Software Defined Networking

Network Management Overview

Network management is the process of configuring the network to achieve a variety of tasks, such as

balancing traffic load

achieving security goals

satisfying business relationships

The key aspect to network management is network configuration, and many things can go wrong if the network is configured incorrectly.

Network Configuration Errors

Persistent oscillations can occur when routers can't agree on a route to a destination.

Loops occur when packets get stuck traveling between two or more routers and never make it to the destination.

Partitions occur when the network is split into two or more segments that are not connected.

Black holes describe the scenario whereby a packet reaches a router that does not know how to forward it. In this case, the router will just drop the packet, unable to forward it towards its destination.

Why is Configuration Hard?

Configuration is hard to get right for several reasons.

First, it can be difficult to define what is meant by "correct behavior" when it comes to routing rules.

Second, the interactions between multiple routing protocols can lead to unpredictable results. Furthermore, since each AS is independently configured, the interactions between the policies of different ASes can lead to unintended behavior.

Finally, operators make mistakes. Configuration is difficult and network policies are very complex. Historically, network configurations have been distributed amongst hundreds (or more) of devices across the network, where each device is configured with vendor-specific, low-level configuration.

The main goal of software defined networking is to centralize the network configuration to a logically centralized controller.

In particular SDN provides operators with three things.

First, SDN provides operators with network-wide views of both topology and traffic.

Second, SDN provides the ability to satisfy network-level objectives, such as load balancing and security.

Third, SDN provides the network operator direct control. Rather than requiring network operators to configure each device individually with indirect configuration, SDN allows an operator to write a control program that directly affects the data plane.

This doesn't mean that routers are no longer important!

Routers should still forward traffic since router hardware is specialized to forward traffic at very high rates. In addition, routers should still collect measurements such as a traffic statistics and topology information.

However, there is no inherent reason that a router needs to compute routes. Even though routing has conventionally operated as a distributed computation of forwarding tables, that computation doesn't need to run on the routers.

Rather, the computation could be logically centralized and controlled from a centralized control program.

A simple way to sum up software-defined network is simply to "remove routing from routers" and perform the routing computation at a logically centralized controller.

Software Defined Networking

What is an SDN?

Contemporary networks have two planes of responsibility.

The task of the data plane is to forward packets to the ultimate destination.

In order for the data plane to fulfill its responsibility, the network needs the ability to compute the state held by each of the routers that is used to make correct forwarding decisions.

These pieces of state are the routing tables, and the control plane is responsible for their computation.

In conventional networks, the control and data plane both run on the routers that are distributed across the network.

In an SDN, the control plane runs in a logically centralized controller, and usually controls all of the routers in the network, providing a network-wide view.

This refactoring allows us to move from a network where devices are vertically integrated - which slows innovation - to a network where devices have open interfaces that can be controlled by software, which allows for much rapid innovation.

History of SDN

Previous to 2004, network configuration was distributed, which led to buggy and unpredictable behavior.

Around 2004, the first logical centralized network controller arrived, in the form of the Routing Control Platform (RCP), which was based off of BGP.

In 2005, researchers generalized the notion of the RCP for different planes through 4D.

In 4D, the decision plane computed the forwarding state for devices in the network, the data plane forwarded traffic based on that forwarding state, and the dissemination and discovery planes provided the decision plane the necessary information for computing the forwarding state.

Around 2008, these concepts hit the mainstream through a protocol called Openflow.

Openflow was made practical when merchant silicon vendors opened their APIs so that switch chipsets could be controlled from software.

Suddenly there was an emergence of cheap switches that were built based on open chipsets that could be controlled from software.

Advantages of SDN

Some of the main benefits of SDN are

easier coordination of behavior across network devices

easier evolution of network behavior

easier to reason about network behavior

These benefits are all rooted in the fact that the control plane is separate from the data plane.

Having a separate control plane allows us to apply conventional CS techniques to old networking problems.

While before it was incredibly difficult to reason about or debug network behavior, we can now leverage techniques from programming languages and software engineering to help us better understand network behavior.

Infrastructure

The control plane is typically a software program written in a high-level language, such as python or C.

The data plane is typically programmable hardware that is controlled by the control plane.

The controller affects the forwarding state in the switch using control commands.

Openflow is one standard that defines a set of control commands by which a controller can control the behavior of one or more switches.

Applications

SDN has many applications, including

data centers

backbone networks

enterprise networks

internet exchange points (IXP)

home networks

Control and Data Planes

The control plane contains the logic that controls forwarding behavior. Control plane functions include

routing protocols

configuration for network middle-boxes

A routing protocol might compute shortest paths over the topology, but ultimately the results of such computation must be installed in switches that actually do the forwarding.

The forwarding table entries themselves and the actions associated with forwarding traffic according to the control plane logic is what constitutes the data plane.

Examples of data plane function include forwarding packets at the IP layer and switching at layer 2.

Why separate data and control?

Separating the data and control planes allows for independent evolution and development. This means that software control of the network can evolve independently of network hardware.

In addition, the opportunity to control network behavior from a high-level software program allows the network operator to debug and check network behavior more easily.

Opportunities

In data centers, the separation of data and control provides opportunities for better network management by facilitating VM migration to adapt to fluctuating network demands.

In routing, this separation provides more control over decision logic.

In enterprise networks, SDN provides the ability to write security applications such as those that manage network access control.

In research networks, the separation of data and control allows researchers to virtualize the network so that research networks and experimental protocols can coexist with production networks on the same underlying network hardware.

Examples

Data Centers

Data centers typically consist of many racks of servers, and any particular cluster might have ~20,000 servers. Assuming that each of these servers can run about 200 virtual machines, there are 4M VMs in a cluster.

A significant problem faced by data centers is provisioning/migrating these machines in response to variable traffic load.

SDN solves this problem by programming switch state from a central database.

If two VMs in the datacenter need to communicate, the forwarding state in the switches in the data center ensure that traffic is forwarded correctly.

If we need to provision additional VMs or migrate a VM from one server to another, the state in these switches must be updated, which is much easier to do from a centralized controller/database.

Facilitating this type of VM migration in a data center is one of the early killer apps of SDN.

This type of migration is also made easier by the fact that these servers are addressed with layer 2 addressing, and the entire datacenter looks like a flat layer 2 topology.

This means that a server can be migrated from one portion of the data center to another without requiring the VM to obtain new addresses.

Backbone Security

In backbone networks, filtering attack traffic is a regular network management task.

Suppose that an attacker is sending a lot of traffic towards a victim.

A measurement system might detect the attack and identify the entry point, at which point the controller might install a null route so that no more traffic reaches the victim from the attacker.

Challenges

Two fundamental challenges with SDN are scalability and consistency.

In SDN, a single control element might be responsible for thousands of forwarding elements. It is imperative that control code is performant and scalable.

While the controller is logically centralized, there may be many physical replicas for the sake of redundancy/reliability. As a result, we need to ensure that different controller replicas see the same view of the network so that they make consistent decisions when installing state in the data plane.

A final challenge is security/robustness. In particular, we want to make sure that the network continues to function correctly in the event that a controller replica fails or is compromised.

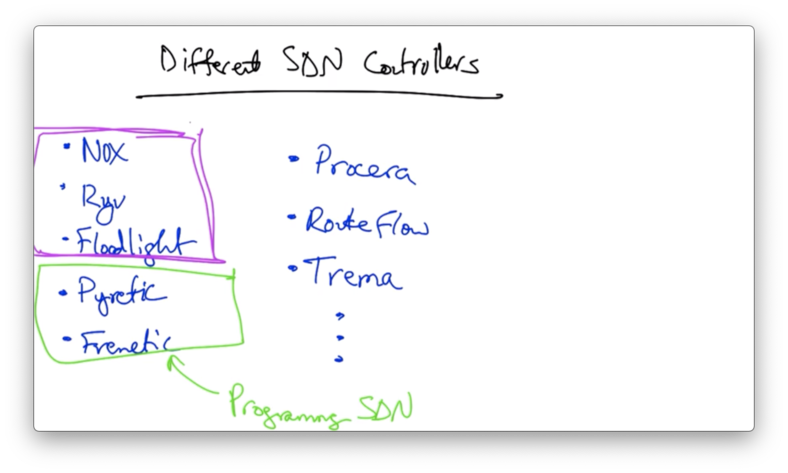

Different SDN Controllers

NOX: Overview

NOX is a first-generation OpenFlow controller. It is open-source, stable and widely used.

There are two flavors of NOX

"classic" NOX (C++/Python, no longer supported)

"new" NOX (C++ only, fast, clean codebase)

Architecture

In a NOX network, there may be a set of switches and various network-attached servers. The controller maintains a network view and may also run several applications that run on top of that network view.

The basic abstraction that NOX supports is the switch control abstraction, whereby OpenFlow is the prevailing protocol.

Control is defined at the granularity of flows, which are defined by a 10-tuple in the original OpenFlow specification.

Depending on whether a particular packet matches a subset of values specified as a flow rule, the controller may make different decisions for packets that belong to different parts of flow space.

Operation

A flow is defined by the header (aforementioned 10-tuple), a counter - which maintains statistics - and actions that should be performed on packets that match this particular flow definition.

Actions might include forwarding the packet, dropping the packet or sending the packet to the controller.

When a switch receives a packet it updates its counters for packets belonging to that flow and applies the corresponding actions for that flow.

Programmatic Interface

The basic programmatic interface for the NOX controller is based on events.

A controller knows how to process different types of a events, such as

switch join/leave

packet received

various statistical events

The controller also keeps track of a network view which includes a view of the underlying network topology, and also speaks a control protocol to the switches in the network via OpenFlow .

Characteristics

NOX is implemented in C++ and supports OpenFlow 1.0. A fork of NOX - known as CPQD - supports OpenFlow 1.1-1.3.

The programming model is event based, and a programmer can write an application by writing event handlers for the NOX controller.

NOX provides good performance, but requires you to understand the semantics of low-level OpenFlow commands.

NOX also requires the programmer to write the control application in C++.

To address the shortcomings that are associated with development in C++, POX was developed.

POX is widely used, maintained and supported. It is also easy to use and easy to read/write the control programs, as POX is implemented in Python.

However, the performance of POX is not as good as the performance of NOX.

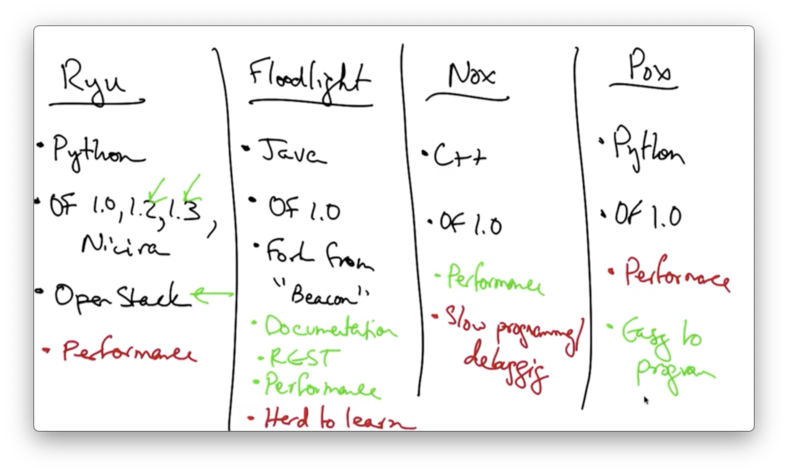

Ryu, Floodlight, Nox and Pox

All of the controllers are still relatively hard to use because they involve interacting directly with OpenFlow flow table modifications, which operate on a very low level.

It's possible to develop programming languages on top of these controllers that make it much easier for a network operator to reason about network behavior.

Customizing Control

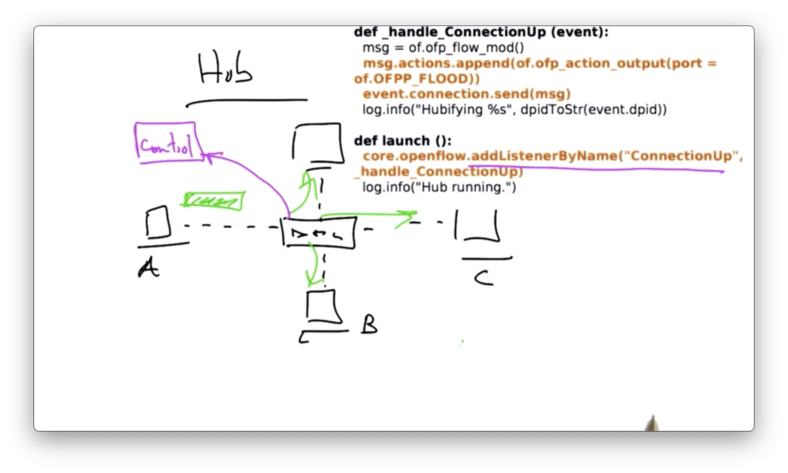

Hubs

A hub maintains no state about which output port a packet should be forwarded to reach a particular destination. Therefore, when a host sends a packet to a hub, the hub simply floods the input packet on every output port.

In POX, this code is fairly simple.

When the controller starts, it adds a listener that listens for a ConnectionUp event which is a connection from a switch. When the switch connects, it sends an OpenFlow flow modification back to the switch that says flood all packets out every output port.

Learning Switch

A learning switch maintains a switch table. This allows for mappings between destination addresses and output ports to be created, which eliminates the need for flooding every packet on every output port.

As before, when the first packet arrives at the switch, it is diverted to the controller.

If the packet is a multicast packet, the controller instructs the switch to flood the packet on all output ports.

If there is no destination for that packet, the controller also instructs the switch to forward the packet on all output ports.

If the source and destination address are the same, the controller instructs the switch to drop the packet.

Otherwise the controller installs the flow table entry corresponding to that destination address and output port.

Installing that flow table entry in the switch prevents future packets for that flow from being redirected to the controller.

Instead, all subsequent packets for that flow can be handled directly by the switch, since it knows which output port to use to forward a packet to that particular destination.

Summary

OpenFlow makes modifying forwarding behavior easy because forwarding decisions are based on matches against the OpenFlow 10-tuple.

Layer 2 switching can be implemented by matching on the destination MAC address and forwarding out a particular output port.

If all of the fields are specified for forwarding out a particular output port, then we have flow switching behavior.

If all of the flow specifications are wildcards except for the source MAC address, then we have a firewall. The controller might maintain a table that maps switches and source MAC addresses to a boolean value, forwarding the packet if the value is true and dropping it otherwise.

Caching

Packets only reach the controller if there is no flow table entry at the switch. If there is an entry at the switch, the switch can just forward the packets directly.

When a controller decides to take an action on a packet, it installs that action in the switch, and the action is then cached until some later expiration time.

Last updated