Firewalls

Defense in Depth

When it comes to defense against attacks, the most important principle is to employ defense in depth. In other words, we should utilize multiple layers of defense mechanisms.

The first line of defense is prevention: prevention stops attacks from getting into our networks and systems in the first place. Inevitably though, some attacks will defeat the prevention mechanism. For example, anti-virus software may not prevent a user from downloading a Trojan horse, since Trojan horses appear to be legitimate programs.

Detection and response mechanisms make up the second line of defense. These mechanisms monitor activities in our systems and networks to detect attacks and repair damage. Just like with prevention, there will be attacks that can go undetected, at least until they have inflicted their damage. For example, the APT malware examples we discussed previously are often hard to detect because they blend in with normal activities so well.

The third line of defense consists of the attack-resilient technologies that enable the most valuable system components to survive attacks. For example, a server is a collection of diversified subsystems with different implementations. At least one of these subsystems will not be susceptible to an attack since an attack typically exploits specific vulnerabilities that may be present on some, but not all, components.

What is a Firewall?

To motivate the need for firewalls, let's first take a high-level tour of a typical enterprise network.

An enterprise network is part of the Internet. It typically has an internal, trusted intranet that only the employees can access. At a bank, for example, the trusted part of the network holds the internal email server and the systems that process financial transactions.

The enterprise network can also have a public-facing part. A bank may have a web portal where customers can log in and view their account. These public servers live in the so-called demilitarized zone (DMZ), which is a part of the enterprise network that is separated from the trusted network. While customers can interact with the webserver to log in and submit transaction requests, they cannot directly access the servers in the trusted network that are authorizing and processing transactions.

When a company has multiple physical sites, each site can have its own local, trusted network. However, these sites will need to communicate with one another. For example, employees in one bank branch may need to access the corporate network at the headquarters in another city. Such access must take place using the untrusted Internet.

We use routers to get traffic to its destination correctly across the Internet. Each local network has at least one router at its perimeter and these routers together with the core routers in the Internet backbone transport packets from one local area network to another.

While routers can send this traffic, the network needs to decide whether it should allow such traffic, based on security considerations. For example, the bank may want to explicitly disallow any external traffic from reaching the trusted network directly.

A firewall is a device that provides secure connectivity between networks. It is used to implement and enforce a security policy for communication between the networks.

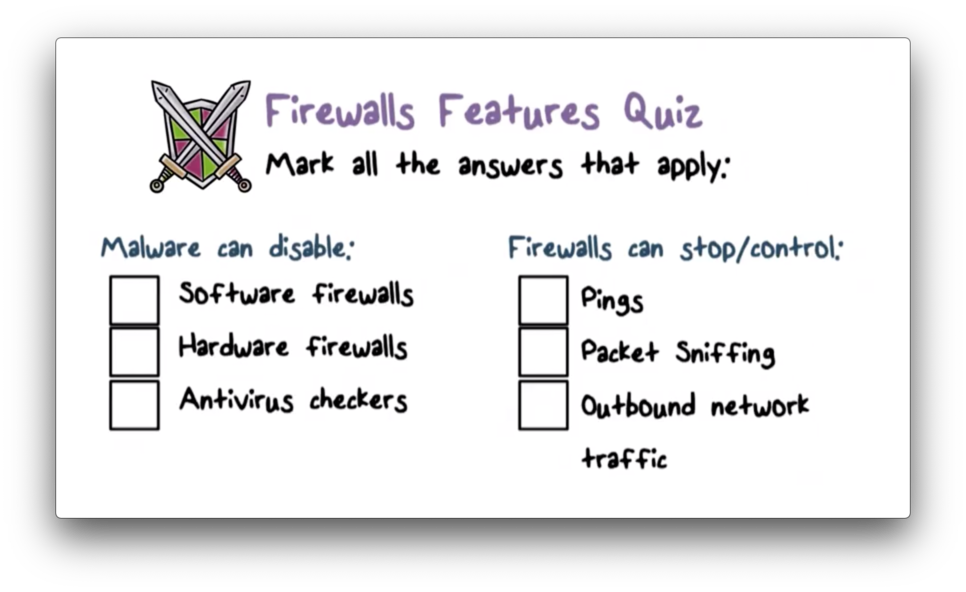

Firewalls Quiz

Firewalls Quiz Solution

Firewall Design Goals

A firewall is designed to enforce security policies on inbound and outbound network traffic. All traffic must be checked at the firewall, and only traffic that has been authorized by the security policy is allowed to pass through.

In addition to correctly enforcing the security policies, a firewall must also be dependable. This means that the firewall must not be easily crashed or disabled by an attack. A disabled firewall can no longer enforce the security policies of the network.

Firewall Access Policy

A critical component in the planning and implementation of a firewall is defining a suitable access policy. A network access policy specifies the types of traffic that are authorized to pass through the firewall. Traffic can be authorized using many different criteria, including address ranges, protocols, applications, and content types.

Policies should be developed through a security risk assessment conducted by the organization. This assessment will reveal what types of traffic the organization must support and what security risks are associated with this traffic, which will inform the firewall implementation.

Firewall Limitations

A firewall cannot provide protection against traffic that does not flow through it, such as traffic that is routed around it or traffic that is internal to the network. Additionally, if a firewall is misconfigured, it may not properly enforce the security policy against the traffic that it sees.

Additional Convenient Firewall Features

A firewall can log all traffic that passes through it, and the log can be analyzed later to learn more about the traffic, such as the traffic volume to a specific part of the network.

Firewalls can also provide network address translation. This is useful when multiple machines in the internal network have to share a single public IP address. For outbound traffic leaving the network, the firewall rewrites the local source IP address of a packet coming from an internal host to the public IP address. For inbound traffic, the firewall translates the destination IP address of the packet from the public IP address to the local IP address of the internal host.

A firewall can also provide encryption services. Two trusted networks may choose to send encrypted traffic to one another as a way to ensure that their communication cannot be eavesdropped on by other untrusted networks on the Internet.

Firewall Features Quiz

Firewall Features Quiz Solution

Firewalls and Filtering

The main mechanism in firewalls is traffic filtering. The firewall stops each packet - whether inbound or outbound - and checks it against the security policy. After performing the check, the firewall will decide whether to allow or discard the packet.

Filtering Types

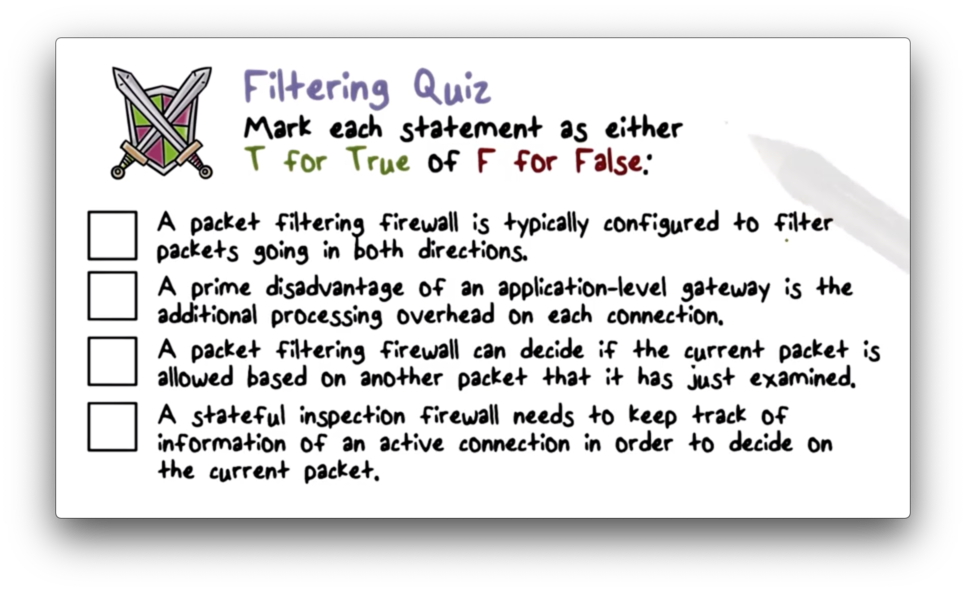

There are two main types of filtering: packet filtering and session filtering. In packet filtering, the firewall examines each packet by itself, and forwards or rejects the packet based on its attributes. In session filtering, a packet is examined within the context of a session. A firewall must maintain some additional state about each connection it receives to perform this type of higher-level filtering.

Packet Filtering

A packet-filtering firewall makes decisions on a per-packet basis. Since no other information is needed besides the current packet, the firewall does not have to maintain any state information about other packets it has seen. Packet-filtering firewalls are the simplest and most efficient firewalls, but they are not robust against attacks that span multiple packets, especially when each packet by itself is not indicative of an attack.

Packet Filtering Firewall

A packet-filtering firewall is typically set up as a list of rules, where each rule maps one or more packet attributes to an action. The attributes are used to match incoming TCP/IP packet header fields and the actions are typically either forward or discard.

The firewall may define rules that look at many different packet headers. For example, the firewall might inspect the source and/or destination IP address of the packet. Additionally, the firewall may look at the source and/or destination transport-level address (port number). The firewall may also take the IP protocol field - whether TCP, UDP or ICMP - into account.

A firewall with multiple interfaces may also match packets based on which interface the packet was received on or which interface the packet is being sent to. This approach is useful when there are multiple ports in an enterprise network that require multiple security policies.

If a packet doesn't match any of the rules defined in the firewall, then a default action must be taken. There are two default policies: the default discard policy and the default forward policy.

The default discard policy says that if no rule matches the packet, then the packet will be discarded. This is a more secure policy because it provides more control over the traffic that is allowed in the network. However, it can be a hindrance to users who wish to engage with new network services and must tell the sysadmin to enable such traffic.

The default forward policy says that if no rule matches the packet, the packet should be forwarded. Compared with the default discard policy, this policy is more user-friendly, albeit less secure. The security admin must react to each new security threat and add the appropriate rules to the firewall if they choose to use this policy.

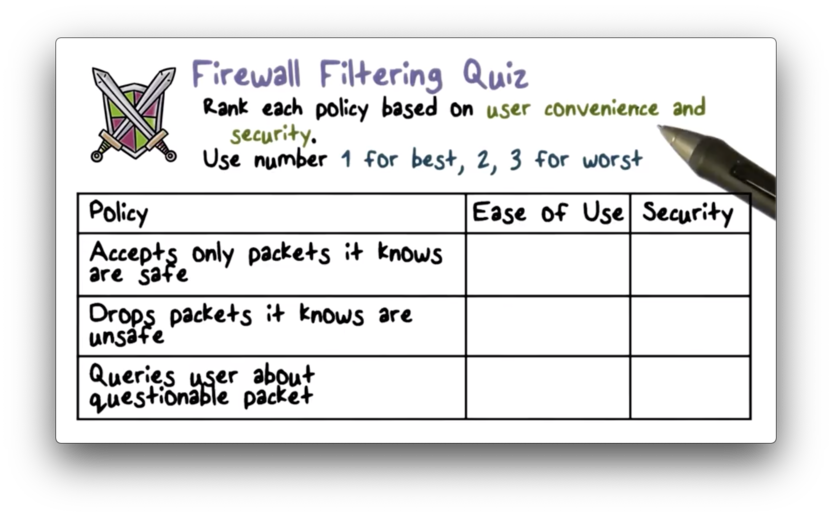

Firewall Filtering Quiz

Firewall Filtering Quiz Solution

The first example follows the "default drop" rule, which is high security but requires new services to be expressly allowed. The second example follows the "default forward" rule, which is easier to use at the expense of security. The final approach sits in between the two in terms of security and ease of use.

Typical Firewall Configuration

Most standard applications that run on top of TCP follow a client-server model. The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), for example, allows client systems to send email to server systems. The client generates new email messages, typically from user input, and the server accepts incoming messages and places them in the appropriate user mailboxes.

SMTP operates by setting up a TCP connection between the client and the server, in which the server uses port 25 and the client uses any port between 1024 and 65535.

The port numbers below 1024 are the well-known port numbers and are assigned permanently to common applications, such as port 25 for SMTP and port 80 for HTTP. The port numbers between 1024 and 65535 are generated dynamically and have temporary significance only for the duration of the TCP connection from the client to the server.

A packet-filtering firewall that wants to support clients of well-known services must permit inbound network traffic on all these high-numbered ports for TCP-based connections. A firewall that wants to support servers of well-known services must permit inbound network traffic on the well-known port or port ranges associated with those services.

Packet Filtering Examples

Let's look at a simplified rule set for SMTP traffic where the goal is to allow only inbound and outbound email traffic while denying all other traffic.

The rules described here are applied top to bottom for each packet until there is a match.

The first two rules are required to permit SMTP traffic to flow between an external host and an internal provider. Rule one allows inbound SMTP traffic from an external client. Rule two allows outbound traffic over higher-numbered ports. In other words, the first rule allows the external client to make an SMTP request, and the second rule allows the internal server to respond.

Rules three and four are required to permit SMTP traffic to flow between an internal host and an external provider. Rule three allows outbound SMTP traffic from an internal client. Rule four allows inbound traffic over higher-numbered ports. In other words, the third rule allows the internal client to make an SMTP request, and the fourth rule allows the external server to respond.

The final rule is an explicit statement of the default policy, which is to deny packets that don't match any of the previous rules.

Modifying the Rules on Source Ports

There are several problems with the ruleset shown above. For example, rule four allows inbound traffic to any destination port above 1023, whereas the original intent is to only allow inbound traffic that is part of an established SMTP connection. We can make our forwarding rules less permissive by looking at the source port in addition to the destination port.

Now rule four only allows incoming traffic to high-numbered ports if that source port for that traffic is 25; that is, incoming connections are only allowed from mail servers.

We can make these rules even more precise. When a TCP connection is established, the ACK bit is set on the packet header. Because the intent of rule four is to allow inbound SMTP traffic that is part of an established connection, we can check that this bit is set before forwarding the packet.

Packet Filtering Advantages

The main advantage of packet-filtering firewalls is their simplicity and ease of implementation. Packet-filtering firewalls are also very efficient and impose very little overhead. Finally, the rules for packet-filtering firewalls can be very general, since they don't have to take higher-level applications into account.

Packet Filtering Weaknesses

Since packet-filtering firewalls do not examine upper-layer application data, they cannot prevent attacks that exploit application-specific vulnerabilities. If a packet-filtering firewall allows traffic to a given application, it allows all traffic to flow to that application indiscriminately.

Additionally, the logging capabilities of packet-filtering firewalls are limited. A firewall cannot log information about packet data that it doesn't examine. For example, a firewall may allow FTP traffic over port 21, and it may log the presence of FTP traffic, but it cannot log the actual FTP data, such as which files are being transmitted.

Since packet-filtering firewalls make decisions on a per-packet basis, they can't defend against attacks that span multiple packets.

Finally, our SMTP example shows that packet-filtering rules tend to have a small number of conditions, which may be too permissive. An attacker might craft traffic that exploits these misconfigurations.

Packet Filtering Firewall Countermeasures

Let's discuss some attacks on packet-filtering firewalls and the appropriate countermeasures.

In a source IP address spoofing attack, the attacker sends packets from an outside host but with a falsified source IP address matching an internal host. Since firewalls are typically configured to forward traffic from one internal host to another, the attacker hopes that using a spoofed internal source IP address will make untrusted external traffic look like safe internal traffic.

To counter this attack, the firewall must discard all packets with an internal source IP address that arrive on an external interface. This countermeasure is often implemented at the router external to the firewall.

In a source routing attack, an attacker specifies the route a packet should take as it crosses the Internet. The hacker hopes that their selected route will bypass security measures and checks along the way. The countermeasure for this attack is to configure the firewall or router to discard all packets that use this option.

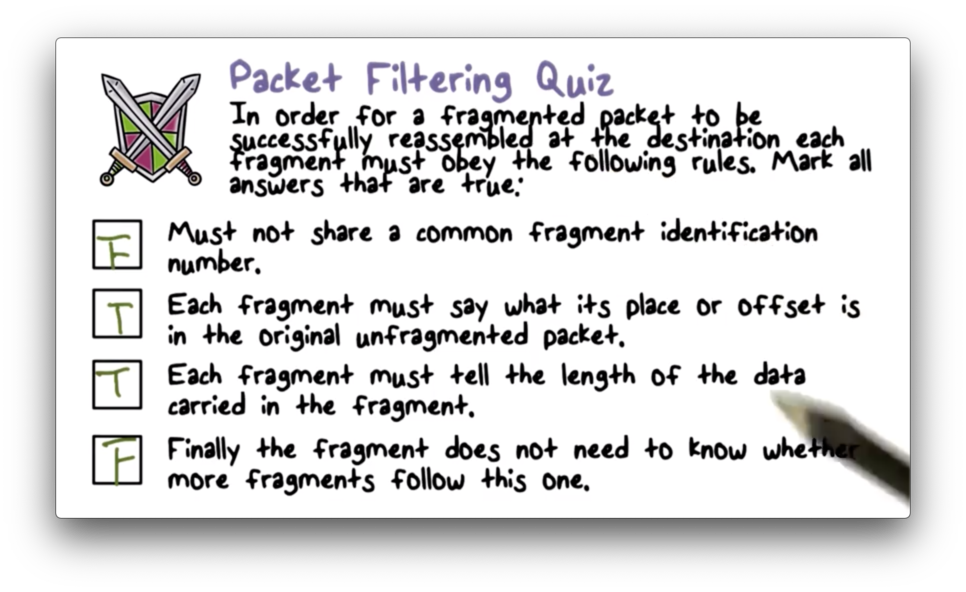

In a tiny fragment attack, the attacker uses IP fragmentation to create extremely small packet fragments and then splits the TCP header information across separate fragments. This attack is designed to circumvent filtering rules that depend on TCP header information.

Typically, a packet filter will make decisions based on the first fragment of a packet. The attacker hopes that the firewall only examines the first fragment and that the remaining fragments - containing header information that would normally cause a packet to be dropped - are passed through.

This attack can be defeated by forcing the first fragment of a packet to contain a predefined minimum amount of transport header information. If the first fragment is rejected, all of the subsequent fragments should also be rejected.

Packet Filtering Quiz

Packet Filtering Quiz Solution

Stateful Inspection Firewall

In a stateful inspection firewall, a packet is analyzed within a larger context. This context often consists of the other packets present in the TCP connection through which the packet is transmitted.

To evaluate an incoming packet within this context, the firewall must record and maintain information about active connections. When a new packet arrives, the firewall updates the information about the connection accordingly and then decides whether the packet should be forwarded based on this context.

A stateful firewall can have a much higher-level view of traffic than a packet-filtering firewall. For example, it may be able to tell that an inbound SMTP packet is a response to a previously outbound packet. Additionally, it can reassemble multiple packets of a connection and inspect the application data, such as the names of files being transmitted during an FTP session.

Connection State Table

Here is an example of a connection table.

The firewall may maintain internal data structures that are linked to the connection table. For example, the HTTP response of a web server serving a page can span multiple packets, so the firewall might maintain a data structure that keeps track of the HTML that it has already delivered. This data structure will allow the firewall to perform a more specific analysis of the connection.

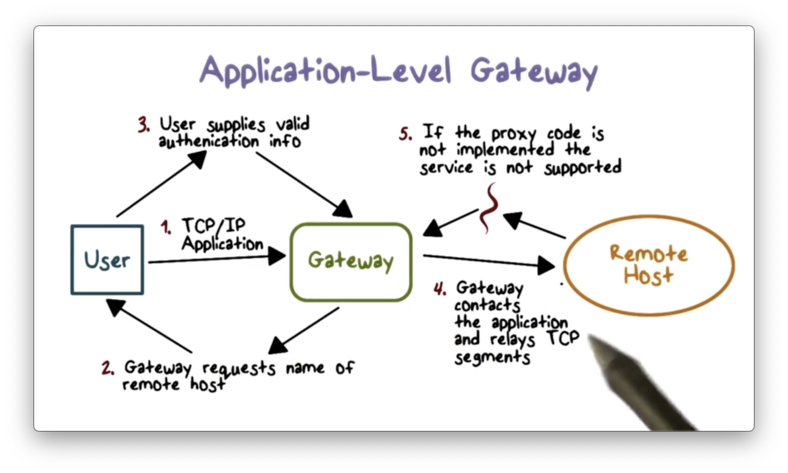

Application Level Gateway

An application-level gateway also referred to as an application proxy, is an application-specific firewall that essentially acts as a relay of application-level traffic. From the perspective of an internal client, the gateway is the external server. From the perspective of the external server, the gateway is the internal client.

To use an application proxy, a user first contacts the gateway using an application protocol such as FTP or HTTP. The gateway then asks the user for the name of the remote server, and the user responds with authentication information which the gateway relays. When the server responds, the gateway will analyze the response and potentially deliver it to the user.

The gateway must implement the correct application logic to correctly analyze the server response. For example, if the gateway is proxying web traffic, it must be able to process HTTP responses just like a web browser.

The advantage of using an application proxy is that we can restrict certain application features. For example, a web proxy can prevent active scripts in web pages by removing them from the HTML returned by the remote server. Since application proxies have more application-specific context than packet filters, they tend to be more secure.

The main disadvantage of proxies is that they incur additional overhead since they must examine and forward all traffic in both directions between the client and server. Additionally, we must install or write proxying code for each application we want to protect.

Filtering Quiz

Filtering Quiz Solution

Bastion Hosts

Application-level gateways typically reside on a dedicated machine called a bastion host. These machines are made to be very secure.

Bastion hosts execute a secure version of the operating system and are configured to allow only essential network traffic, such as web and DNS traffic. Additionally, they can require user authentication, even for traffic originating from an internal host.

Each proxy running on the bastion host is configured to allow access only to specific host systems on the internal network. This configuration ensures that compromised proxies don't lead to attacks on the entire internal network.

Each proxy module installed on the bastion host is a very small software package designed with simplicity and security in mind. For example, a typical Unix email application may contain over 100,000 lines of code while an email proxy might contain fewer than 1,000.

A proxy typically performs no disk access other than reading its initial configuration file. This makes it difficult for an attacker to install a Trojan horse on the bastion host and affect the proxy.

Finally, each proxy typically runs as a non-privileged user in a private, secure directory on the bastion host. If a proxy is compromised during an attack, it cannot easily compromise the entire bastion host or affect other proxies.

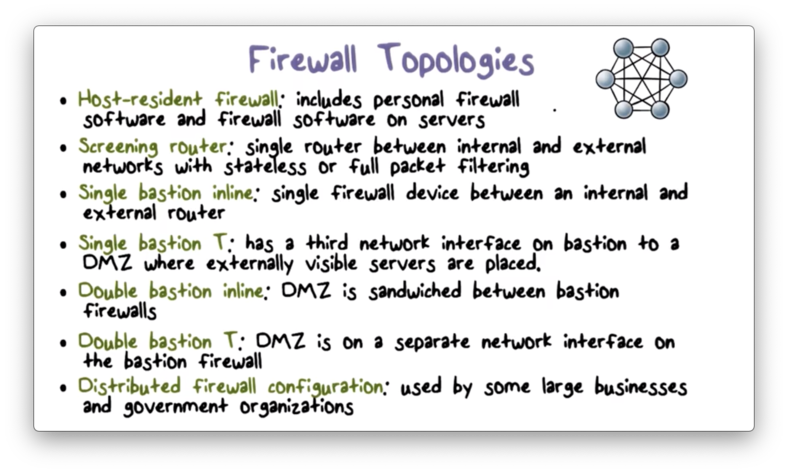

Host Based Firewalls

While firewalls are typically installed at network perimeters, host-based firewalls can be used to enforce a host-specific security policy. Similar to a network firewall, a host-based firewall is a software module used to filter and restrict inbound and outbound traffic. Host-based firewalls are commonly installed on important internal servers.

Host Based Firewall Advantages

There are several advantages to host-based firewalls. First, since these firewalls are host-specific, each instance can implement filtering rules that are tailored to the application it protects. Second, a host-based firewall can stop both internal and external attacks, while a perimeter-resident firewall can only protect against external attacks.

We typically deploy host-based firewalls in addition to network firewalls to provide an additional layer of protection.

Personal Firewalls

Personal firewalls are often deployed at home routers to protect home networks. These firewalls tend to be simpler than host-based firewalls or network-perimeter firewalls because home networks are often less complex than enterprise networks.

The main goal of the personal firewall is to protect the computers in the home network. For example, it can detect and block incoming remote access attempts and outgoing connections to external servers that are known for performing botnet C&C. Therefore, even when a home computer has been compromised, it cannot participate in malicious activities.

Here are some of the common network services that are typically blocked by a personal firewall. A user may configure the firewall to allow one or more of these services if desired.

Advanced Firewall Protection

Besides disabling and enabling certain services, personal firewalls can also provide advanced features.

A firewall can be configured to operate in "stealth mode": dropping all unsolicited packets it receives from the Internet to hide the system(s) behind it.

A user can configure the firewall to drop all UDP and ICMP packets and only accept TCP packets to certain ports.

Additionally, most firewalls have logging capabilities and they can record all unwanted traffic and activities.

Finally, a user might be able to configure the firewall to only allow certain applications - such as those signed by public keys issued by a valid certificate authority - to accept connections from the Internet.

Personal Firewalls Quiz

Personal Firewalls Quiz Solution

If the device is not always protected by the corporate network, as is the case in scenarios 1 and 3, then the personal firewall is needed for additional security.

Deploying Firewalls

The figure below illustrates a common firewall configuration used by enterprise networks.

An external firewall is placed at the edge of the local area network, just inside of the boundary router that connects the corporate network to the Internet. Additionally, one or more internal firewalls protect the bulk of the enterprise network.

Between the internal firewall and the external firewall is a network known as a demilitarized zone (DMZ). Systems that require external connectivity but need some protections are typically located in the DMZ, such as corporate web, email, and DNS servers.

The external firewall provides some basic, first-line defense, while still allowing public access to systems in the DMZ. The internal firewall provides additional protection; in particular, it protects the internal trusted network from less-trusted traffic originating in the DMZ.

Internal Firewalls

Compared with the external firewall in the diagram above, the internal firewall performs more stringent filtering. This is because the internal network requires more protection than the public-facing systems in the DMZ.

The internal firewall protects the remainder of the enterprise network from attacks launched from the DMZ. For example, if a public-facing web server is compromised, the internal firewall can block attack traffic originating from that server.

Additionally, the internal firewall controls access to the DMZ from the internal network. Only authorized traffic from the internal network can reach the DMZ to change, say, a setting on a public-facing web server. For example, such traffic may be limited to having a source IP address of a sysadmin's workstation.

Multiple internal firewalls can be used to protect different parts of the internal network from each other; that is, even if one part of the internal network has been compromised, the other parts are still being protected by their local firewalls.

Distributed Firewall Deployment

A distributed firewall configuration typically includes standalone network firewalls, host-based firewalls, and personal firewalls.

The standalone network firewalls protect the internal network from attacks from the Internet. Additionally, host-based firewalls protect against internal attacks and provide protection tailored to specific machines and server applications. Finally, personal firewalls protect personal computers regardless of where they are in the network.

Security administrators may aggregate and analyze logs from all of the firewalls in the network to get a high-level view of network traffic and compromise. For example, if admins see that multiple host-based firewalls are logging the same attack, they may conclude that a worm is spreading inside the internal network.

Firewall Deployment Quiz

Firewall Deployment Quiz Solution

Stand Alone Firewall Quiz

Stand Alone Firewall Quiz Solution

Firewall Topologies

Last updated