Thread Design Considerations

Kernel Vs. User Level Threads

Threads can be supported at the user level, the kernel level, or both.

Supporting threads at the kernel level means that the operating system itself is multithreaded. To do this the kernel must maintain some data structure to represent threads, and must also maintain all of the scheduling and syncing mechanisms to make multithreading correct and efficient.

Supporting threads at the user level means there is a user level library linked with the application that provides all of the management and support for threads. It will support the data structure as well as the scheduling mechanisms. Different processes may use entirely different user level thread libraries.

User level threads can be mapped onto kernel level threads via a 1:1, many:1 and many:many patterns.

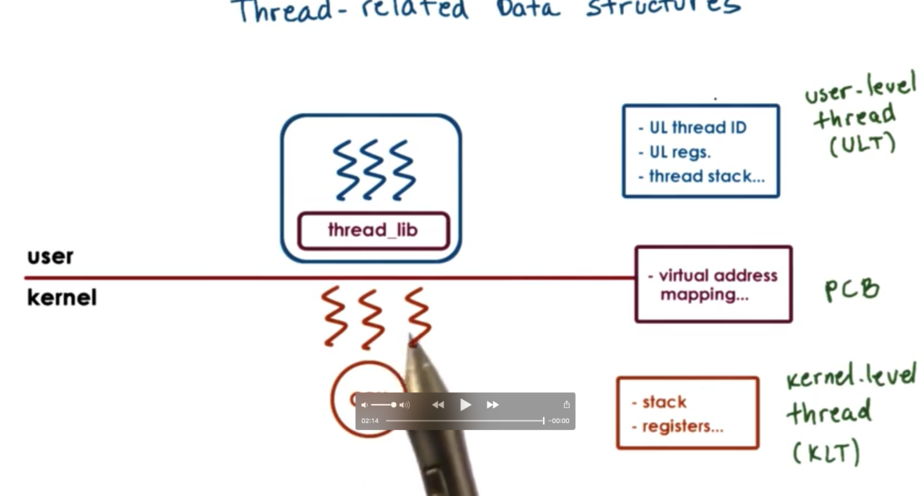

Thread Related Data Structures: Single CPU

A process is described by its process control block, which contains:

virtual address mapping

stack

registers

If the process links in a user level threading library, that library will need some way to represent threads, so that it can track thread resource use and make decisions about thread scheduling a synchronization.

The library will maintain some user level thread data structure containing:

thread ids

thread registers

thread stacks

If we want there to be multiple kernel level threads associated with this process, we don't want to have to replicate the entire process control block in each kernel level thread we have access to.

The solution is to split the process control block into smaller structures. Namely, the stack and registers are broken out (since these will be different for different kernel level threads) and only these pieces of information are stored in the kernel level thread data structure.

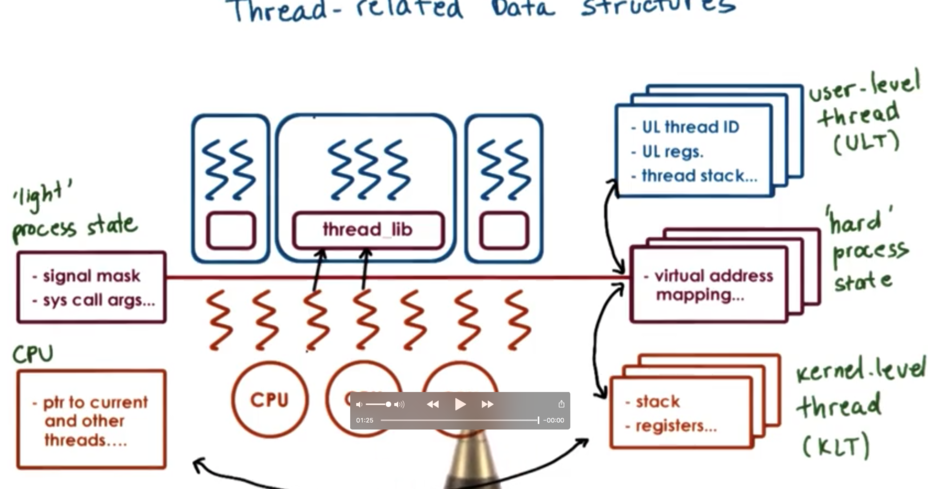

Thread Data Structures: At Scale

If we have multiple processes, we will need copies of the user level thread structures, process control blocks, and kernel level thread structures to represent every aspect of every process.

We need to start maintaining relationships among these data structures. The user level library keeps track of all of the user level threads for a given process, so there is a relationship between the user level threads and the process control block that represents that process. For each process, we need to keep track of the kernel level threads that execute on behalf of the process, and for each kernel level thread, we need to keep track of the processes on whose behalf we execute.

If the system has multiple CPUs, we need to have a data structure to represent those CPUs, and we need to maintain a relationship between the kernel level threads and the CPUs they execute on.

When the kernel itself is multithreaded, there can be multiple threads supporting a single process. When the kernel needs to context switch among kernel level threads, it can easily see if the entire PCB needs to be swapped out, as the kernel level threads point to the process on behalf of whom they are executing.

Hard and Light Process State

When the operating system context switches between two kernel level threads that belong to the process, there is information relevant to both threads in the process control block, and also information that is only relevant to each thread.

Information relevant to all threads includes the virtual address mapping, while information relevant to each thread specifically can include things like signals or system call arguments. When we context switch among the two kernel level threads, we want to preserve some portion of the PCB and swap out the rest.

We can split up the information in the process control block into hard process state which is relevant for all user level threads in a given process and light process state that is only relevant for a subset of user level threads associated with a particular kernel level thread.

Rationale For Data Structures

Single control block:

large continuous data structure

private for each entity (even though some information can be shared)

saved and restored in entirety on each context switch

updates may be challenging

Multiple data structures:

smaller data structures

easier to share

save and restore only what needs to change on context switch

user-level library only needs to update a portion of the state for customized behavior

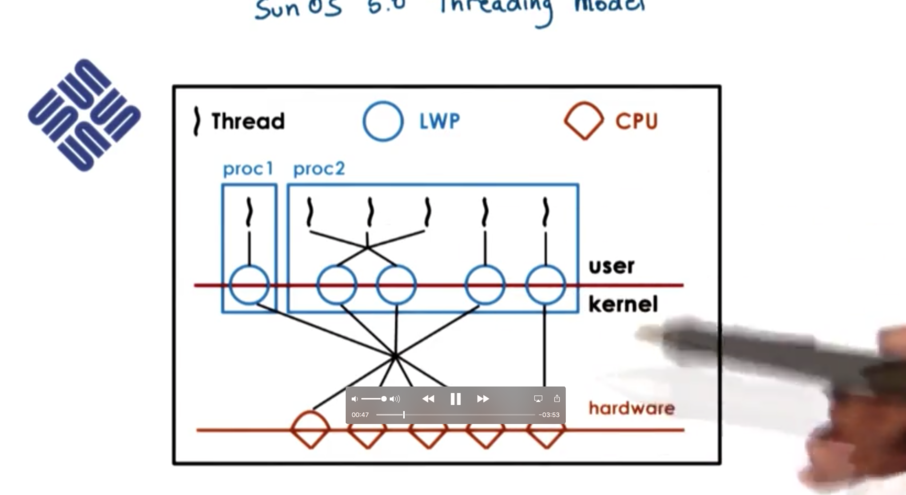

User Level Structures in Solaris 2.0

SunOS paper

The OS is intended for multiple CPU platforms and the kernel itself is multithreaded. At the user level, the processes can single or multithreaded, and both many:many and one:one ULT:KLT mappings are supported.

Each kernel level thread that is executing on behalf of a user level thread has a lightweight process (LWP) data structure associated with it. From the user level library perspective, these LWPs represent the virtual CPUs onto which the user level threads are scheduled. At the kernel level, there will be a kernel level scheduler responsible for scheduling the kernel level threads onto the CPU.

Lightweight Threads paper

When a thread is created, the library returns a thread id. This id is not a direct pointer to the thread data structure but is rather an index into an array of thread pointers.

The nice thing about this is that if there is a problem with the thread, the value at the index can change to say -1 instead of the pointer just pointing to some corrupt memory.

The thread data structure contains different fields for:

execution context

registers

signal mask

priority

stack pointer

thread local storage

stack

The amount of memory needed for a thread data structure is often almost entirely known upfront. This allows for compact representation of threads in memory: basically, one right after the other in a contiguous section of memory.

However, the user library does not control stack growth. With this compact memory representation, there may be an issue if one thread starts to overrun its boundary and overwrite the data for the next thread. If this happens, the problem is that the error won't be detected until the overwritten thread starts to run, even though the cause of the problem is the overwriting thread.

The solution is to separate information about each thread by a red zone. The red zone is a portion of the address space that is not allocated. If a thread tries to write to a red zone, the operating system causes a fault. Now it is much easier to reason about what happened as the error is associated with the problematic thread.

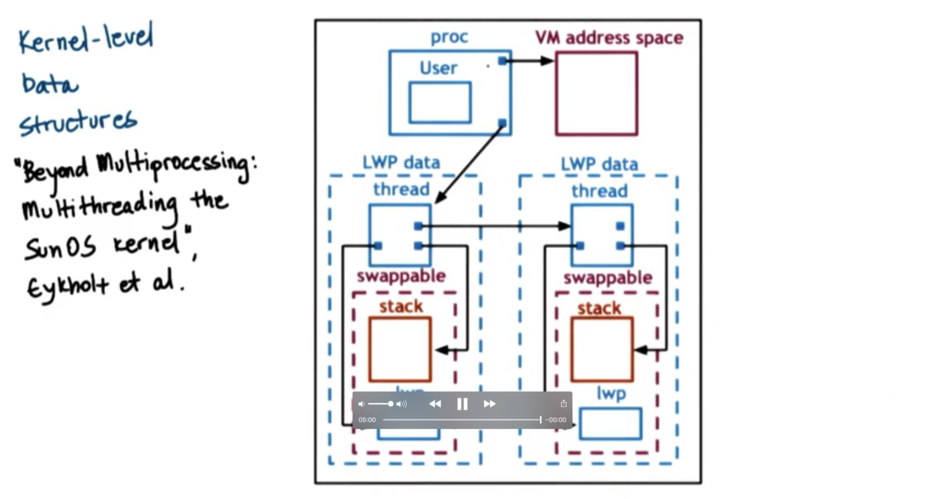

Kernel Level Structures in Solaris 2.0

For each process, the kernel maintains a bunch of information, such as:

list of kernel level threads

virtual address space

user credentials

signal handlers

The kernel also maintains a light-weight process (LWP), which contains data that is relevant for some subset of the user threads in a given process. The data contained in an LWP includes:

user level registers

system call arguments

resource usage info

signal masks

The data contained in the LWP is similar to the data contained in the ULT, but the LWP is visible to the kernel. When the kernel needs to make scheduling decisions, they can look at the LWP to help make decisions.

The kernel level thread contains:

kernel-level registers

stack pointer

scheduling info

pointers to associated LWPs, and CPU structures

The kernel level thread has information about an execution context that is always needed. There are operating system services (for example, scheduler) that need to access information about a thread even when the thread is not active. As a result, the information in the kernel level thread is not swappable. The LWP data does not have to be present when a process is not running, so its data can be swapped out.

The CPU data structure contains:

current thread

list of kernel level threads

dispatching & interrupt handling information

Given a CPU data structure it is easy to traverse and access all the other linked data structures. In SPARC machines (what Solaris runs on), there is a dedicated register that holds the thread that is currently executing. This makes it even easier to identify and understand the current thread.

A process data structure has information about the user and points to the virtual address mapping data structure. It also points to a list of kernel level threads. Each kernel level thread structure points to the lightweight process and the stack, which is swappable.

Basic Thread Management Interaction

Consider a process with four user threads. However, the process is such that at any given point in time the actual level of concurrency is two. It always happens that two of its threads are blocking on, say, IO and the other two threads are executing.

If the operating system has a limit on the number of kernel threads that it can support, the application might have to request a fixed number of threads to support it. The application might select two kernel level threads, given its concurrency.

When the process starts, maybe the operating system only allocates one kernel level thread to it. The application may specify (through a set_concurrency system call) that it would like two threads, and another thread will be allocated.

Consider the scenario where the two user level threads that are scheduled on the kernel level threads happen to be the two that block. The kernel level threads block as well. This means that the whole process is blocked, even though there are user level threads that can make progress. The user threads have no way to know that the kernel threads are about to block, and has no way to decide before this event occurs.

What would be helpful is if the kernel was able to signal to the user level library before blocking, at which point the user level library could potentially request more kernel level threads. The kernel could allocate another thread to the process temporarily to help complete work, and deallocate the thread it becomes idle.

Generally, the problem is that the user level library and the kernel have no insight into one another. To solve this problem, the kernel exposes system calls and special signals to allow the kernel and the ULT library to interact and coordinate.

Thread Management Visibility and Design

The kernel sees:

Kernel level threads

CPUs

Kernel level scheduler

The user level library sees:

User level threads

Available kernel level threads

The user level library can request that one of its threads be bound to a kernel level thread. This means that this user level thread will always execute on top of a specific kernel level thread. This may be useful if in turn the kernel level thread is pinned to a particular CPU.

If a user level thread acquires a lock while running on top of a kernel level thread and that kernel level thread gets preempted, the user level library scheduler will cycle through the remaining user level threads and try to schedule them. If they need the lock, none will be able to execute and time will be wasted until the thread holding the lock is scheduled again.

The user level library will make scheduling changes that the kernel is not aware of which will change the ULT/KLT mapping in the many to many case. Also, the kernel is unaware of the data structures used by the user level, such as mutexes and wait queues.

We should look at 1:1 ULT:KLT models.

The process jumps to the user level library scheduler when:

ULTs explicitly yield

Timer set by the by UL library expires

ULTs call library functions like lock/unlock

blocked threads become runnable

The library scheduler may also gain execution in response to certain signals from timers and/or the kernel.

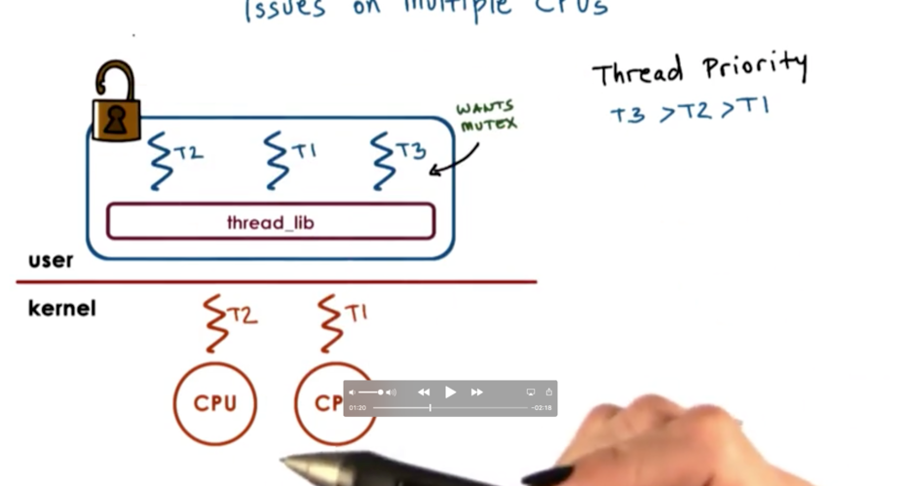

Issue On Multiple CPUs

In a multi CPU system, the kernel level threads that support a process may be running concurrently on multiple CPUs. We may have a situation where the user level library that is operating in the context of one thread on one CPU needs to somehow impact what is running on another CPU.

Scenario

Currently, T2 is holding the mutex and is executing on one CPU. T3 wants the mutex and is currently blocking. T1 is running on the other CPU.

At some point, T2 releases the mutex, and T3 becomes runnable. T1 needs to be preempted, but we make this realization from the user level thread library as T2 is unlocking the mutex. We need to preempt a thread on a different CPU!

We cannot directly modify the registers of one CPU when executing as another CPU. We need to send a signal from the context of one thread on one CPU to the context of the other thread on the other CPU, to tell the other CPU to execute the library code locally, so that the proper scheduling decisions can be made.

Once the signal occurs, the library code can block T1 and schedule T3, keeping with the thread priorities within the application.

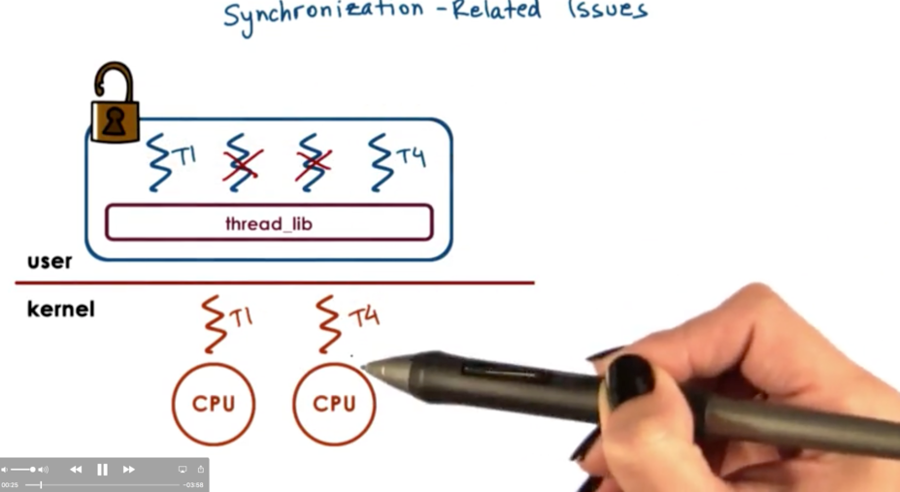

Synchronization Related Issues

Scenario

T1 holds the mutex and is executing on one CPU. T2 and T3 are blocked. T4 is executing on another CPU and wishes to lock the mutex.

The normal behavior would be to place T4 on the queue associated with the mutex. However, on a multiprocessor system where things can happen in parallel, it may be the case that is the time T4 is placed on the queue, T1 has released the mutex.

If the critical section is very short, the more efficient case for T4 is not to block, but just to spin (trying to acquire the mutex in a loop). If the critical section is long, it makes more sense to block (that is, be placed on a queue and retrieved at some later point in time). This is because it takes CPU cycles to spin, and we don't want to burn through cycles for a long time.

Mutexes which sometimes block and sometimes spin are called adaptive mutexes. These only make sense on multiprocessor systems, since we only want to spin if the owner of the mutex is currently executing in parallel to us.

We need to store some information about the owner of a given mutex at a given time, so we can determine if the owner is currently running on a CPU, which means we should potentially spin. Also, we need to keep some information about the length of the critical section, which will give us further insight into whether we should spin or block.

Once a thread is no longer needed, the memory associated with it should be freed. However, thread creation takes time, so it makes sense to reuse the data structures instead of freeing and creating new ones.

When a thread exits, the data structures are not immediately freed. Instead, the thread is marked as being on death row. Periodically, a special reaper thread will perform garbage collection on these thread data structures. If a request for a thread comes in before a thread on death row is reaped, the thread structure can be reused, which results in some performance gains.

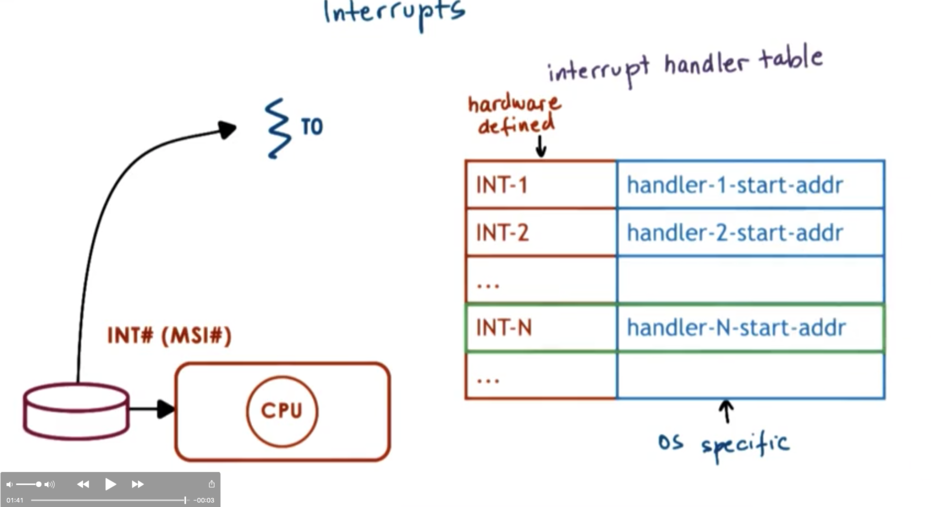

Interrupts and Signals Intro

Interrupts

Interrupts are events that are generated externally by components other than the CPU to which the interrupt is delivered. Interrupts are notifications that some external event has occurred.

Components that may deliver interrupts can include:

I/O devices

Timers

Other CPUs

Which particular interrupts can occur on a given physical platform depends on the configuration of that platform, the types of devices the platform comes with, and the hardware architecture of the platform itself.

Interrupts appear asynchronously. That is, they do not appear in response to any specific action that is taking place on the CPU.

Signals

Signals are events that are triggered by the CPU and the software running on it.

Which signals can occur on a given platform depends very much on the given operating system. Two identical platforms will have the same interrupts but will have different signals if they are running different operating systems.

Signals can appear both synchronous and asynchronously. Signals can occur in direct response to an action taken by a CPU, or they can manifest similar to interrupts.

Signal/Interrupt Similarities

Both signals and interrupts have a unique identifier whose values depend on the hardware or operating system.

Both interrupts and signals can be masked. An interrupt can be masked on a per-CPU basis and a signal can be masked on a per-process basis. A mask is used to disable or delay the notification of an incoming interrupt or signal.

If the mask indicates that the corresponding interrupt or signal is enabled, the incoming notification will trigger the corresponding handler. Interrupt handlers are specified for the entire system, by the operating system. Signal handlers are set on a per-process basis, by the process itself.

Interrupt Handling

When a device wants to send a notification to the CPU, it sends an interrupt by sending a signal through the interconnect that connects the device to the CPU.

Most modern devices use a special message, MSI that can be carried on the same interconnect that connects the device to the CPU complex. Based on the pins on where the interrupt is received or the message itself, the interrupt can be uniquely identified.

The interrupt interrupts the execution of the thread that was executing on top of the CPU, so now what? The CPU looks up the interrupt number in a table and executes the handler routine that the interrupt maps to. The interrupt number maps to the starting address of the handling routine, and the program counter can be set to point to that address to start handling the interrupt.

All of this happens within the context of the thread that is interrupted.

Which interrupts can occur depends on the hardware of the platform and how the interrupts are handled depends on the operating system running on the platform.

Signal Handling

Signals are different from interrupts in that signals originate from the CPU. For example, if a process tries to access memory that has not been allocated, the operating system will generate a signal called SIGSEGV.

For each process, the OS maintains a mapping where the keys correspond to the signal number (SIGSEGV is signal 11, for example), and the values point to the starting address of handling routines. When a signal is generated, the program counter is adjusted to point to the handling routine for that signal for that process.

The process may specify how a signal can be handled, or the operating system default may be used. Some default signal responses include:

Terminate

Ignore

Terminate and Core Dump

Stop

Continue (from stopped)

For most signals, processes can install its custom handling routine, usually through a system call like signal or sigaction although there are some signals which cannot be caught.

Some synchronous signals include:

SIGSEGV

SIGFPE (divide by zero)

SIGKILL (from one process to another)

Some asynchronous signals include:

SIGKILL (as the receiver)

SIGALARM (timeout from timer expiration)

Why Disable Interrupts or Signals?

Interrupts and signals are handled in the context of the thread being interrupted/signaled. This means that they are handled on the thread's stack, which can cause certain issues.

When a thread handles a signal, the program counter of the thread will point to the first address of the handler. The stack pointer will remain the same, meaning that whatever the thread was doing before being interrupted with still be on the stack.

If the handling code needs to access some shared state that can be used by other threads in the system, we will have to use mutexes. If the thread which is being interrupted had already locked the mutex before being interrupted, we are in a deadlock. The thread can't unlock its mutex until the handler returns, but the handler can't return until it locks the mutex.

To prevent this situation, we can enforce that the handling code stays simple and make sure it doesn't do things like try to acquire mutexes. This of course it too restrictive.

A better solution is to use signal/interrupt masks. These masks allow us to dynamically make decisions as to whether or not signals/interrupts can interrupt the execution of a particular thread.

The mask is a sequence of bits where each bit corresponds to an interrupt or signal and the value - 0 or 1 - signifies whether or not this particular interrupt or signal is disabled or enabled.

When an event occurs, first the mask is checked to determine whether a given interrupt/signal is enabled. If the event is enabled, we proceed with the actual handling code. If the event is disabled, the interrupt/signal is made pending and will be handled at a later time when the mask changes.

To solve the deadlock situation, described above, we must disable the interrupt/signal before acquiring the mutex, and re-enable the interrupt/signal after releasing the mutex. This will ensure that we are never in the handler code when the mutex is locked.

Once the signal is re-enabled, the pending signal is handled by the handler.

While an interrupt or signal is pending, other interrupts or signals may also become pending. Typically the handling routine will only be executed once, so if we want to ensure a signal handling routine is executed more than once, it is not sufficient to just generate the signal more than once.

More on Signal Masks

Interrupt masks are maintained on a per CPU basis. This means that if a mask disables an interrupt, the hardware interrupt routing mechanism will not deliver the interrupt to the CPU.

Signal masks are maintained on a per execution context (ULT on top of KLT). If a mask disables a signal, the kernel will see this and will not interrupt the corresponding execution context.

Interrupts on Multicore Systems

On a multi CPU system, the interrupt routing logic will direct the interrupt to any CPU that at that moment in time has that interrupt enabled. One strategy is to enable interrupts on just one CPU, which will allow avoiding any of the overheads or perturbations related to interrupt handling on any of the other cores. The net effect will be improved performance.

Types of Signals

There are two types of signals.

One-shot signals refer to signals that will only interrupt once. This means that from the perspective of the user level thread, n signals will look exactly like one signal. One-shot signals must also be explicitly re-enabled every time.

Real-Time Signals refer to signals that will interrupt as many times are they are raised. If n signals occur, the handler will be called n times.

Interrupts as Threads

To avoid the deadlock situation we covered before with regards to handler code trying to lock a mutex that the thread had already locked, perhaps it makes sense to have handler code exist in its own thread.

This way, when the thread tries to acquire the mutex, it will block just like any other thread, but will not deadlock. Eventually, the thread holding the mutex will release it, and the handling thread may acquire it.

Dynamic thread creation is expensive! Need to only create a new thread if we need it. If the handler doesn't block, execute on the interrupted thread's stack. Don't make a new thread!

To eliminate the cost of dynamic thread creation, the kernel pre-creates and -initializes thread structures for interrupt routines. This can help reduce the time it takes for an interrupt to be handled.

Interrupts: Top Vs. Bottom Half

When an interrupt is handled in a different thread, we no longer have to disable handling in the thread that may be interrupted. Since the deadlock situation can no longer occur, we don't need to add any special logic to our main thread.

There are two components of signal handling. The top half of signal handling occurs in the context of the interrupted thread (before the handler thread is created). This half must be fast, non-blocking, and include a minimal amount of processing. Once we have created our thread, this bottom half can contain arbitrary complexity, as we have now stepped out of the context of our main program into a separate thread.

Performance of Threads as Interrupts

The overhead of performing the necessary checks and potentially creating a new thread in the case of an interrupt adds about 40 SPARC instructions to each interrupt handling operation.

As a result, it is no longer necessary to disable a signal before locking a mutex and re-enable the signal after releasing the mutex, which saves about 12 instructions per mutex.

Since mutex lock/unlocks occur much more frequently than interrupts, the net instruction count is decreased when using the interrupt as threads strategy.

In general, it is a solid strategy to optimize for the common case. We could have scenarios in which interrupts occur more than mutex lock/unlocks, but we have assumed this is rarely the case, and have optimized for the reverse.

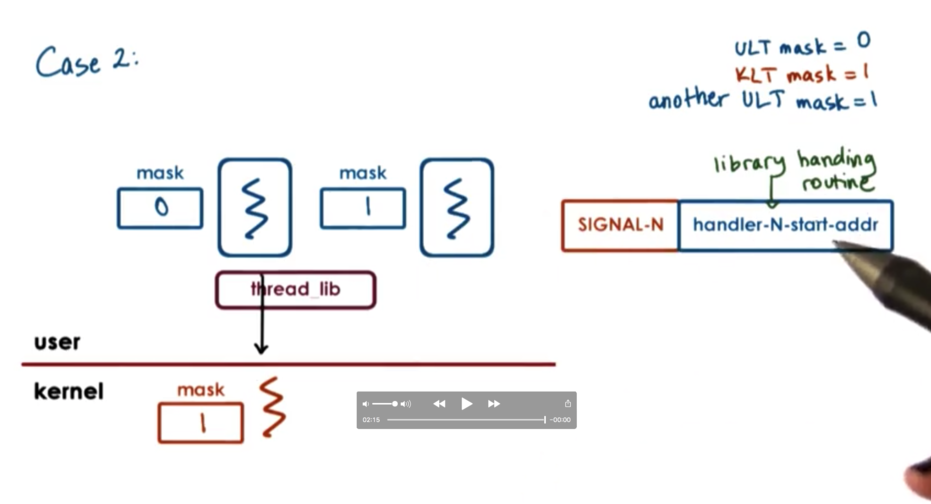

Threads and Signal Handling

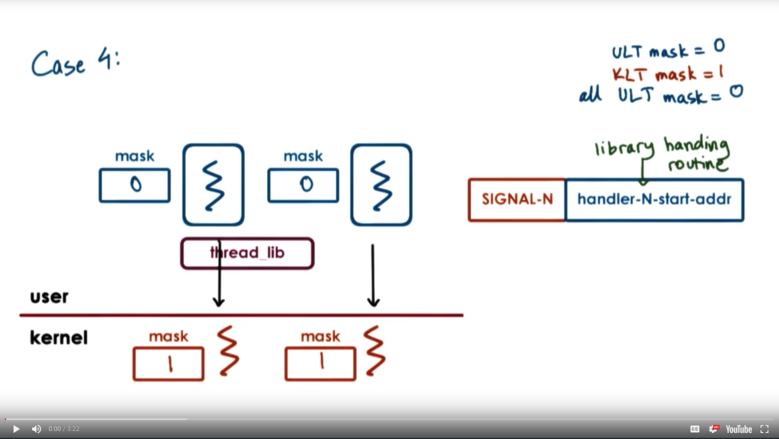

There is a signal mask associated with each user level thread which is associated with the user level process and is visible to the user level library. There is also a signal mask that is associated with the kernel level thread and that kernel level mask is only visible to the kernel.

When a user level thread wants to disable a signal, it clears the appropriate bit in the signal mask, which occurs at user level. The kernel level mask is not updated.

When a signal occurs, the kernel needs to know what to do with the signal. The kernel mask may have that signal bit set to one, so from the kernel's point of view, the signal is still enabled.

If we don't want to have to make a system call, crossing from user level into kernel level each time a user level threads updates the signal mask, we need to come up with some kind of policy.

If both the kernel level thread and the user level thread have the bit enabled, the kernel will send the signal up to the user level thread and we have no problem.

Let's look at a more complicated scenario, in which the kernel level thread has a particular signal bit enabled, and the currently executing user level thread does not. However, there is a runnable user level thread that does have the bit enabled.

What we would like to do is to be able to stop the thread that cannot handle the signal, and start the thread that can.

We can achieve this by having the user level threading library (which has visibility in all threads for a process) being the entity that installs the signal handler. This way, when the signal occurs, the library can invoke the scheduler to swap in a thread that can handle the signal. Once this thread is executing, the signal is passed to its handler.

Let's look at a different scenario, in which user level threads are executing concurrently atop two kernel level threads. Both kernel level threads have the signal bit enabled, while only one of the user level threads does.

In the case where a signal is generated by a kernel level thread that is executing on behalf of a user level thread which does not have the bit enabled, the threading library will know that it cannot pass the signal to this particular user thread.

What it can do, however, is send a directed signal down to the kernel level thread associated with the user level thread that has the bit enabled. This will cause that kernel level thread to raise the same signal, which will be handled again by the user level library and dispatched to the user level thread that has the bit enabled.

Let's consider the final case in which every single user thread has the particular signal disabled. The kernel level masks are still 1, so the kernel still thinks that the process as a whole can handle the signal.

When the signal occurs, the kernel interrupts the execution of whichever thread is currently executing atop it. The library handling routine kicks in and sees that no threads that it manages can handle this particular signal.

At this point, the thread library will make a system call requesting that the kernel level thread change its signal mask for this particular signal, disabling it.

If we have multiple kernel level threads associated with our process, we cannot change all of their signal masks at once. We have to run through this process one by one as signals come in.

At some point in time, a user level thread may decide to re-enable a particular signal. At this point, the user level library must again make a system call, and tell the kernel level thread to update its signal mask for this particular signal, enabling it.

Here we optimize for the common case again. Signals themselves occur much less frequently than does the need to update the signal mask. Updates of the signal mask are cheap. They occur at the user level and avoid system calls. Signal handling becomes more expensive - as system calls may be needed to correct discrepancies - but they occur less frequently so the added cost is acceptable.

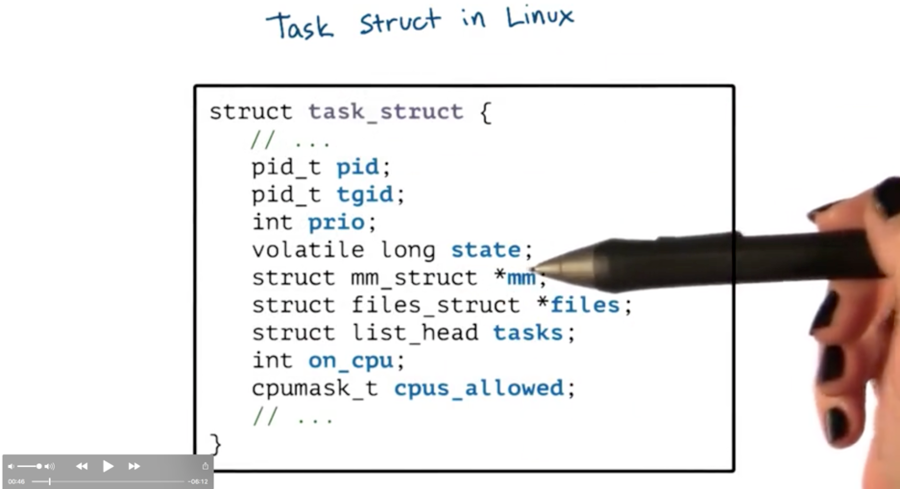

Tasks in Linux

The main abstraction that Linux uses to represent an execution context is called a task. A task is essentially the execution context of a kernel level thread. A single-threaded process will have one task, and a multithreaded process will have many tasks.

Key elements in task structure, encapsulated by struct task_struct

A task is identified by its pid_t pid. If we have a single-threaded process the id of the task and the id of the process will be the same. If we have a multithreaded process, each task will have a different pid and the process as a whole will be identified by the pid of the first task that was created. This information is also captured in the pid_t tgid or task group id, field.

The task structure maintains a list of all of the tasks for a process, whose head is identified by struct list_head tasks.

Linux never had one continuous process control block. Instead, the process state was always maintained through a collection of data structures that pointed to each other. We can see some of the references in the task in struct mm_struct *mm and struct files_struct *files.

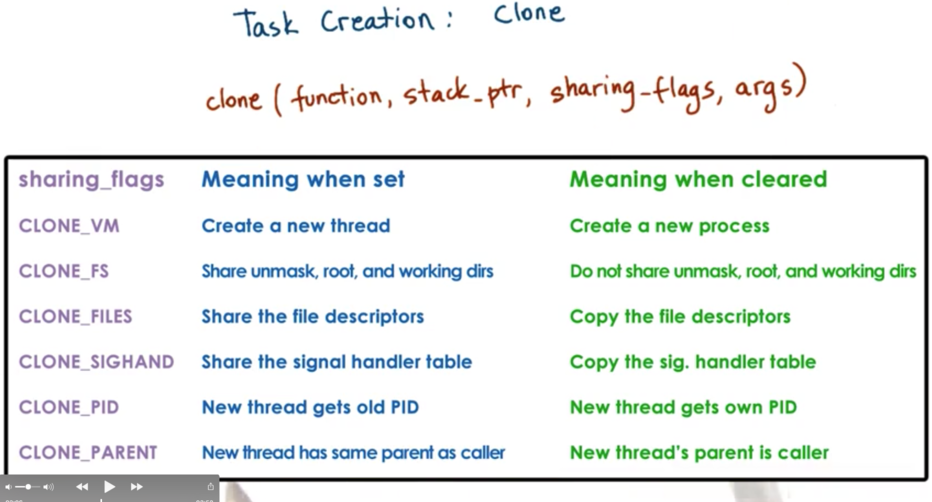

To create a new task, Linux supports an operation called clone. It takes a function pointer and an argument (similar to pthread_create) but it also takes an argument sharing_flags which denotes which portion of the state of a task will be shared between the parent and child task.

When all of the bits are set, we are creating a new thread where the state is shared with the parent thread. If all of the bits are not set, we are not sharing anything, which is more akin to creating an entirely new process. In fact, fork in Linux is implemented by clone with all sharing flags cleared.

The native implementation of threads in Linux is the Native POSIX Threads Library (NPTL). This is a 1:1 model, meaning that there is a kernel level task for each user level thread. This implementation replaced an earlier implementation LinuxThreads, which was a many-to-many model.

In NPTL, the kernel sees every user level thread. This is acceptable because kernel trapping has become much cheaper, so user/kernel crossings are much more affordable. Also, modern platforms have more memory - removing the constraints to keep the number of kernel threads as small as possible.

That being said, when we talk about super large scale or high-level processing, with many many user level threads, it may make sense to revisit more custom threading policies to make systems more scalable and less resource-intensive.

Last updated