Cyber Security

Managing Security

The digital components of a business - be they routers, operating systems, or databases - are crucial to successful business operation. A business must implement appropriate security measures to protect these assets against malicious actors attempting to gain unauthorized access.

In addition to mitigating explicit threats, companies often secure our digital assets for legal and compliance reasons. For example, HIPAA mandates a process for sharing digital health data. Therefore, an entity that deals with health data may need to implement specific security measures to meet compliance requirements.

We've spent time talking about the various technical controls - such as firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and anti-virus programs - that organizations can use to secure their computer systems.

Of course, a business must first understand the risks that they face and the threat landscape surrounding their organization and digital assets before implementing any security measure.

Additionally, technical implementations carry associated costs, and businesses are wise to ensure that the cost of securing a system does not exceed the value of the system.

Key Challenges

A business faces different challenges during the process of building and implementing a cybersecurity plan.

For example, a business must identify their assets and the relative value of these assets. Furthermore, a business must understand which assets are at risk, how severe the risk is, and how threat sources are likely to present themselves.

After a business surveys the security landscape of their organization, they then have to implement the security measures. This implementation step requires awareness of the various security solutions and controls present in the market.

Additionally, organizations must perform a cost-benefit analysis before deploying a particular solution. While a business wants to reduce risk, they likely don't want to spend more than the value of the asset they are protecting.

Finally, a business must understand how the employees operate within the organization and the various workflows that a new security implementation can impact. Employees are likely to skirt security measures that drastically hinder their productivity.

Network Use Policy Quiz

Network Use Policy Quiz Solution

Botnet Quiz

Botnet Quiz Solution

Security Planning

So far, we've identified the assets that need protection, determined the parties responsible for understanding the security needs of the organization, examined the technical controls at our disposal, and understood the impact of different implementations on user workflow.

During the process of security planning, a business has to understand that no matter how well they deploy their security, they can never reduce the risk to zero. Therefore, the planning process needs to cover response and recovery as well as prevention and detection.

One component of incident response is accountability. When an incident occurs, the business needs to understand which responsibilities were not fulfilled and take steps to hold the appropriate employees accountable.

Assets and Threats

A business must take inventory of their assets to understand which assets are valuable. These assets include servers, routers, switches, laptops, and mobile devices.

In addition to the physical assets themselves, a business needs to consider the software utilized by these assets; for example, the operating systems running on the servers, laptops and mobile devices; the databases that store large amounts of data, and; the services and applications running on these devices.

The organization must concern themselves with the data stored in the system, whether structured data that lives in databases or unstructured data in files in the filesystem. Some of this data, such as intellectual property, financial records, or customer information, can be sensitive and, therefore, may require additional security measures.

Assets only require security if they are at risk, so a business needs to understand who they are securing their assets from before implementing security controls. These threat actors could be external cybercriminals, passionate hacktivists, or even disgruntled employees.

Security Audit Quiz

Security Audit Quiz Solution

NOTE: answers 1 and 3 are correct.

CISO Quiz

CISO Quiz Solution

Security Planning: Controls

Security planning involves understanding which security controls make the most sense for a given organization's assets and threat posture. Let's take a look at a few of these controls.

Identity and Access Management (IAM) is a popular security control. The "identity" part of IAM serves to identify a user who is requesting any type of resource present in the system. The "access management" component of IAM serves to perform access control on the resource, ensuring that a user has sufficient permission to access the resource they have requested.

Credentialing is another security measure that concerns resource access. When a business provides a user with a credential, the credential serves as a proxy for the user's identity, allowing them to access resources without explicitly identifying themselves each time.

A business may have certain password policies, which dictate how long a password must be and how frequently a password needs to change. Additionally, some organizations may require multi-factor authentication; for example, a user may need to use a password and a smart card to access specific resources.

A business can deploy network and host defenses to protect their resources. For example, firewalls control the traffic that enters and exits a network, and intrusion detection systems and intrusion prevention systems monitor the traffic at the network level and raise alarms when they detect suspicious activity. Anti-virus systems running on local machines help control which external software a user can download and run.

If employees need to access critical systems from external networks, a business may require a VPN solution to tunnel business traffic through these networks securely. Additionally, organizations that permit employees to bring their own devices need to have a plan for securing those devices.

New vulnerabilities are found in software all the time. A business must have a strategy for discovering vulnerabilities and patching them in a timely fashion.

Besides deploying technological controls, a business can also look at employee education. For example, many companies periodically run fake phishing campaigns to show employees what a real phishing attack might resemble. Educational exercises like this can supplement purely technical security solutions.

Security Planning: Security Policy

Security planning requires that a business develops a security policy. A security policy articulates the security objectives and goals of an organization, and specifies the rules the organization needs to implement to achieve those objectives.

A security policy often incorporates legal, compliance, and business rationale for the rules it chooses to implement. Security policies may concern prevention and detection, as well as recovery and response.

An organization might have many security goals, such as

preventing unauthorized data disclosure

ensuring system availability

guarding against data corruption

abiding by compliance requirements

To achieve these goals, an organization must implement certain rules. For example, many companies have web and email policies that restrict the use of these facilities from within the corporate network. A web policy may dictate which sites an employee can visit, while an email policy may restrict a user from corresponding with certain addresses or opening certain attachments.

Georgia Tech Computer and Network Use Policy

Like many organizations, Georgia Tech (GT) has a security policy, the Computer Network Usage and Security Policy. One guiding principle of this policy is to protect valuable IT resources that GT owns, including the data stored on and services used by these resources. Another guiding principle is to prevent any illegal activity from taking place on GT networks and devices.

You can read the entire policy by clicking the link above. We cover a few interesting highlights here.

The policy talks about intellectual property and copyright. As a research institution, GT creates intellectual property that resides on their computers and must decide how to store and share that information. Additionally, GT has to explicitly address copyrighted material since many colleges got in trouble in the past when students would use university networks to download illegal music.

GT is home to individuals from all over the world, and many people work with counterparts in other countries. Since working across national boundaries can raise issues related to customs and border control, the security policy must address these issues.

An organization must define responsibility and accountability when creating a security policy. The security planning process must involve identifying who is responsible for what resources and how they should be held accountable for those resources.

The GT policy defines a distributed model of responsibility. The centralized Office of Information Technology is responsible for the overall university network. Individual devices, such as workstations, are the responsibility of particular units - the College of Computing, for example - or the individual in possession of the devices.

Computer Use Policy Quiz

Computer Use Policy Quiz Solution

Student Privacy Quiz

Student Privacy Quiz Solution

Anthem Breach Quiz

Anthem Breach Quiz Solution

Cyber Risk Assessment

Unless a business disconnects from the rest of the world, they cannot eliminate their risk. Regardless of how well an organization plans or how many controls they implement, the possibility of compromise is greater than zero. Systems have unknown vulnerabilities, and people get phished: something can always go wrong.

A business must perform cost-benefit analyses when planning to implement security controls. An investment in cybersecurity requires money and effort, and the investment decisions must be based on risk and its reduction. A business may want to understand how much risk is reduced, from a financial perspective, as a result of purchasing some security control.

These decisions require businesses to quantify their risk. While various frameworks can help a business reduce relative risk, putting a dollar amount to the overall risk faced by an organization is not an easy task.

Quantifying Cyber Risk

When a business wants to quantify risk, they need to consider two things. First, they need to look at the probability of an adverse security event happening. For a given set of assets, threat landscape, and set of security controls, there is some nonzero probability of system compromise. Second, the business must consider the financial impact of the adverse event. For example, a data breach may cost a company $10 million.

For a probability P and impact I, we can define risk exposure R = PI. For example, given a 50% chance of an adverse security event that is going to cost $10 million, the risk exposure is $5 million.

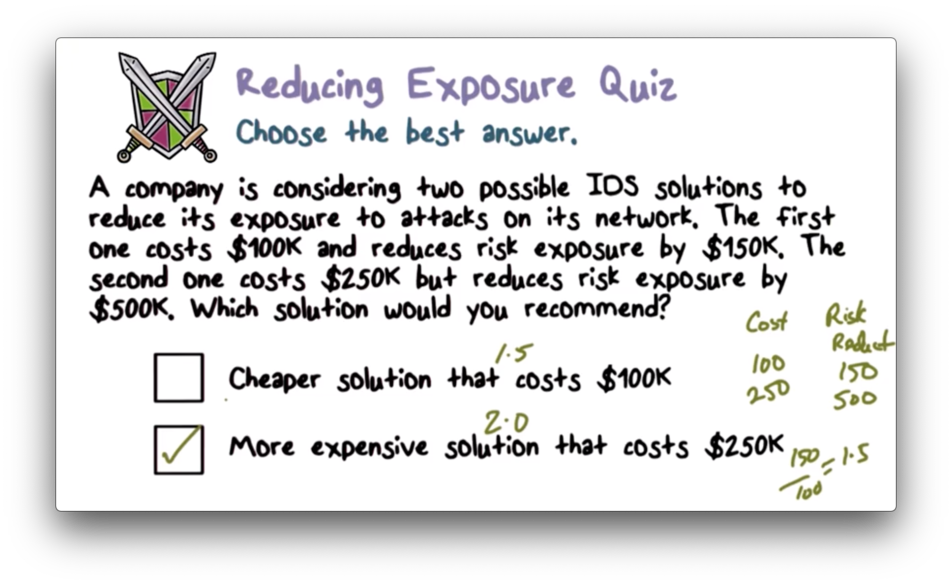

An organization wants to reduce their risk exposure, and they can achieve this reduction by implementing security controls. Since every control comes at a cost, an organization is smart to choose those controls that bring the most significant risk reduction relative to the implementation cost.

Given a pre-implementation risk pre and a post-implementation risk post and an implementation cost cost for a particular security measure, we can define risk leverage L = (pre - post) / cost.

Naturally, a business wants to choose controls that maximize their risk leverage. Any control under consideration should have a risk leverage higher than one; otherwise, the cost of the control is higher than the amount of risk it reduces.

Managing Cyber Risk

Risk assessment is a challenging exercise. A business may not fully be aware of the vulnerabilities present on their systems, and they may be ignorant of the threats seeking to compromise these systems. Without this knowledge, they can only guess at the likelihood of a successful attack.

Instead of trying to understand the probability of an attack, an organization might choose to examine the impact of an attack, which can be vast and expensive. For example, the business might suffer a loss of reputation or a decrease in sales. They may have to spend money to bring in cybersecurity firms for incident management and PR. They may incur legal costs, such as being forced to buy identity theft protection for their customers after a data breach.

After a business performs a risk assessment, they have three choices concerning managing their risk: accept it, transfer it, or reduce it.

Occasionally, a company may decide that both the probability and impact of an attack are so low that they are comfortable with the risk as is. Alternatively, a business may choose to transfer their risk by taking out an insurance policy; that way, if something bad happens, the cost is borne by someone else. Finally, an organization can reduce its risk by deploying new technology solutions, educating their employees, and providing security awareness training.

Security Breach Quiz

Security Breach Quiz Solution

Reducing Exposure Quiz

Reducing Exposure Quiz Solution

Cyber Insurance Quiz

Cyber Insurance Quiz Solution

Enterprise Cyber Security Posture Part 1

The whole point of security planning and security management is to become better prepared when it comes to cybersecurity. Cybersecurity posture captures this level of preparation; roughly, it refers to how "good" an organization is at cybersecurity. A cybersecurity posture can either be reactive or proactive.

Reactive

Unfortunately, most postures are reactive. In other words, an organization worries about cybersecurity because of some external entity or event.

In some cases, organizations have legal or regulatory requirements they must meet. If a new regulation stipulates that a particular change must be made, an organization must abide by that regulation.

Other times, an organization is merely responding to customer demands. If customers or other companies refuse to conduct business with an organization that has lax security, that organization would be wise to adjust their cybersecurity posture.

Organizations also react to adverse security events that they have suffered. A data breach, for example, can serve as an impetus to review and revise security practices.

Organizations may also react to adverse security events that others have experienced. For instance, when a bank suffers a breach, other banks may react by ensuring that the exploited vulnerabilities don't exist in their systems.

Proactive

A proactive approach to cybersecurity is best. An organization should conduct an inventory of their assets, assess their risk, plan and analyze, and implement controls that achieve risk reduction, instead of waiting for some external force.

Someone within the company should be worrying about cybersecurity full-time. This individual needs to focus on protecting assets, educating and empowering employees, drafting and maintaining security policies, and holding stakeholders accountable.

Additionally, this individual needs to have influence within the organization, as well as exposure to the highest levels of decision-making. Board-level conversations should address cybersecurity risk and investment, whether in additional personnel or technical controls. Without board-level stakeholders, this individual will struggle to accomplish their goals.

In short, this person, often a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), must be the cybersecurity champion within the organization and use their expertise and influence to position the organization to proactively mitigate cybersecurity risk.

Enterprise Cyber Security Posture Part 2

A cybersecurity champion, such as a CISO, needs to make their case to upper management to justify the security policies they want to implement. This task can be difficult for two reasons: first, risk is difficult to quantify, and, second, cybersecurity does not make money.

The primary economic argument for cybersecurity is based on return on investment (ROI), not revenue generation. For example, an investment of $5 million in cybersecurity that shields an organization from a $10 million security incident is a worthwhile spend.

Of course, demonstrating this sort of cost-benefit analysis to upper management is difficult. While a CISO would like to quantify risk and risk reduction precisely, exact numbers are notoriously hard to derive. They can present their analyses based on their experience and perception but should be prepared for other leaders to question what they perceive as unsubstantiated opinions.

Security Planning and Management

Cyber Security Budgets Quiz

Cyber Security Budgets Quiz Solution

Read more here.

Proactive Security Quiz

Proactive Security Quiz Solution

Last updated