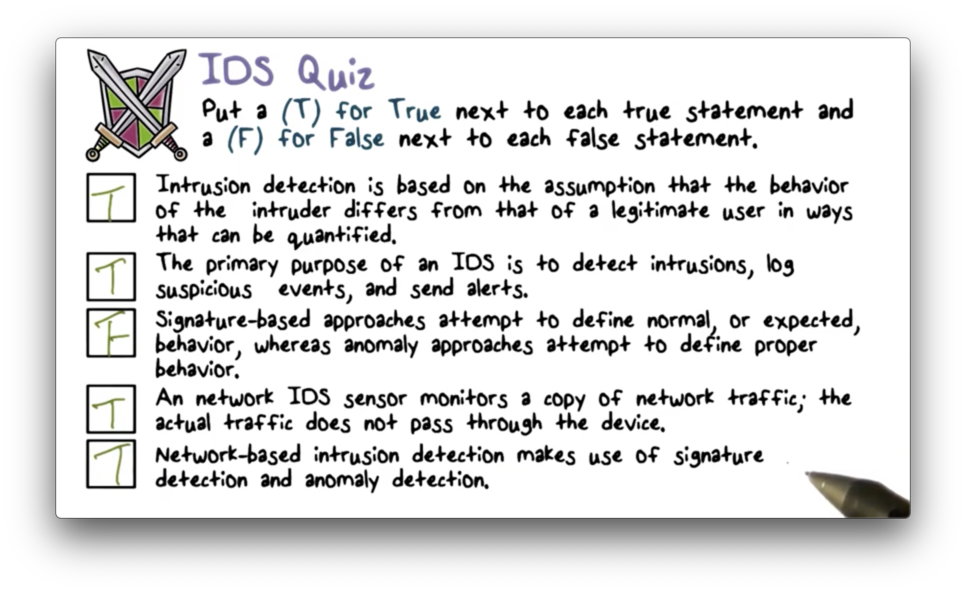

From a modeling and analysis perspective, there are two different approaches to intrusion detection. The misuse detection - signature-based - strategy models known intrusions, while anomaly detection models look for abnormal behavior, regardless of whether they have explicitly been seen previously in exploits.

From a deployment perspective, we can position an IDS on end hosts or at network perimeters.

From a development and maintenance perspective, we can create build detection models using manual encoding of expert knowledge - basically static rules translated into code - or we can apply machine learning algorithms to data to automatically learn the detection rules.

Analysis Approaches

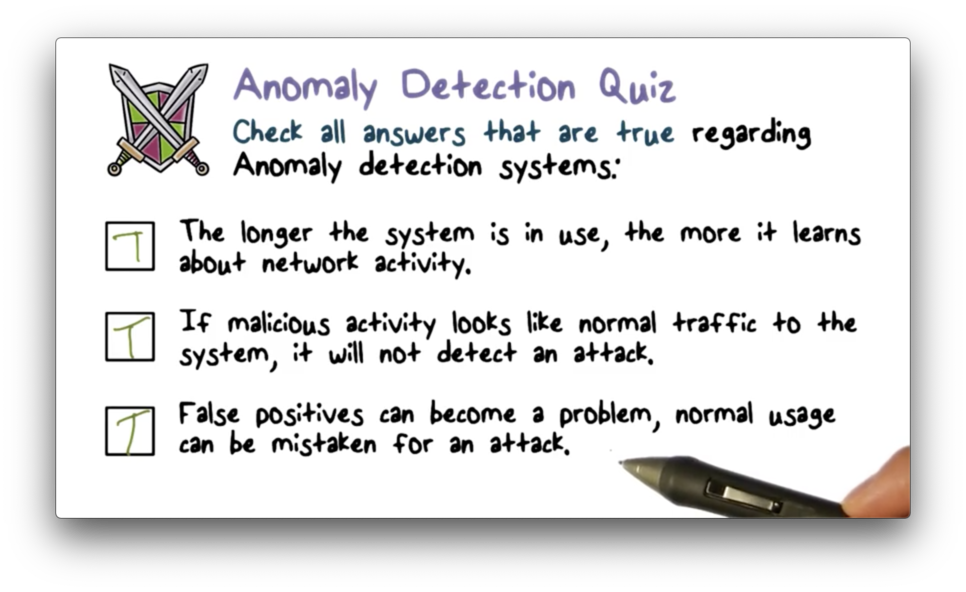

Anomaly detection consists primarily of two phases. In an initial training/profiling phase, the anomaly-based IDS collects system data corresponding to ordinary activity and uses data analysis algorithms to constructs a model representing this baseline state. After, the model continuously analyzes live system activity relative to the baseline to determine whether system activity is anomalous.

Misuse or signature-based detection involves first encoding known attacks into patterns or rules and then comparing current system activity against these patterns to determine if there is a match. Obviously, this approach can only detect known attacks.

Analysis Detection Quiz

Analysis Detection Quiz Solution

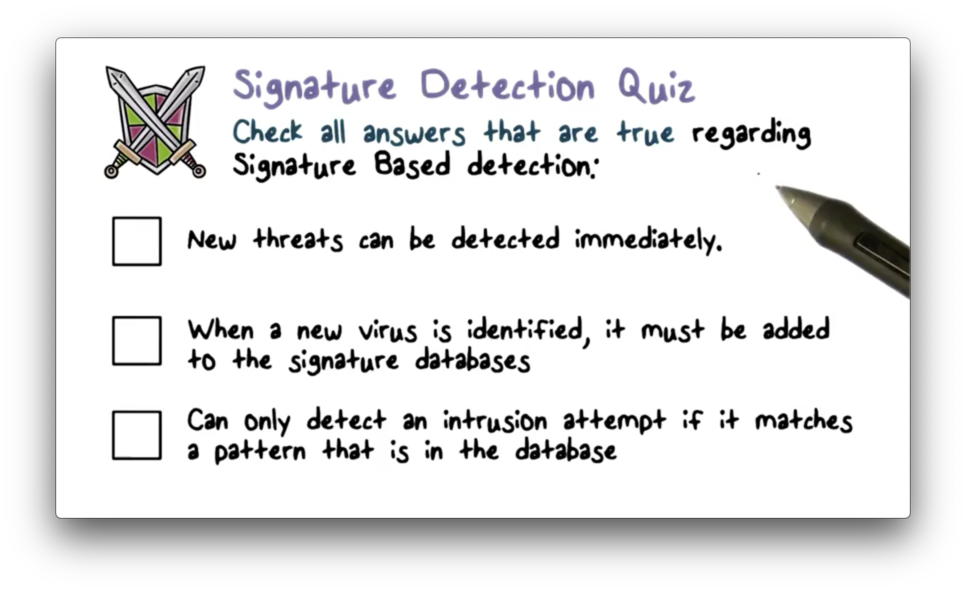

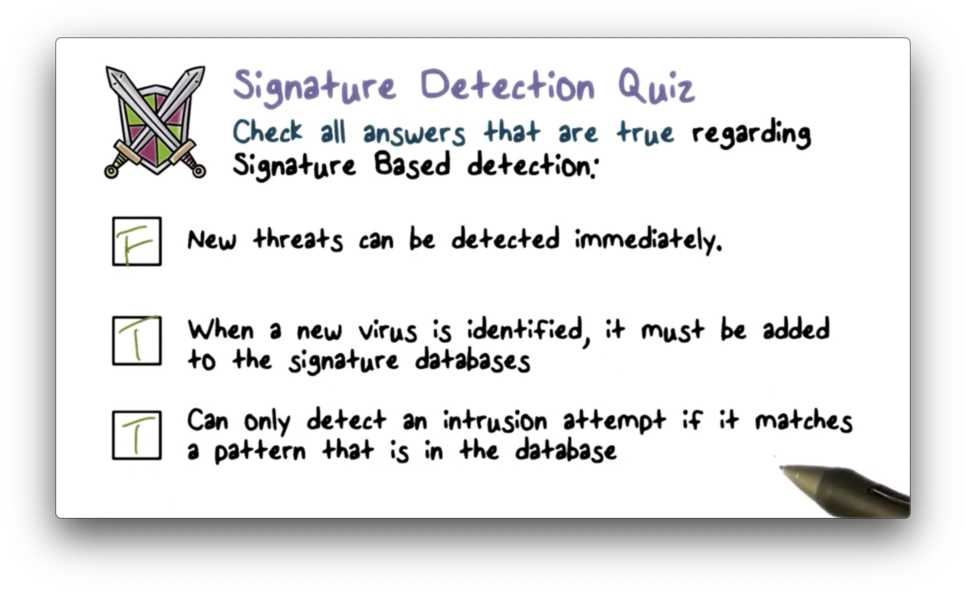

Signature Detection Quiz

Signature Detection Quiz Solution

A Variety of Classification Approaches

In the training phase, an anomaly-based IDS develops a model of normal or legitimate behaviors by collecting data from the normal operations of the monitored system or network. In the detection phase, the IDS compares observed behavior against the model and categorizes it as either legitimate or anomalous.

IDS developers can use a variety of approaches to construct these models. The statistical approach applies univariate, multivariate, or time-series models to observed metrics. The knowledge-based approach encodes legitimate behavior into a set of rules using expert knowledge. The machine learning approach uses data mining and machine learning techniques to learn a model from training data automatically.

When we compare these approaches, we need to consider both efficiency - how quickly can a system learn and apply a model - and cost - how much data and computation power we need to build that model.

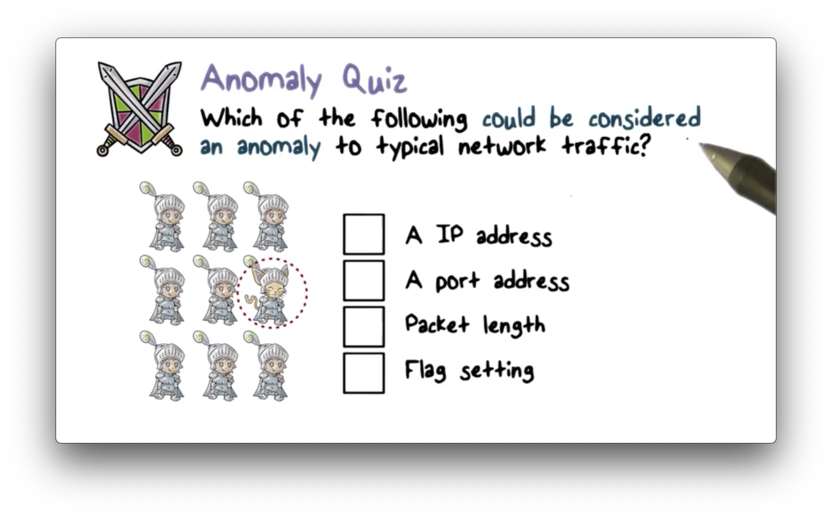

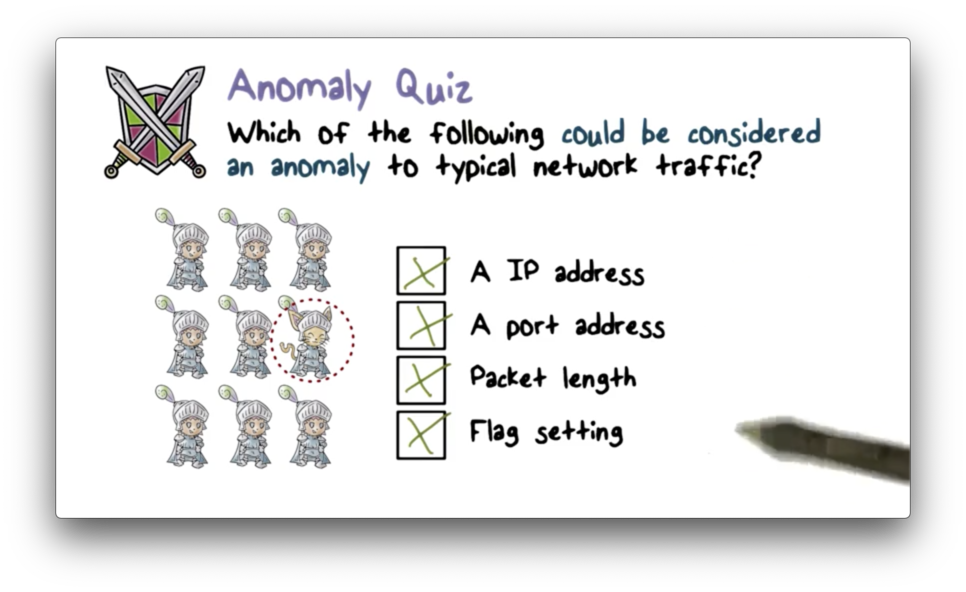

Anomaly Quiz

Anomaly Quiz Solution

Statistical Approaches

Statistical approaches use captured system data as training input to develop a model of normal behavior. The earliest approaches used univariate models, where each metric - the CPU utilization of a program, for example - was treated as an independent random variable.

However, this approach was too crude to detect intrusions effectively. Later statistical systems used multivariate models that consider the correlations between the measures. For example, these systems might examine both CPU utilization and memory size of a program together.

More recent systems incorporate time-series models that consider the order and timing between observed events. For example, these systems might examine the amount of time elapsed between when a user logs into a workstation and when that workstation sends an email.

The main advantage of statistical approaches is that they are relatively simple, easy to compute, and they don't have to make many assumptions about behavior. On the other hand, the effectiveness of these approaches relies on selecting the right set of metrics to examine and correlate, which is a difficult task. Additionally, there are complex behaviors that are beyond the capability of these models.

Knowledge Based Approach

Knowledge-based approaches require experts to develop a set of rules that describe the normal, legitimate behaviors observed during training. These rules can separate activities into different classes; for example, a rule might state that a secretary normally only uses office productivity programs, like web browsers, email, calendar, and Microsoft office.

These rules can be quite robust, and systems built with this approach are relatively easy to update and improve. On the other hand, these approaches rely on manual efforts of experts, and these experts must have strong knowledge of the data and the domain.

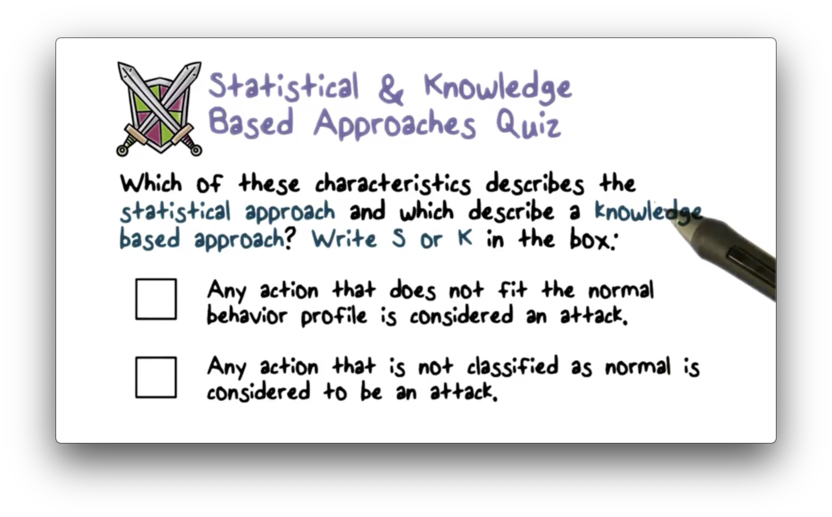

Statistical & Knowledge Based Approaches Quiz

Statistical & Knowledge Based Approaches Quiz Solution

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning approaches can build a model automatically using the labeled, normal training data. A machine learning algorithm takes as input examples of normal data and outputs a model that is then able to classify subsequently observed data as either normal or anomalous.

Machine learning models are powerful in that they can handle small changes or variations in the observed data and can also capture complex interdependencies between different observed features.

For these approaches to be effective, the normal training data must be representative of normal behaviors; otherwise, the learned model can produce many false positives. Additionally, the training phase of machine learning requires a lot of data, and significant time and computational resources. However, once the model is produced, subsequent analysis is typically reasonably efficient.

Machine Learning Intruder Detection Approaches

IDS can use a variety of machine learning algorithms.

Bayesian networks encode the conditional probabilities between observed events - the probability that a user is sending an email if the current time is 2 AM, for example. A system might raise an alert if it observes an event that has a significantly low probability of occurring.

Markov models are sets of states connected by transitional probabilities. For example, a system can use Markov models to model legitimate website names. The transitional probabilities from one letter to the next in a URL should be similar to that of real dictionary words.

On the other hand, a randomly-spelled website name is anomalous and might indicate a botnet C&C server, since bots don't have to type out URLs.

Neural networks simulate how human brains perform reasoning and learning and are one of the most powerful machine learning approaches.

Clustering groups training data into clusters based on some similarity or distance measure and then identifies subsequently observed data as either a member of a cluster or an outlier.

For example, legitimate traffic from an internal network to an internal web server shares common characteristics that can be grouped into clusters based on the web pages visited. On the other hand, an attack may access data on the web server that is rarely visited, making it an outlier.

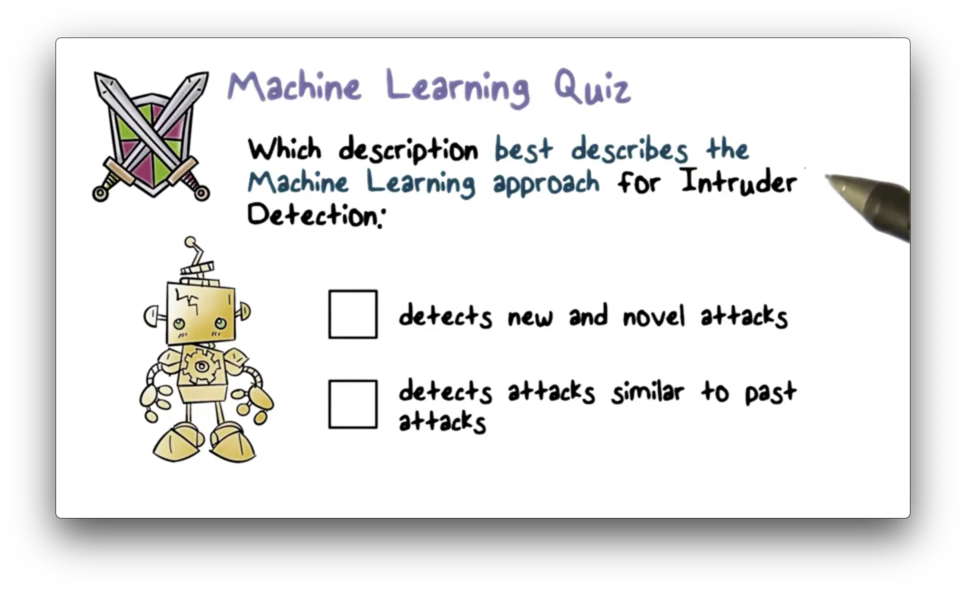

Machine Learning Quiz

Machine Learning Quiz Solution

Limitations of Anomaly Detection

A fundamental limitation of anomaly detection models is that they train using only normal or legitimate data. Since these models do not see any intrusion data during training, they cannot be sure that a general anomaly is evidence specifically of an intrusion.

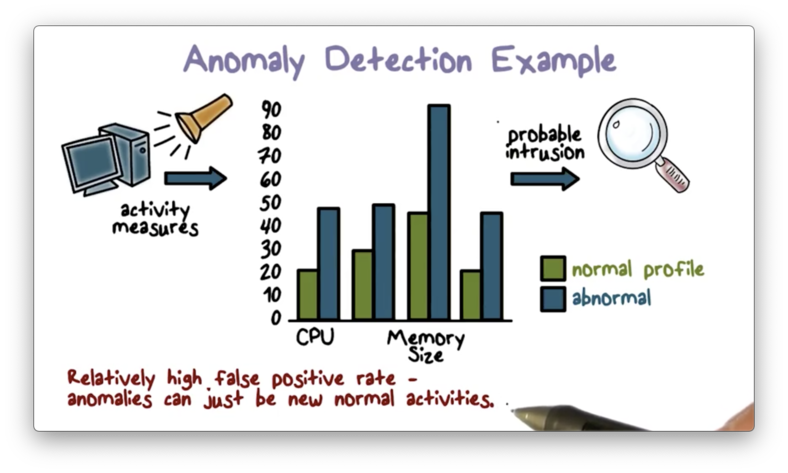

Anomaly Detection Example

Here is an example of a straightforward anomaly detection approach.

First, the system establishes a normal, statistical runtime profile of a program. The system generates this profile by running the program many times, recording important metrics - CPU utilization and memory size, for example - each time, and then computing the mean and variance for each captured metric.

Once the IDS builds the profile, it can then compare subsequent system activity against this profile. If it observes that activity deviates from the means beyond the allowed variances, the IDS outputs an alert.

Again, the main drawback of the anomaly detection approach is that it can produce relatively high false-positive rates because an anomaly can be a new, unobserved, yet normal activity.

Misuse or Signature Detection

Misuse or signature-detection systems surface intrusions by comparing activity data against a local database of known intrusion patterns. If they detect a match in activity patterns, they can conclude that an intrusion has occurred; otherwise, the system is likely functioning normally.

Anomalous Behavior Quiz

Anomalous Behavior Quiz Solution

Signature Approaches

Many misuse detection approaches use signatures, known patterns of malicious activity data, to categorize current system activity as malicious or benign. To maximize the detection rate and minimize the false-positive rate, the set of signatures against which these systems compare activity needs to be as large as possible. Signature-based approaches are most commonly found in anti-virus software and network intrusion detection systems.

Signature Approach Advantages & Disadvantages

Signatures are typically straightforward to understand, and signature matching is very efficient; therefore, signature-based approaches are widely used. On the other hand, significant manual effort must be spent to create new signatures every time a new malware or attack method appears. Additionally, these approaches cannot detect zero-day attacks because those attacks are new and do not yet have known signatures.

Zero Day Market Place Quiz

Zero Day Market Place Quiz Solution

Rule Based Detection

In addition to signature-based strategies, a misuse detection system can also use a more sophisticated, rule-based approach. This approach uses rules to represent known intrusions, which typically match multiple signatures.

These rules are not only specific to known intrusions but can also be tweaked to fit the network, as the same intrusion may leave different evidence in different networks depending on the network setup. Snort is a widely-known example of a rule-based network intrusion detection system.

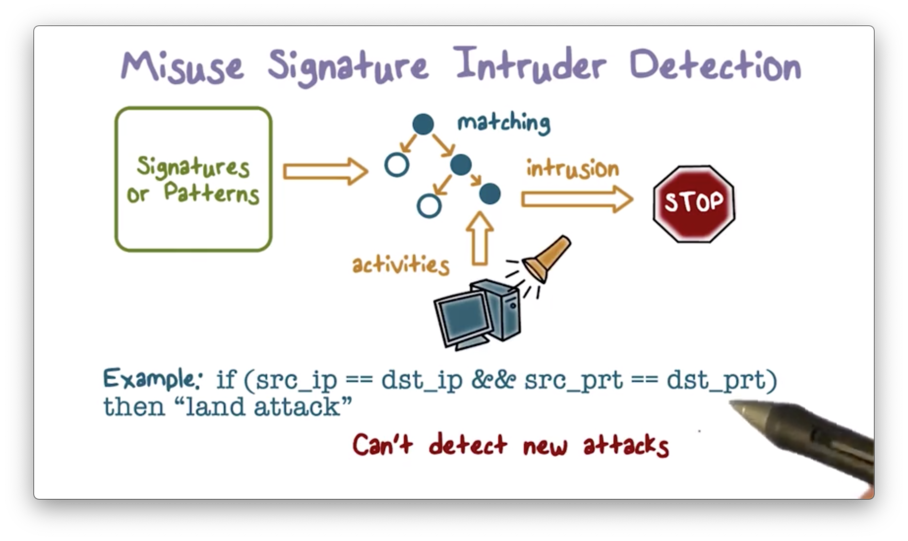

Misuse Signature Intruder Detection

The IDS matches the observed activities using a set of attack signatures or patterns. If there is a match, the IDS outputs an alert.

For example, the system may raise an alarm if it spots the so-called "land attack" defined in the picture above. Again, such a simple approach cannot detect new attacks since they don't have signatures.

Attacks Quiz

Attacks Quiz Solution

Monitoring Networks and Hosts

An IDS typically performs passive monitoring; that is, it records and analyzes data about system and network activities while these activities continue to take place.

The IDS doesn't affect activities directly, but rather only outputs alerts. In response to these alerts, the system can intervene and alter activity by, for example, blocking a network connection or terminating a program.

Network IDS

We can deploy an intrusion detection system at the perimeter of a network or subnet to monitor inbound and outbound network traffic. Such a system is called a network intrusion detection system (NIDS).

NIDS's typically use a packet-capturing tool like libpcap to obtain network traffic data. The captured packet data contains the complete information about network connections; for example, TCP handshake information, as well as all of the URL requests from the client and the returned page contents from the server.

Since a NIDS can see all of the data sent and received by a user's machine, it can raise an alert if it detects something has gone awry. If the user's machine is infected by a bot malware, for example, the NIDS will see attempts to connect to a website for command and control, and it can generate the appropriate alert.

Network Based IDS (NIDS)

A NIDS monitors traffic in real-time or close to real-time so that it can react to intrusions promptly. It can analyze traffic in multiple layers of the network stack, responding to network-, transport-, or application-level protocol activity.

A NIDS can include several sensors, each of which typically monitors the traffic of a subnet and reports its findings to a backend management server. This server correlates evidence across multiple sensors to provide intrusion detection across the whole network.

Additionally, a NIDS may provide one or more management consoles for use by human analysts needing visibility into network activity.

Host IDS

We can also deploy an IDS in an end host. Most host-based IDS's use ptrace to obtain the system calls made by a program as a way to monitor program behavior.

System call data is crucial for security monitoring because the operating system manages critical system resources. Therefore, whenever a program requests a resource, such as memory allocation or access to the filesystems, networks, or I/O devices, it must make a system call to the operating system.

For example, If a user's browser receives a page containing malicious javascript that breaks the protection in the browser and attempts to overwrite a Windows registry file, the IDS will observe a write system call to the registry file and can generate an alert.

NIDS Quiz

NIDS Quiz Solution

Inline Sensors

One way to configure a network IDS is by using inline sensors. The primary motivation for using inline sensors is to enable them to block an attack upon detection. In such cases, an inline sensor performs both intrusion detection and intrusion prevention.

We must place the sensor at a network point where traffic must pass through it for this strategy to be effective. We can deploy an inline sensor as a combination of a network IDS and a firewall in a single piece of hardware, or we can deploy the inline sensor as a standalone inline network IDS.

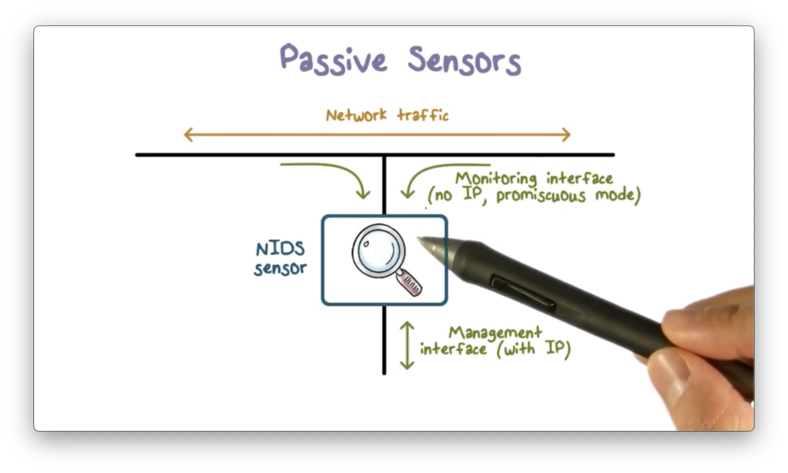

Passive Sensors

More commonly, we deploy network IDS's as passive sensors. A passive sensor only receives a copy of live traffic, and therefore cannot provide any intrusion protection; however, from a network performance perspective, this approach is much more efficient.

The following diagram illustrates a typical passive sensor configuration.

The sensor connects to the network transmission medium, such as an ethernet cable, through a direct physical tap that provides the sensor with a copy of all network traffic carried by the medium.

The network interface card (NIC) for the tap usually does not have an IP address configured for it, which means that the data collection side of the sensor is unreachable outside of the tap. The sensor has a second NIC that connects to the network with an IP address so that it can communicate with one or more backend management servers.

Firewall Versus Network IDS

A network IDS performs passive monitoring. While the IDS is copying and analyzing network traffic, the traffic continues to flow to its destination.

Traffic analysis can take a lot of computing power, and a large volume of traffic can overload an IDS, preventing it from detecting intrusion in a timely manner. We call this situation fail-open, meaning that the network is open to intrusion when the IDS fails.

A firewall performs active filtering. All traffic must pass through the firewall, and the firewall performs relatively simpler and more efficient analysis.

A large volume of traffic can overload a firewall as well. When this happens, it prevents all traffic from passing through. We call this fail-close, meaning that when a firewall fails, the internal network is closed to the external network, and is safe from intrusion.

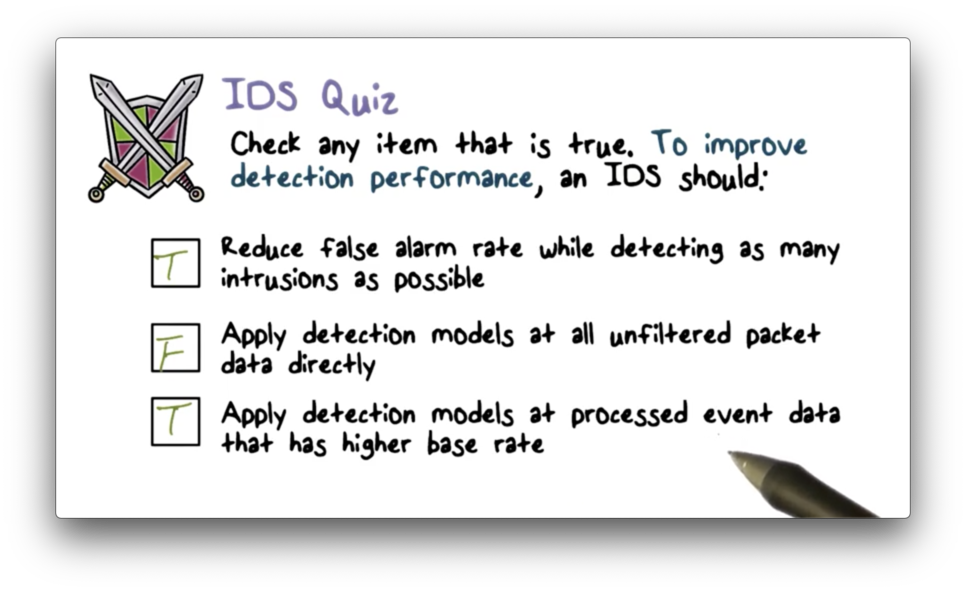

IDS Quiz

IDS Quiz Solution

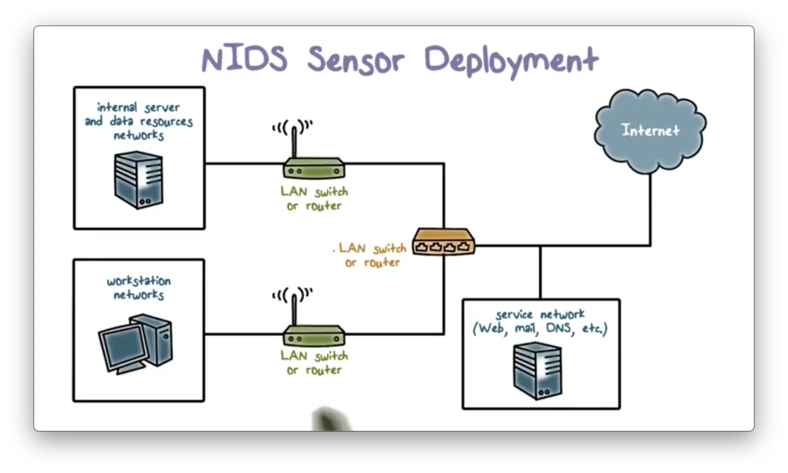

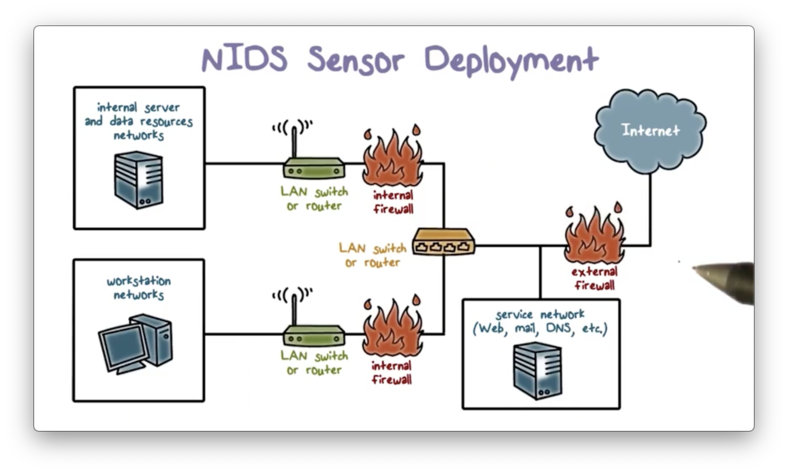

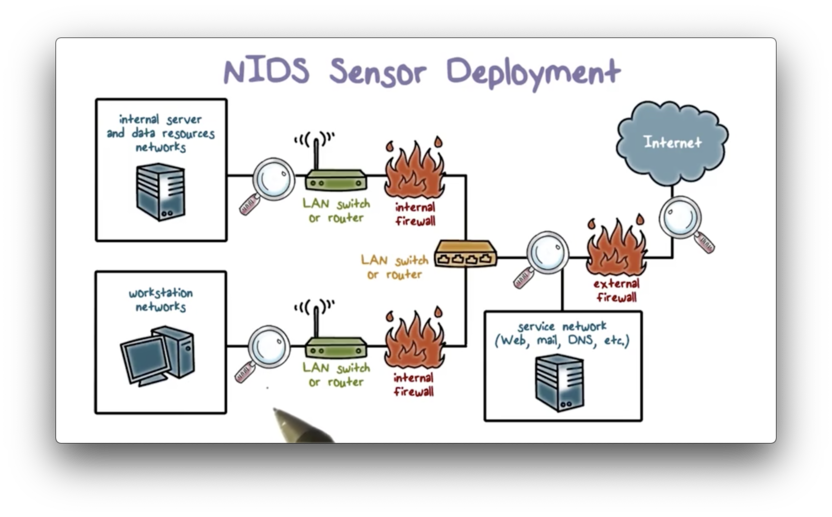

NIDS Sensor Deployment

Here is an example of an enterprise network configuration. The internal network has multiple subnets, and the enterprise has public-facing services, such as a public web server.

Recall our lecture on firewalls. We typically want to place an external firewall to protect the entire enterprise network. Additionally, we want to protect the internal network from the public-facing servers. We place these servers in a DMZ, and we use internal firewalls to monitor traffic between the DMZ and the internal subnets. The internal firewalls also monitor traffic between the subnets.

A common location for an IDS sensor is just inside the external firewall, a position which has several advantages.

An IDS in this position has an excellent vantage point. It can see attacks from the outside world aimed at the internal network as well as the public-facing servers in the DMZ.

Additionally, because the IDS in this position monitors all outgoing traffic across the entire enterprise network, it can also detect attacks originating from a compromised server either in the DMZ or the internal network.

As well, since the IDS sits just inside the external firewall, we can compare the logs of the IDS against the logs of the firewall to see whether the firewall missed an attack it should have prevented.

We can also place our IDS between the external network and the Internet. The main advantage of this location is that the IDS can see all attempted attacks aimed at the enterprise network, including those attacks that might be filtered by the external firewall.

For example, if the external firewall is overloaded, it not only drops incoming attack packets, but it might not even have the resources to log these packets. An IDS at this location can see the packet and log it.

We can also deploy the IDS at a subnet boundary. Compared with the IDS at the perimeter, which has to examine all traffic, an IDS at this location can perform a more detailed analysis of traffic data since it has less traffic to monitor. Additionally, a subnet IDS can detect intrusions from inside the network.

As well as protecting a subnet, an IDS can also protect the workstations or networks of important personnel or departments. An IDS at this location focuses on targeted attacks, such as attacks aimed at financial transaction systems.

Compared with an IDS at the network perimeter, which must examine traffic across the whole network, an IDS at this location can instead focus exclusively on traffic to high-value systems.

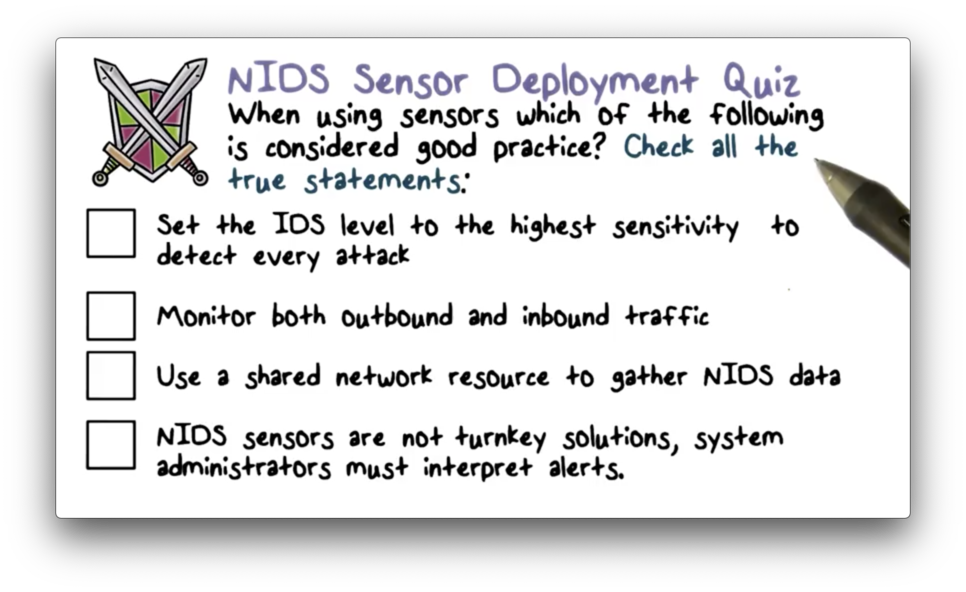

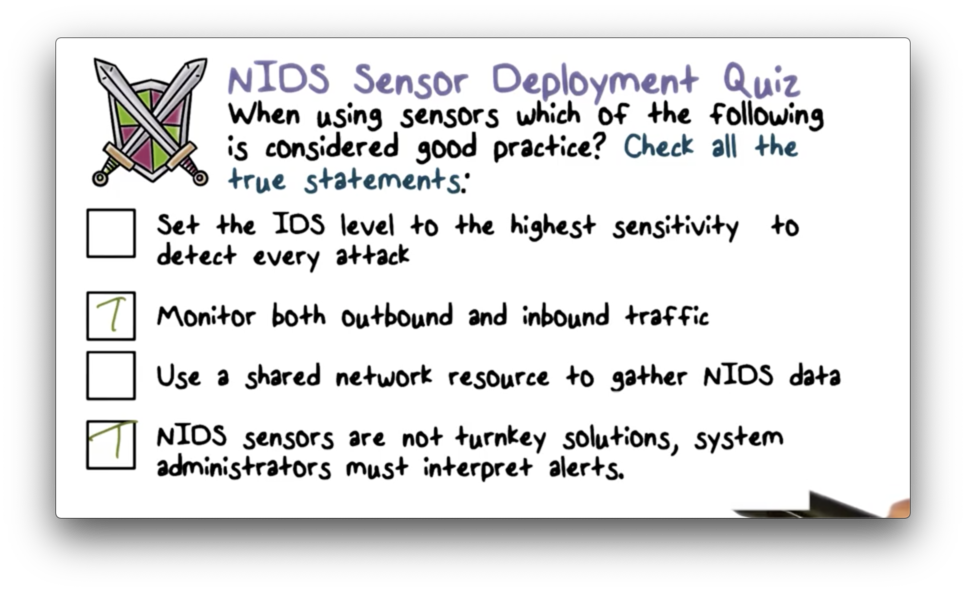

NIDS Sensor Deployment Quiz

NIDS Sensor Deployment Quiz Solution

Snort

Snort is an open-source, easily configurable, lightweight network IDS that can be easily deployed on most nodes of a network, including end hosts, servers, and even routers.

Snort can perform real-time packet capture, protocol analysis, and packet content-searching, and it consumes only a small amount of memory and processor time to perform its tasks.

Snort can detect a variety of intrusions based on the rules configured by a sysadmin. Helpfully, there is a community that maintains an extensive set of Snort rules that can be further configured by sysadmins for the needs of their networks.

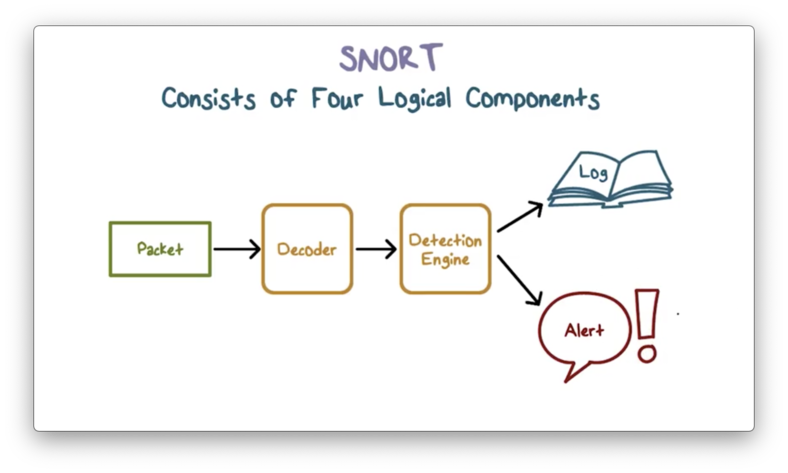

Snort Components

The Snort system has four logical components.

The packet decoder processes each captured packet to identify the protocol headers at the data link, network, transport, and application layers.

The detection engine performs the actual work of intrusion detection and checks each packet against a set of rules to determine if the packet matches a characteristic of a rule. If the engine finds a match, it triggers the action specified by the matching rule or rules; otherwise, it discards the packet.

Each rule specifies what logging or alerting steps the system should take. The logger stores the detected packet in a human-readable format. A sysadmin can then use the log files for later analysis. Alternatively, the system can send alerts to a file, database, or email, among other options.

Snort Configuration

Snort can be configured as inline or passive. In passive mode, it merely copies and monitors traffic, and the traffic does not pass through it directly. In other words, in passive mode, Snort is configured for intrusion detection only.

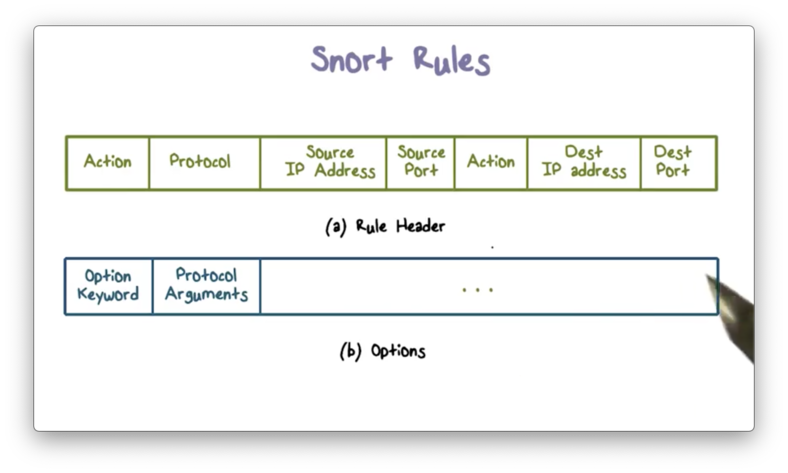

Snort Rules

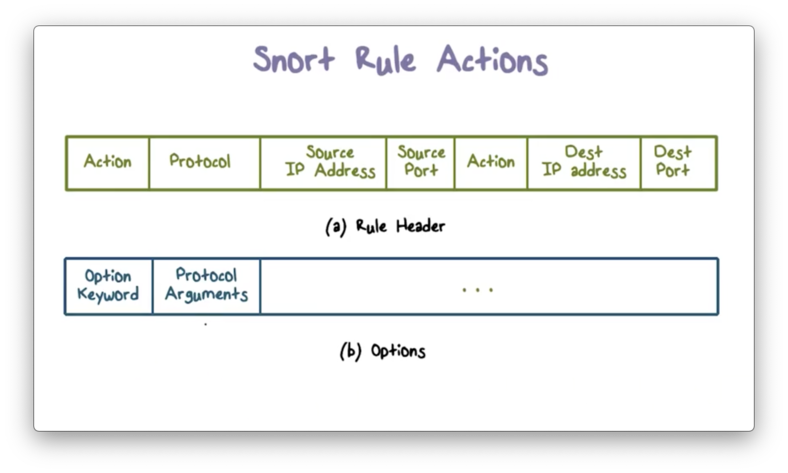

Snort uses a simple and flexible rule definition language. Each rule consists of a row header and a number of options.

Snort Rules Options

We specify our intrusion detection logic in the rule options, of which there are four main categories.

Metadata options allow us to provide information about the rule but do not have any effect on intrusion detection.

We specify the logic to examine the packet payload in the payload options, and we specify the logic to examine the packet headers in the non-payload options.

Post-detection options allow us to specify actions that the system will fire after a match has occurred, such as storing the packet information in a table so that we can correlate it with other packets.

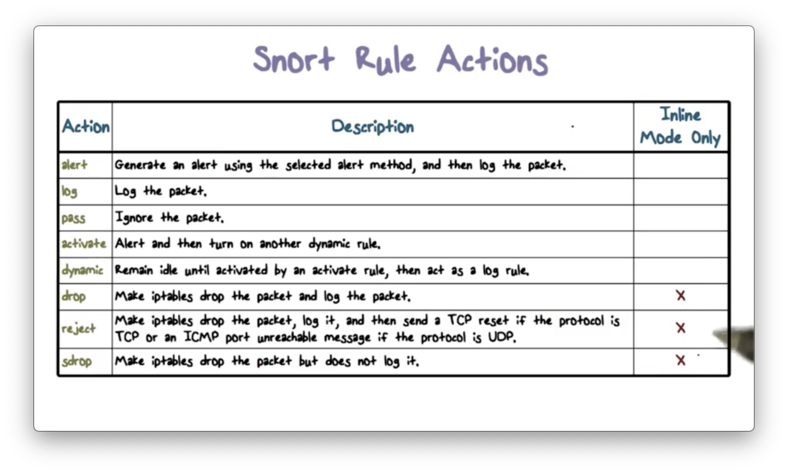

Snort Rule Actions

The most important field in the Snort rule header is the action field, which tells Snort what to do when a packet matches a rule.

The following table describes the possible actions, the last three of which are only available in inline mode.

To summarize, a Snort rule includes a header and multiple options. Each option consists of an option keyword, which defines the option, followed by arguments, which specify the details of the option.

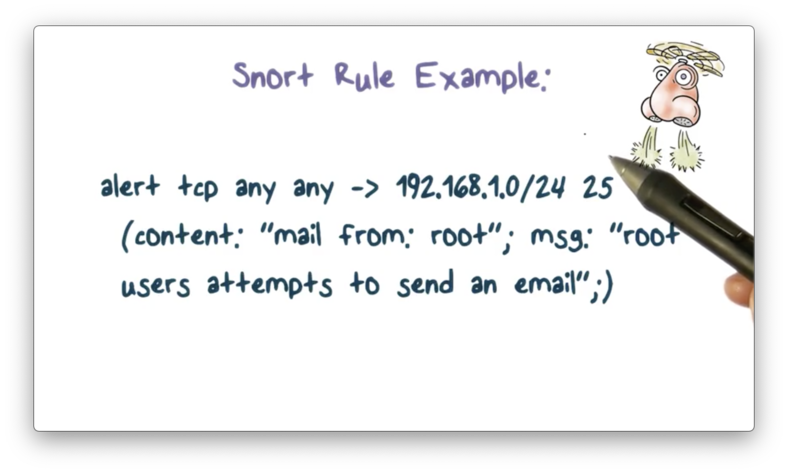

Snort Rule Example

Typically, the root user account is only used for specific privileged operations, such as backing up filesystems and setting up subnetworks. A root account rarely sends email, and such an event should trigger an alert.

Here is an example of how Snort can capture and respond to this event.

It looks for traffic to the SMTP port on any host in the /24 subnet and checks if the content of the email contains "mail from root", which indicates that a root user is attempting to send email. Snort then sends an alert with the following message: "root user attempts to send an email".

The content keyword used above is one of the more important features of Snort. It allows sysadmins to set rules that search for specific content in the packet payload and then trigger responses based on that data.

Snort Quiz

Snort Quiz Solution

Honeypots

Honeypots are another component of the intrusion detection architecture. Honeypots are decoy systems designed to lure attackers away from critical systems.

By diverting attackers from valuable systems to honeypots, we can observe what they are trying to do to our systems and networks. Based on that information, we can develop strategies to respond to their attacks.

A honeypot system gives the appearance that any attack against it is successful. This apparent ease of compromise attracts attackers to a honeypot and keeps them there, which allows us to gather more information about their attacks.

Typically, a honeypot is filled with fabricated information to make it appear as if it is a valuable system on the network. Most importantly, a honeypot is not a real system used by any real user.

A honeypot system is instrumented with monitors and event loggers so that any access to or activity on the honeypot system is logged.

Since a honeypot is not a real system and has no production value, any access to it is not legitimate. Most likely, any inbound connection to a honeypot is a network scan or a direct attack. Any outbound traffic from the honeypot indicates that the system is most likely compromised.

Honeypots Classification

A low interaction honeypot typically emulates some network services, such as the web server, but does not provide a full version of the service. For example, an emulated web server may be able to "speak" HTTP but might not contain all the web contents and server-side programs.

A low interaction honeypot is typically sufficient to detect basic network scans and probes and warn of imminent attacks. On the other hand, these weakly emulated services may not fool a sophisticated attacker, who might realize early on that these services are not real.

A high interaction honeypot essentially replicates a real server or workstation in terms of operating systems, services, and applications. They look realistic, and they can be deployed alongside the real servers and workstations.

Since a high interaction honeypot mimics a system, an attacker might attack it for an extended time without realizing that it is a honeypot. This large attack window gives us more time to learn about the attacks.

On the other hand, making a honeypot look like a real server or workstation is quite challenging. For example, we must emulate user activities and network traffic on the honeypot, which requires a significant amount of programming effort and data storage.

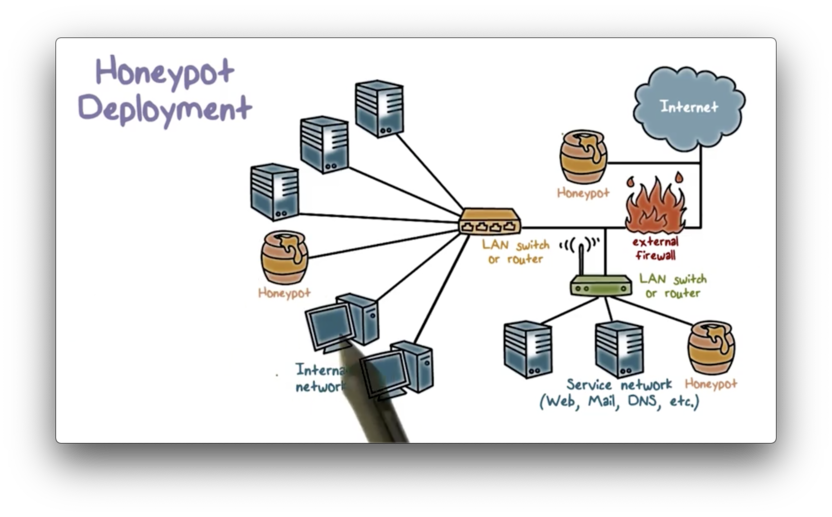

Honeypot Deployment

We can deploy honeypots to a variety of locations within a network.

A honeypot placed outside of the external firewall is useful for checking attempts to scan or attack the internal network. The main advantages of placing the honeypot at this location are that first, it has no side effects, and second, it reduces the amount of attack traffic the firewall has to process. However, a honeypot at this location cannot trap internal attackers.

We can also place a honeypot in the DMZ, alongside public-facing servers, to trap attacks targeted at these services. A honeypot at this location may not be able to trap interesting attacks, because a DMZ is typically not accessible outside of a well-defined set of public-facing services. As a result, the external firewall can block virtually all attack traffic destined for the DMZ.

Finally, we can also place a honeypot in the internal network alongside servers and workstations. The main advantage of this configuration is that it can catch internal attacks. Additionally, it can detect a misconfigured firewall that forwards non-permissible traffic from the Internet to the internal network.

On the other hand, unless we can trap the attacker entirely in the honeypot, the attacker may be able to reach other internal systems.

As well, if we want to continue to attract and trap an attacker, we must continue to allow attack traffic from the Internet to reach the honeypot. This step might involve opening up the external firewall to allow this attack traffic to enter, which carries a considerable security risk.

Honeypot Quiz

Honeypot Quiz Solution

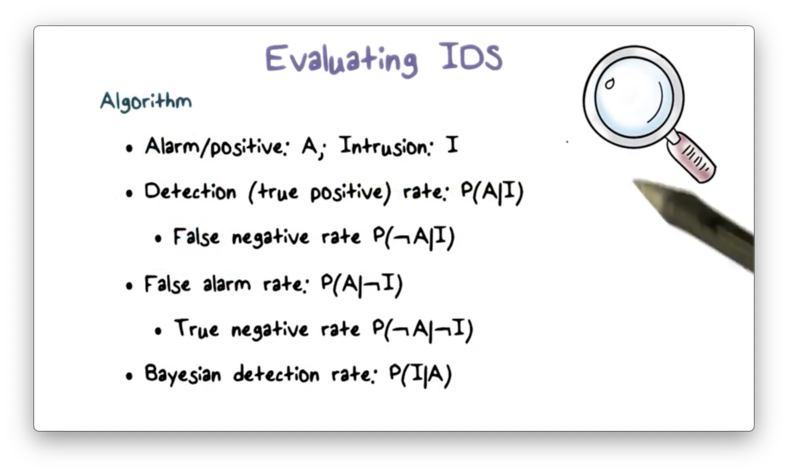

Evaluating IDS

We typically use accuracy metrics to evaluate the detection algorithm. We use detection rate or true positive rate to measure how well an IDS can detect an intrusion. More specifically, the detection rate measures how likely the IDS outputs an alert, given that an intrusion is present. We can also use the false negative rate, the probability that, given an intrusion, an alert is not triggered.

Alternatively, we can look at the false alarm rate. This rate measures the probability that the IDS generates an alert, given that there is no intrusion. We can also use the true negative rate, the probability that an alert is not triggered given an intrusion is not present.

We might also want to know the Bayesian detection rate of an IDS; that is, the probability that an intrusion has occurred, given that an alert is raised.

We can more formally summarize these metrics, using the probability A of an alarm being raised and the probability I of an intrusion occurring.

The detection rate is the probability of A, given I. The false negative rate is the probability of not A, given I. The false alarm rate is the probability of A, given not I. The true negative rate is the probability of not A, given not I. The Bayesian detection rate is the probability of I given A.

In addition to the detection algorithms, we can also evaluate IDS's in terms of their system architecture. We want a scalable IDS that can function in high-speed networks. Additionally, we want a resilient IDS that is not easily disabled by attacks that target the IDS.

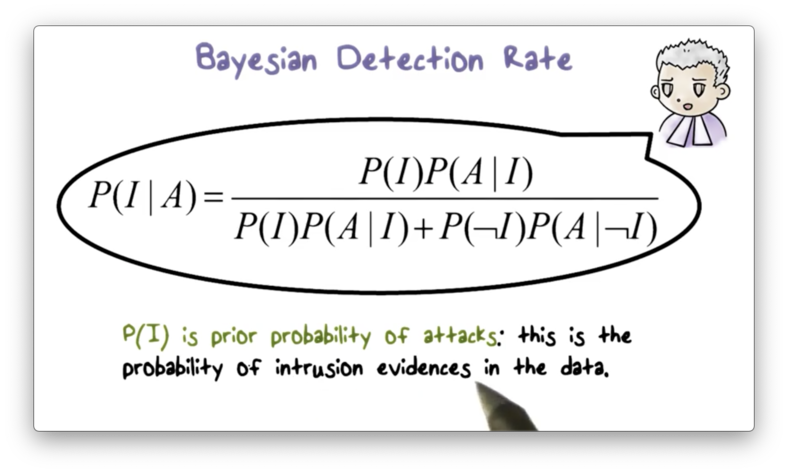

Bayesian Detection Rate

The following formula defines the Bayesian detection rate, given probability A of an alert and prior probability I of an intrusion.

We can calculate I by counting the number of packets that flow through our network during a particular time period and taking the percentage of packets that contain evidence of intrusion activities.

There is an interesting phenomenon involving the Bayesian detection rate, called the base-rate fallacy. The base-rate fallacy states that even if the false alarm rate P(A|¬I) is very low, the Bayesian detection rate P(I|A) is still low if the base-rate P(I) is low.

For example, given a detection rate P(A|I) = 1, a false alarm rate P(A|¬I) = 10^-5, and a base rate of intrusion P(I) = 2 * 10^-5, the Bayesian detection rate P(I|A) is only 66%.

This low base rate may or may not be realistic, depending on where you measure it. For example, tens of millions to hundreds of millions of packets may pass through the entire network, and only a few hundred might contain intrusion activity. Thus, measured from the perspective of the entire network, this base rate can be quite realistic.

One way we can mitigate the base rate fallacy is to reduce the false alarm rate to zero, or as close to zero as possible; indeed, this is one of the main goals of modern IDS vendors.

Alternatively, we can deploy the IDS to the appropriate layer such that, at that layer, the base rate is sufficiently high. Modern-day IDS's use a hierarchical architecture to achieve this high base rate.

We can also use multiple independent models. This approach is similar to medical diagnosis, where multiple tests are used to reduce the overall false positive rate and increase the Bayesian detection rate.

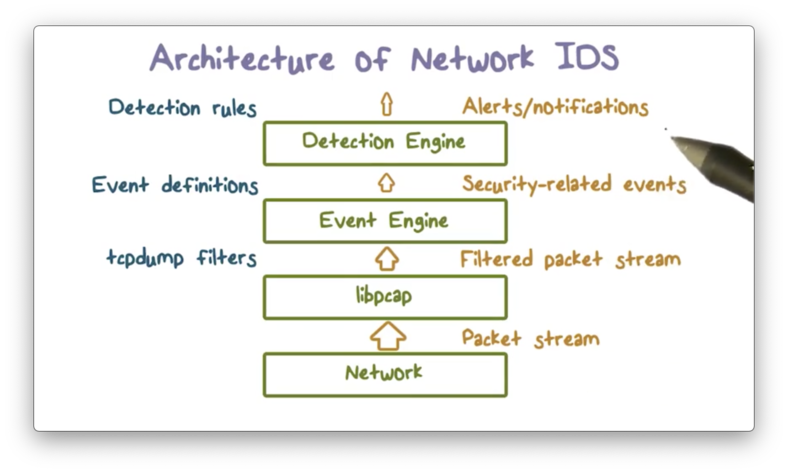

Architecture of Network IDS

With the Bayesian detection rate and the base-rate fallacy in mind, let's discuss the system architecture of a network IDS.

Typically, the volume of packet data in a network is enormous - on the order of tens of millions of packets per day - and only a few might involve any activity related to intrusion. Therefore, according to the base-rate fallacy, if we apply detection algorithms at the packet level, we will see meager Bayesian detection rates.

Instead, we should apply detection models to a set of data that has a higher base rate, which requires that we filter out packet data unlikely to be related to intrusion activity.

First, we can apply filters to the packet data by, for example, instructing libpcap to only capture packets destined for certain services. Second, an event engine analyzes the filtered packet data and summarizes them into security-related events, such as failed logins. Finally, the system applies detection models to the data contained in each security-related event.

The system decreases the volume of packet data at each step. Therefore, as long as we capture the intrusion evidence in the event data, the base rate is going to be much higher because the total number of packets is going to be much lower. As a result, the IDS model applied to the event data will yield a higher Bayesian detection rate.

IDS Quiz

IDS Quiz Solution

Eluding Network IDS

Now let's talk about how an attacker can evade an IDS so that their attack can proceed undetected.

Recall that a network IDS performs passive monitoring; that is, it takes a copy of the network traffic destined for the end host and analyzes it. Therefore, for the IDS to detect the intrusion happening at the end host, it must see the same traffic as the end host.

However, this parity is not always present, and an attacker can exploit this to evade the IDS. The reason that the IDS and the end host see different traffic is because they are using two different operating systems that process traffic in different ways.

In particular, TCP/IP protocol specifications have ambiguities that lead to different implementations in different operating systems. As a result, an IDS running on Unix and an end host running on Windows may not process certain packets in precisely the same fashion.

For example, options such as time-to-live (TTL), or error conditions associated with fragments and checksums are handled in different ways in different operating systems.

By exploiting these differences, the attacker can slip attack traffic past the IDS undetected while still impacting the destination end host.

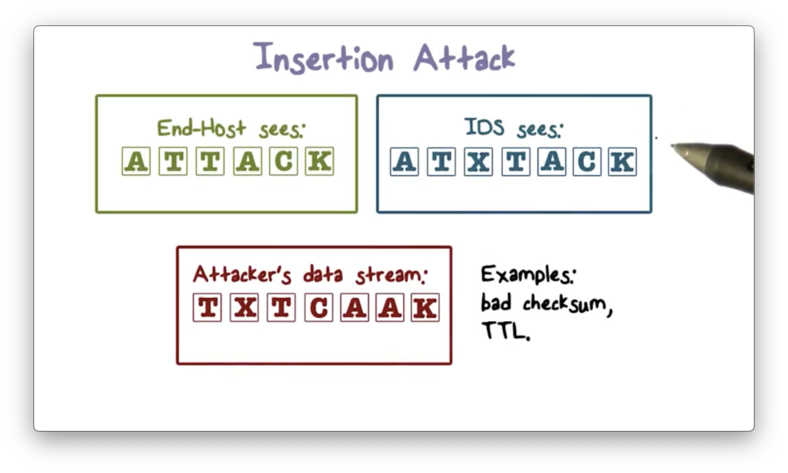

Insertion Attack

An attacker can insert misleading data into the packet stream to cause the IDS to miss an attack. For example, an attacker might include a packet with a bad checksum value into an otherwise malicious stream of packets. The IDS may accept this packet, but the end host might reject it. As a result, the end host receives the attack, and yet the IDS doesn't detect it.

Here is an illustration of this insertion attack.

The attacker sends the out-of-order packets that both the IDS and the end host reassemble according to sequence numbers. One of the packets X has a bad checksum value. The IDS accepts X, and sees the packet stream ATXTACK, which looks benign. On the other hand, the end host rejects X and, as a result, sees the ATTACK.

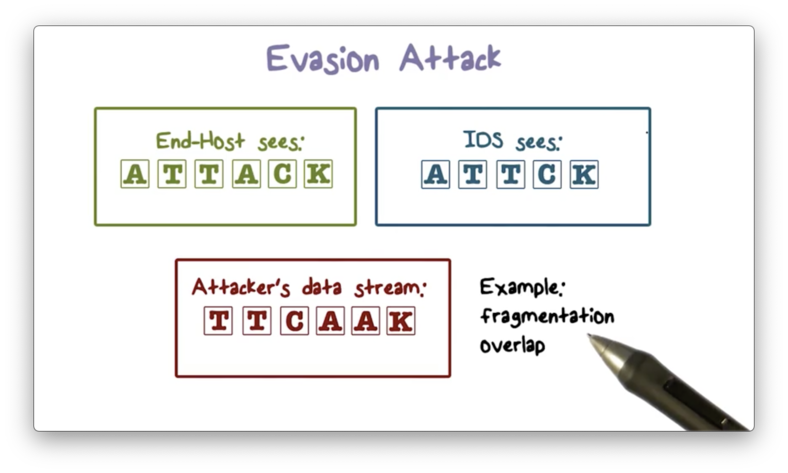

Evasion Attack

The attacker can also hide part of the attack to evade IDS detection. An IDS may discard a packet fragment that overlaps with a previous fragment, but an end host may accept both fragments. Therefore, an attacker can send an attack embedded in overlapping packet fragments through the IDS to the end host.

Here is an illustration of this evasion attack.

The attacker sends the out-of-order packets that both the IDS and the end host reassemble according to sequence numbers. In this scenario, the two A's contain overlapping fragments; as a result, the IDS drops the second A, and so it only sees the stream ATTCK. On the other hand, the end host accepts both fragments, even though they overlap. Therefore, the end host sees the ATTACK.

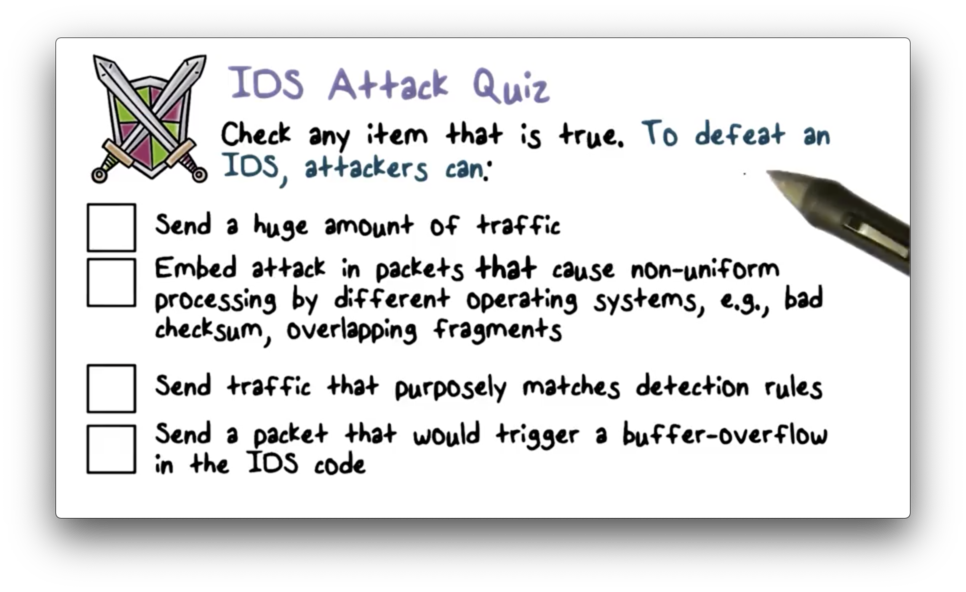

DOS Attacks on Network IDS

Attackers can also use denial of service (DOS) attacks to disrupt the network intrusion detection process. Similar to DOSing a network server, an attacker can send a lot of traffic to an IDS to process, which results in the exhaustion of resources such as CPU, memory, and network bandwidth.

As a result, the IDS may not be able to analyze subsequent traffic, and such traffic may contain actual attacks. Knowing this, the attacker can first disable the IDS through a DOS attack and then launch the real attack.

Another attack approach involves abusing the reactive nature of intrusion detection. When the IDS outputs an alert, a security admin must analyze the alert. Therefore, the attacker can overload the system by sending a lot of traffic that triggers alerts; for example, purposely crafting and sending packets that contain signatures of attacks.

The goal with this attack is first to overwhelm the response system and the security admins and then send the real attack traffic. The attack traffic will generate an alert but, because the security admins are busy analyzing alerts of fake attacks, the alert will not be analyzed until it is too late.

Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS)

In addition to intrusion detection systems, there are also intrusion prevention systems (IPS) on the market. Instead of merely sending alerts like an IDS, an IPS tries to block an attack when it detects malicious activity.

Similar to an IDS, an IPS can be deployed at the end host, the network perimeter, or some combination of different locations depending on network needs.

An IPS also uses similar detection algorithms as an IDS. For example, it can use anomaly detection algorithms to detect abnormal behavior and then stop such behavior.

The main difference between an IPS and a firewall is that while a firewall typically only uses simple signatures of attacks to block traffic, an IPS can use very sophisticated detection algorithms.

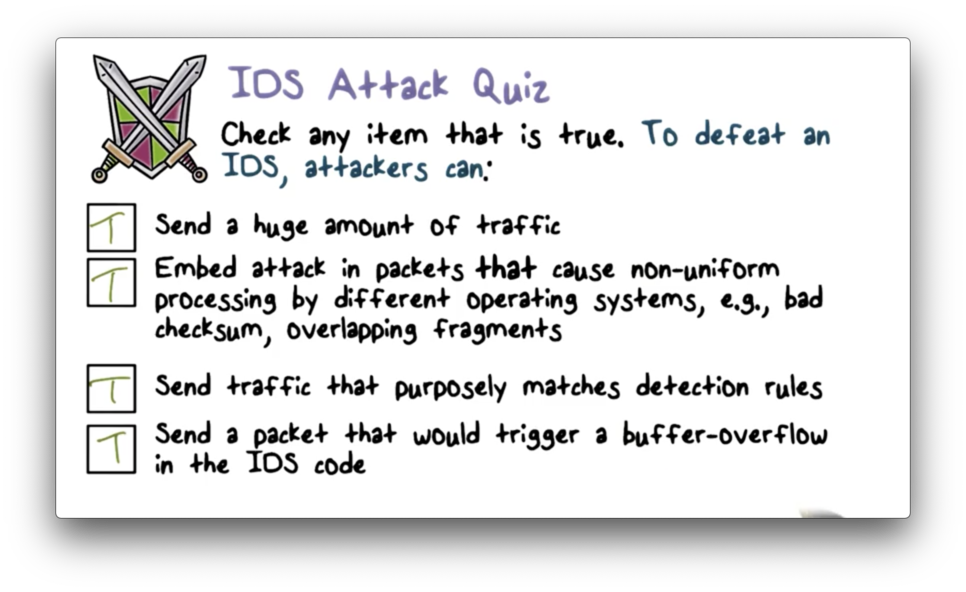

IDS Attack Quiz

IDS Attack Quiz Solution

Last updated