Processes and Process Management

What is a Process?

One of the roles of the operating system is to manage the hardware on behalf of applications. When an application is stored on disk, it is static. Once an application is launched, it is loaded into memory and starts executing; it becomes a process. A process is an active entity.

If the same program is launched more than once, multiple processes will be created. They will have the same instructions, but very different state.

A process represents the active state of an application. It may not be running at every given moment, but it is application that has been loaded and started.

What Does a Process Look Like?

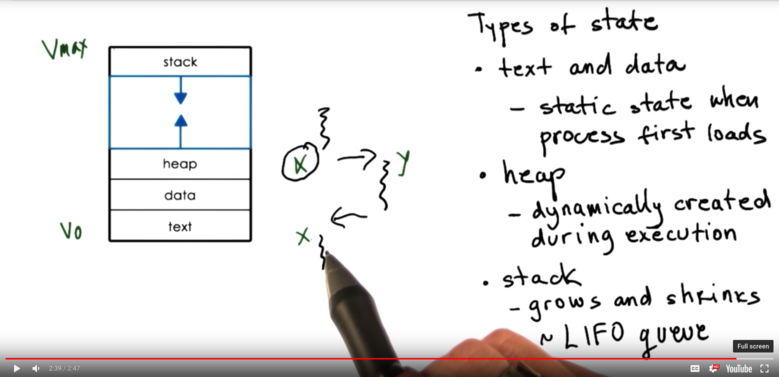

A process encapsulates all of the state of a running application. This includes the code, the data, the heap, and the stack. Every element of the process state has to be uniquely identified by its address. An operating system abstraction used to encapsulate all of the process state is an address space.

The address space is defined by a range of addresses V_0 to V_max. Different types of process state will appear in different regions of the address space.

Different types of process state in an address space:

The code

The data available when process is first initialized (static state)

Heap: Dynamically created state (what we create)

Seems contiguous but there are holes filled with garbage (think of C struct not

memset)

Stack: Dynamically created state that grows and shrinks are the program executes

LIFO

Stack frames added and removed as functions are called and return

Process Address Space

Potential range of addresses in process address space go from V_0 to V_max. These addresses are called virtual addresses. They are virtual because they don't have to correspond to actual locations in the physical memory.

Memory management hardware and components of the operating system maintain a mapping between virtual memory addresses and physical memory addresses. By using this mapping, we can decouple the layout of the data in the virtual address space from the layout of the data in physical memory.

For example, data may live at 0x03c5 in the virtual address space and this may map to 0x0f0f in physical memory.

The operating system creates a mapping between the virtual address and the physical address so that processes can access their data without knowing its physical location. This mapping is called a page table.

Address Space and Memory Management

We may not have enough physical memory to store all a process's state even if we do need it. To deal with this overflow, the operating system decides dynamically which portion of the process's address space will live in physical memory and which portion will be swapped temporarily to disk.

Operating system must maintain a mapping from the virtual addresses to the physical addresses, and must also check the validity of memory accesses, to make sure that, say, process A isn't trying to write to memory mapped to by process B.

Process Execution State

For an operating system to manage processes, it must have some idea about what a process is "doing". If the operating system stops a process, for example, it must know exactly what it was doing when it was stopped, so it can resume its execution with the exact same state.

At any given time the CPU must know where within a program's code a process currently is. The CPU's knowledge of the current executing line within a program is the program counter.

The program counter is maintained on a CPU's register while the program is executing. Other data related to a current process's state is also stored on CPU registers.

Another piece of state the defines what a process is doing is the process's stack. The top of the stack is defined by the stack pointer.

To maintain all of this useful information for every single process, the operating system maintains a process control block or PCB.

Process Control Block

A process control block is a data structure that the operating system maintains for every process that it manages.

Process control block contains:

process state

process number

program counter

CPU registers

memory limits

CPU scheduling info

and more!

The PCB is created when the process is initially created, and is also initialized at that time. For example, the program counter will be set to point at the very first instruction.

Certain fields of the PCB may changed when process state changes. For example, virtual/physical memory mappings may be updated when the process requests more memory.

Some fields can change often, like the program counter. We don't want to waste time on every instruction changing the counter. The CPU maintains a register just for the program counter which it can update (efficiently?) on every new instruction.

It is the job of the operating system to collect all of the data about a process - stored within CPU registers - and save it to the PCB when the process is no longer running.

How is PCB Used?

PCBs are stored in memory on behalf of a process by the operating system until it comes time for the process to start/resume execution. At that point, the process's PCB is loaded from memory into CPU registers, at which point instruction execution can begin.

If a process is interrupted by the operating system - perhaps to give another process some CPU time - the operating system must pull the PCB out of CPU registers and save it back into memory.

Each time the operating system switches between processes, we call this a context switch.

Context Switch

PCB blocks corresponding to each process will reside in memory until the operating system loads that data into the CPU registers, at which point the process can begin executing instructions.

A context switch is a mechanism used by the operating system to switch from the context of one process to the context of another process.

This operation is EXPENSIVE.

We incur direct costs, which are the number of CPU cycles required to load and store a new PCB to and from memory.

We also incur indirect costs. When a process is running on the CPU a lot of its data is stored in the processor cache. Accessing data from cache is very fast (on the order of cycles) relative to accessing data from memory (on the order of hundreds of cycles). When we data we need is present in the cache, we say that the cache is hot. When a process gets swapped out, all of it's data is cleared from cache. The next time it is swapped in, the cache is cold. That is, the data is not in the cache and the CPU has to spend many more cycles fetching data from memory.

Basically, we want to limit how often we context switch!

Process Life Cycle: States

When a process is created, it is in the new state. This is when the OS performs admission control, and allocates/initializes the PCB for this process. At this point, the process moves to the ready state, where it is ready to start executing, but isn't currently executing. When the scheduler schedules the process and it moves on to the CPU it is in the running state. The process can be interrupted and a context switch can be performed. This moves the process back to the ready state. Alternatively, the running process may need to perform some I/O operation or wait on an event, at which point the process enters a waiting state. The process can then move back to ready when the I/O operation completes or the event occurs. Finally, a process can exit, with or without error, and at this point the process is terminated.

Process Life Cycle: Creation

In operation systems, a process can create one or more child processes. The creating process is the parent and the created process is the child. All of the processes that are currently loaded will exist in a tree-like hierarchy.

Once the operating system is done booting, it will create some root processes. The processes have privileged access.

Most operating systems support two mechanisms for process creation:

fork

exec

With fork, the operating system will create a new PCB for the child, and then will copy the exact same values from the parent PCB into the child PCB. The result is that both processes will continue executing with the exact same state at the instruction immediately following the fork (they have the same program counter).

With exec, the operating system will take a PCB (created via fork), but will not leave the values to match those of the parents. Instead operating system loads a new program, and the child's PCB will now point to values that describe this new program. The program counter of the child will now point to the first instruction of the new program.

For "creating" a new program, you have to call fork to get a new process, and then call exec to load that program's information into the child's PCB.

Role of the CPU scheduler

For the CPU to start executing a process, the process must first be ready. At any given time, there may be many processes that are in the state, so the questions becomes: how does the operating system decide which process to run next on the CPU?

This is determined by an operating system component known as the CPU scheduler. The CPU scheduler manages how processes use the CPU resources. It determines which process will use the CPU next, and how long that process has to run.

The operating system must be able preempt; that is, interrupt the current process and save its context. The operating system must then run the scheduler to schedule, or select, the next process. Once the process is chosen, the operating system must dispatch the process and switch into its context.

Since CPU resources are precious, the operating system needs to make sure that it spends the bulk of its time running processes, NOT making scheduling decisions.

Length of Process

One issue to consider is how often we run the scheduler. Put another way, the operating system has to make smart decisions about how long a process can run.

We can calculate a measure of CPU efficiency by looking at the amount of time spent executing a process divided by the total amount of computation time.

For example, if the number of blocks of time spent scheduling equals the number of blocks spent executing, and the length of an execution block is the same as the length of a scheduling block, then the CPU efficiency is only 50%!

On the other hand, if the same number of blocks are spent scheduling as are spent executing, but the process runs for 10 times the length of the scheduling block, the efficiency increases to over 90%!

The amount of time that has been allocated to a process that is scheduled to run is known as a timeslice.

When designing a scheduler, we have to make important design decisions:

What are appropriate timeslice values?

What criteria is used to decide which process is the next to run?

What about I/O

When a process makes an I/O request, the operating system will deliver that request, and move the process to the I/O queue for that particular I/O device. The process will remain in the queue until the request is responded to, after which the process will move back to a ready state (or might immediately be scheduled on the CPU).

Processes can end up on the ready queue in a few ways.

Inter Process Communication

Can processes interact? YES! It is common today that an application consists of multiple processes, so it is important that one process can talk to another.

Example: Web application! Web server running in one process, database running in another.

These mechanisms that allow processes to talk to one another are known as inter process mechanisms (IPCs).

These mechanisms help to transfer data/information between address spaces while maintaining protection and isolation. There are many different types of inter process communication, so these mechanisms needs to be flexible and performant.

Message Passing IPC

Operating system establishes a communication channel - like a shared buffer, for instance - and the processes use that to communicate. One process can write/send through the channel, while the other can read/recv from the channel.

Benefits of this approach is that the operating system will manage this channel, and already has the system calls in place for write/send and read/recv.

Downsides are overhead. Every single piece of information to be transmitted needs to be copied from address space of sending process into memory allocated to the kernel, and then finally into the address space of the receiving process.

Shared Memory IPC

The operating system establishes a shared memory channel, and then maps it into the address space of both processes. The processes are then allowed to directly read/write to this memory the same way they can read/write from any memory allocated them in their address space.

The operating system is completely out of the picture in this case, which is the main benefit! No overhead to incur.

The disadvantage to this approach is that because the OS is out of the way, a lot of the APIs that were taken for granted in message passing IPC have to be reimplemented.

Last updated